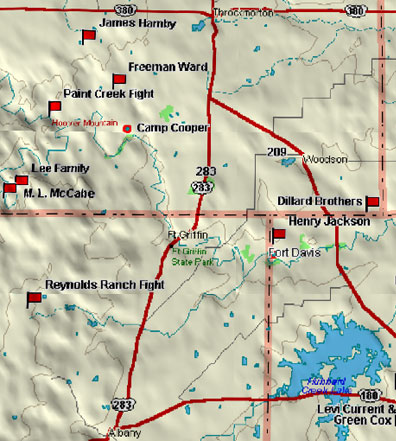

Albany | Camp Cooper | Clear Fork | Flats | Fort Davis | Fort Griffin

Early settlers to this far-flung region felt protected by the army facility at Camp Cooper. During the Civil War, emboldened Comanches and Kiowas raided the Clear Fork area several times. Families forted-up through early reconstruction and surprisingly the population grew and prospered during this time. Camp Cooper

The following story is from the book, Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman, by J. Evetts Haley.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

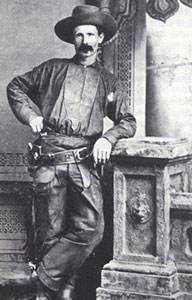

Wyatt Earp |

||

|

|

Doc Holliday |

|

In fact as well as in most movie and television versions, Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday began their legendary partnership at a saloon in the Flats when Doc gave Wyatt the goods on Johnny Reno. The Burt Lancaster/Kirk Douglas version, Gunfight at the OK Corral, had Wyatt passing Fort Griffin's Boot Hill on his way to Dodge City.

The Flats

Reynolds Company Cowboys, Frequent Visitors at the Flats

From the book, A Texas Frontier, by Ty Cashion

The following is from the book, The Frontier World of Fort Griffin, The Life and Death of a Western Town, by Charles Robinson III.

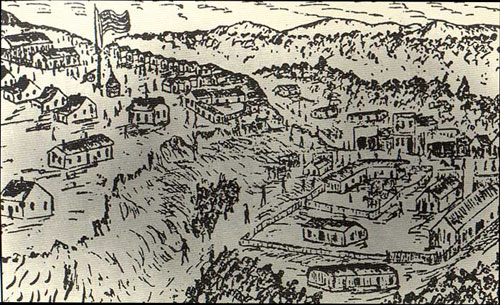

It was only natural for people to settle under the protection of the army. But it wasn't until the Indians had been permanently subdued that the town of Fort Griffin really got moving. With the plains cleared of hostile tribes, buffalo hunters were free to slaughter the great southern herd which blanketed west Texas. These people and their supporting cast-hunt outfitters, gamblers, saloonkeepers and ladies of easy virtue-were the first real settlers in Fort Griffin. They occupied a flat stretch of ground about half a mile wide, between the fort on Government Hill and the Clear Fork. Consequently, the town of Fort Griffin came to be known as the Flat. It was also called Hide Town, since the main industry was buffalo hides.

As the buffalo were hunted out, the cowboys came. The Great Western Trail ran through Fort Griffin and straight upcountry to Dodge City. For awhile, this ramshackle collection of tents and shacks on the Clear Fork was the transit center for Texas, threatening even Fort Worth.

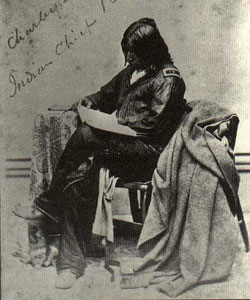

Tonkawa Chief

From the book, Panhandle Pilgrimage,

by Pauline Durrett and R.L. Robertson

From Ty Cashion's book, A Texas Frontier:

In June 1872, at an aborted peace conference near old Fort Cobb, Indian Territory, Plains Indians condemned the slaughter then taking place in Kansas. They also complained bitterly of being confined to reservations so their enemies would be safe in the tribes; former homeland. Ten Bears wryly suggested that since the government had so little success in moving the Indians, perhaps it should try "moving the Texans."

[Henry E. Alvord Report, in the "Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, H. Exec. Doc. 1, 42d Cong., 3d sess., serial set 1560, p. 389; Nye, Carbine and Lance , 135.]

...Then, shortly after 1870, technology transformed the bison into a valuable commercial resource. According to Kansas hunter J. Wright Mooar, an English firm hoping to develop a practical tanning process had requisitioned five hundred bison hides for its experiment. The plainsman proposed to a partner, Jim White, that they consign their own samples to his brother John Mooar in New York City. The perplexed commission firm that received the hides forwarded them to a storage facility amid much fanfare; as the noisome shipment plied through a curious crowd on Broadway, two venturesome Philadelphia tanners intercepted the hides. On both sides of the Atlantic leather workers soon conducted successful experiments; shortly afterward several firms announced they would purchase the commodity in volume. The big hunt had hardly begun when New England gunmakers facilitated the slaughter by providing hunters with a large-caliber rifle, the Sharps "Big 50." Out of its long, octagon-shaped barrel the twelve-to-sixteen pound gun hurled a .50-caliber lead slug from brass shells containing 110 grains of powder. A competent marksman, Mooar asserted, could fell stands of bison from "incredible distances."

[James Winford Hunt, ed., "Buffalo Days: The Chronicle of an Old Buffalo Hunter, J. Wright Mooar," Holland's: The Magazine of the South 52 (Jan. 1933): 13, 24; Don Biggers, Buffalo Guns and Barbed Wire, 8-11; Robert L. Moore, "Fort Griffin and the Buffalo Sharps," The American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin, No. 52 (April 1985).]

...As herds on the great middle range neared extinction, hunters looked for new fields. The most promising territory lay beyond the No Man's Land that formed the Oklahoma Panhandle, but the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 had designated it off limits to whites. But according to Mooar, he and another man in July 1873 crossed "the neutral strip" into the Texas Panhandle, where they encountered "a solid herd as far as we could see." All day "they opened up before us and came together again behind us." Although excited over the discovery, Kansas hunters remained apprehensive, fearing that soldiers at Fort Dodge might confiscate their teams for violating the treaty. But when Mooar, at the head of a small delegation, met with Colonel Dodge, the commander reportedly satisfied their queries by declaring, "Boys, if I were a buffalo hunter, I would hunt buffalo where the buffalo are." Texas, never a party to the Medicine Lodge Treaty, extended its blessings to the Kansans with alacrity. By the end of the year hunters and skinners were hard at work on the Southern High Plains of West Texas, creeping ever closer to the Clear Fork country.

[J. Wright Mooar, "The First Buffalo Hunting in the Panhandle," WTHAY 6 (1930): 109-11; Hunt, ed., "The Second Chapter of the Chronicle of J. Wright Mooar," Holland's, 52 (Feb. 1933): 10,44.]

...Plains Indians looked upon the slaughter with horror and resolved to turn back the whites. During the middle of 1874, however, General Philip Sheridan received authority from the Department of the Interior to "punish these Indians wherever they might be found, even to following them upon their reservations." The new policy followed the moral bankruptcy of the Grant administration. No longer could Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano sustain his peace policy against the incessant hue and cry of settlers in Texas and other states and territories contending with hostile Indians.

["Report of the Secretary of War," H. Exec. Doc. 1, 43d Cong. 2d sess., serial set 1635, pp. 28, 40.]

...Once again, during 1881 and 1882, the bison provided a final resource rush. This time, however, it was not for the hides, tongues, and meat, but for the bones that had lain bleaching in the sun for half a decade. Fertilizer plants ground them into bone meal; refineries extracted the calcium phosphate to decolor sugar; manufacturers used the ash to produce bone china; and factories used the firmest remains to fashion buttons. Even before hunters had completed the slaughter, men had freighted bones to San Antonio and Dodge City. Seldom afterward did ranch hands go to market for supplies without hauling a load.

...In January 1882, Robson noted that every day "there are ten to fifteen wagons in town loaded with bones, all bound for the railroad." end Cashion

Wagon Crossing the Clear Fork River Just Below the Flat

From the book, A Texas Frontier, by Ty CashionAs the buffalo were hunted out, the cowboys came. The Great Western Trail ran through Fort Griffin and straight upcountry to Dodge City. For awhile, this ramshackle collection of tents and shacks on the Clear Fork was the transit center for Texas, threatening even Fort Worth.

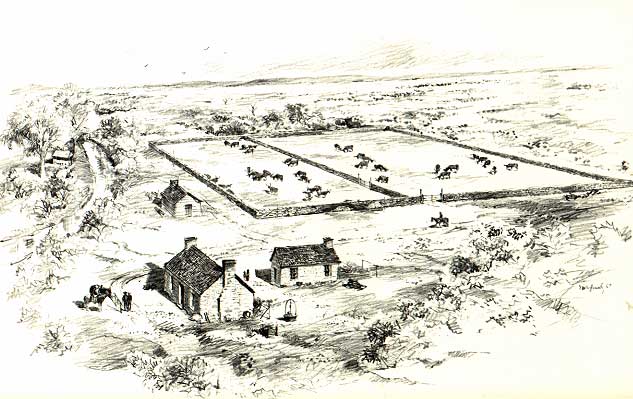

Fort Griffin, late 1870s, showing both the military post and the Flat. The large compound in the right foreground is Frank Conrad's emporium. Edgar Rye woodcut, courtesy Old Jail Art Center and Archive, Albany Texas.

The Flat ran day and night. Having a full-time population of a few hundred, offset by several thousand transient parasites, it was no place for a tenderfoot, or a man who couldn't handle himself. Nothing has yet equaled the biblical Sodom, but Fort Griffin certainly tried. If you were slick with cards or fast with a gun, the Flat was the Promised Land.

Local Merchant, "Dutch" Nance "turns dude" for a shot at a Griffin gallery.

From the book, A Texas Frontier, by Ty Cashion

This kind of environment was bound to produce some kind of side effect, generally permanent for the person affected. The trees along the Clear Fork were good and solid, strong enough to support two hundred pounds or so of dead weight at the end of a rope. And according to the old newspaper accounts, the trees were often decorated with former citizens and transients. The Clear Fork itself was sufficient to sink a body, and by the time it was found, it was so badly decomposed it couldn't be recognized. When a body doesn't have a name, there is no motive, and consequently, no suspect. The plains surrounding Griffin were wide and lonely and hid their share of secrets as well.

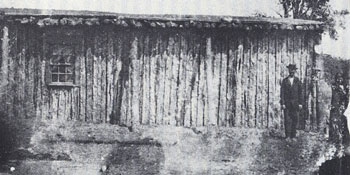

"Dutch" Nance Poses Beside His Picket-Cabin at the Flat

While a Tonkawa Indian Peers around the corner.

From the book, A Texas Frontier, by Ty Cashion

The following excerpt is from the book, Along the Texas Forts Trail by B.W. Aston and Donathan Taylor:

The town of Fort Griffin quickly grew up around the fort and became a thriving trade center, with a reputation for crime and vice not altogether undeserved. During a period of twelve years thirty-five men were publicly killed there. The historian Carl Coke Rister wrote that "the revolver settled more differences than the judge," and added that straight shooting could promote long life more than fresh air and sunshine.

Business was generally good. Buffalo hunters, rich at least for a few hours after their arrival in town, made good customers. Cowboys and cattlemen found an oasis in the Bee Hive Saloon. ("In this hive we are All Alive; good whiskey makes us funny..."). Some visited other establishments that appealed to them.

In 1876 two major events happened to Fort Griffin. The first was the arrival from Fort Richardson of Lottie Deno, riding on top of the stage with the driver. Lottie took up residence in a Clear Fork shanty. An air of mystery developed about her, as she was seldom seen except when she visited the stores for supplies, or at night when she played cards at the Bee Hive or presided over the gambling room night after night. Her seclusion had everyone speculating. Some said she was kept by a prominent married saloon keeper. One day twenty-two-year-old Johnnie Golden arrived in Griffin. As the story goes Lottie fell for him and broke off her relationship with the salon keeper. Shortly afterward Johnnie was arrested for horse stealing, but he never made it to the jail as a mob took him from the officers and killed him. Some say the saloon keeper paid $250 to dispose of Johnnie. Whatever the case, Lottie soon left Griffin, leaving the people as puzzled about her as they had been before. (Rister 1956, 135–138)

After a while they went to the little shanty where she lived and broke in to discover an elegant collection of expensive furniture and letters indicating that she had a daughter whom she secretly supported, being brought up in Boston Society.

Tonkawa Charley

Most of the tribes contributed warriors to scout for Ross' corps including Caddos and various Wichitas and even Southern Comanche. Whether it was because they were effective opponents or their reputed taste for human flesh, the tribe that most offended the Northern Comanche were the Tonkawas. Sometime after their arrival in Indian territory, an effort was made to exterminate them. The remainders, including Tonkawa Charley, escaped back across the Red River, eventually settling around the Clear Fork of the Brazos near Fort Griffin, and serving as scouts for Mackenzie's Fourth Cavalry in the final phases of the Comanche War. More

Cross Plains Road Trip

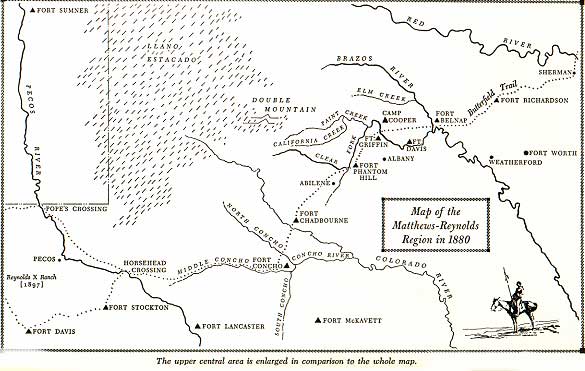

Click on the map above to activate and enlarge.

Visit Fort Griffin, Albany and Fort Phantom Hill and continue through Abilene on the Texas Fort Trail. Travel south through Forts Chadbourne and Concho into the Hill Country at Fort McKavett.

Fort Griffin

Photo from the Texas Parks and Wildlife

Daily Entrance Fees |

|

| Adult (13 and over) |

$ 2.00 |

| Child (12 and under) | No Charge |

| Seniors (Texas residents 65 on 9/1/95 or after) | $ 1.00 |

| Group School-Sponsored Trip (Entrance per person 13 and above) | $ .50 |

| Group School-Sponsored Trip (Entrance per person 12 and under) | No Charge |

Information and prices are subject to change at any time. For reservations, call 512-389-8900. Current conditions including fire bans and water levels can vary from day to day. For more details, call the park or Park Information at 800-792-1112.

Directions

To reach the park, travel 15 miles north of Albany on US Highway 283.

Tours

Groups may request tours and Living History Programs.

Photo from the Texas Parks and Wildlife

Facilities

Campsites with water, electricity and/or sewer; Primitive campground (overflow area); Picnic sites; Group picnic area; Enclosed winterized shelter (can be heated in winter and opened in summer) with tables, a grill, electricity, water, and restrooms nearby; Two group equestrian camps with water for horses only (combined capacity of 35 rigs); Trailer dump station; Interpretive center; Amphitheater; 3 miles historic hiking trails; 1.5 miles nature trails; Playgrounds with slides and swings; Restroom with showers: Texas State Park Store; Basketball court, Volleyball court; Horseshoe court, and a baseball field.

Photo from the Texas Parks and Wildlife

Activities

A portion of the official Texas Longhorn herd resides in the park. Partially restored ruins of Old Fort Griffin, including a hand-dug well, a mess hall, a ghost building, a barracks, a library, a rock chimney, a store, an administration building, a cistern, a hospital, a powder magazine, the foundation of the officers' quarters, and the first sergeant's quarters, a restored bakery, and replicas of enlisted men's huts are on a bluff overlooking the townsite of Fort Griffin and clear Fork of the Brazos River Valley (the townsite is not in the park boundaries.) Ruins of various structures still can be seen. The park offers camping, hiking, fishing, picnicking, living history, historical reenactments, and nature study.

Events

March: Longhorn Calf Branding Historic Trail Ride

April: Indian Wars Reenactment

May: Memorial Day Weekend, Cowboy Campfire Breakfast.

Fandangle

From the book, Panhandle Pilgrimage,

by Pauline Durrett and R.L. Robertson

June: Albany Fandangle

July: Night Sky Viewing

September: Labor Day Weekend, Cowboy Campfire Breakfast

Fall: Civil War Reenactment, Night Sky Viewing

December: 1870 Country Christmas

The profitability of the modern cattle business that was born in the early 50s in the Keechi Valley caused it to spread across neighboring prairies.

Ty Cashion's observations are from his book, A Texas Frontier.

...In 1865, cow hunters began probing for markets, trailing herds to distant locations over familiar paths and also blazing new ones. Early in the summer, a Dr. West and T.L. Stockton gathered beef steers from the Clear Fork range and headed for Shreveport and New Orleans, favorite outlets for East Texas ranchers even before the days of the Republic. Others followed, such as Charles Neuhaus and William G. Hoover, but turbulent social conditions soon closed that avenue. That autumn, George Reynolds, Silas Hough, and Riley St. John drove 125 head to Santa Fe. Taking a southwesterly course through Taylor County, they crossed each of the Concho's three forks before braving a dry and unforgiving stretch of desert to Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos. From there they followed the river north into New Mexico. A few months later Cross Timbers stockmen Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving-for whom the route was named-picked up this course after pushing a herd through the Clear Fork country bound for Fort Sumner, New Mexico. Visionary businessman Joseph G. McCoy opened the floodgates for all Texas cattlemen in 1867, when he convinced promoters to establish a railhead at Abilene, Kansas. Within a few years local ranchers were driving cattle to places as far away as the gold fields of California and the open plains of the Dakotas.

[Jordan, Trails to Texas, 71; Newcomb Diary, July 1-19, 1865, entry of Susan Newcomb, Jan. 4, 1867; Matthews, Interwoven, 25, 77; Webb, "Life of Phin Reynolds," 117-18; Reynolds interview; Haley, Charles Goodnight, 119; Larry Earl Adams, "Economic Development in Texas during Reconstruction, 1865-1875" (Ph.D. diss., North Texas State University, Denton, 1980), 162.]

Buffalo Camp

From the book, A Texas Frontier, by Ty Cashion

In April (1867) some of the Clear Fork herders exacted revenge against the Comanches for recent raids. T.E. Jackson, John and Mitch Anderson, Silas Hough, George and William Reynolds, and several others pursued a party of warriors to the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos near the Haskell-Stonewall County line, where they noticed a large cloud of dust kicked up by running buffalo. A closer look revealed seven Indians-actually, five Comanches, accompanied by a Hispanic man and an African American in Indian clothing-slaughtering one of the beasts. Abandoning their quarry, the warriors charged the cow hunters. One "Indian" all by emptied two six-shooters in the direction of George Reynolds, who had separated from the others. The herder dropped the warrior from his horse, however, and later killed him by breaking his neck. Another of the Comanches shot Reynolds with an arrow, its iron spike lodging in his back, where it was to remain for several years. The cattlemen soon forced the warriors into a full retreat, with Silas Hough hotly chasing the one who had wounded his friend. He soon returned with several trophies, including the Indian's scalp. In all, they had lifted the hair from five corpses and left another adversary mortally wounded.

Buffalo Hides

From the book, Panhandle Pilgrimage, by Pauline Durrett and R.L. Robertson...Governor Throckmorton had finally prevailed upon the War Department to provide relief for the Texas frontier.

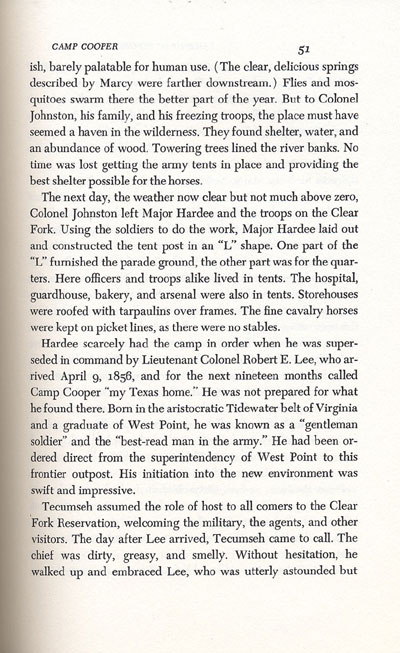

...Sheridan and Fifth Military District commander General Charles Griffin had launched a stopgap plan late in 1866 that presaged the placement of the troops that the young drover Boyd had encountered the following spring. From their makeshift base at Jacksboro the 6th Cavalry was to guard the frontier line as far as old Camp Cooper; the 4th Cavalry was assigned the area from the Colorado River to the Mexican border.

...The smartly dressed federal troops, with their shiny brass buttons and gleaming bayonets, cut an imposing spectacle to the homespun-clad herder folk. And the soldiers' self-assured march into the Clear Fork country might have seemed "as a breeze from another world," as Sallie Matthews remembered, but she was only six years old at the time. While most of the pioneers welcomed any help they could get, many among them no doubt received the troops with bated enthusiasm. After all, this force had occupied the state for two years without visiting the frontier, and only a few months earlier they had been harassing "honest white folk" in the interior. Texans also remembered that U.S. troops had maintained a presence before the Civil War, endeavoring for more than a dozen years to pacify the backcountry. When those troops surrendered their garrisons to the rebels in 1861, however, the Indians were even more of a menace than when the army had arrived.

[Matthews, Interwoven, 42.]

Buffalo Camp on the Plains

From the book, A Texas Frontier, by Ty Cashion

...Clear Fork rancher Emmett Roberts claimed that Union soldiers did little to stop Comanche and Kiowa depredations. On several occasions, in fact, warriors approached the fort itself, once venturing as close as two hundred yards. Even several years later, a Griffin commander reported that a war party had taken stock within a mile of the guardhouse, admitting also that afterward they "cleaned the valley of the Clear Fork and left for the Plains."

As Roberts suggested, small bands of Comanche and Kiowa raiders continued their minatory thrusts into the Clear Fork country. And, as before, contests between herder folk and their adversaries remained few, short, and about equal. When some cow hunters in 1869 ran twenty horseless Indians into a depression, the two sides exchanged fire; on this occasion, the raiders forced the stockmen to withdraw.

[McConnell, West Texas Frontier II , no. 645]

More fatal was an encounter near Picketville that same year. Some herders who happened upon six Comanches slaughtering a cow gave chase, cornering one of the Indians in a ravine. The brief siege ended when a knife-wielding stockman charged and killed the warrior, but not before two of the Clear Fork men fell wounded-one fatally.

[McConnell, West Texas Frontier II , no. 649]

About the same time, in the southern part of Stephens County, several Indians surprised some teamsters after their army escort abandoned them to hunt deer. The freighters bolted from the wagon and luckily escaped across a divide. Fourteen-year-old George Bishop was not as fortunate. East of Picketville, some marauders suddenly appeared, forcing him and his horse into a fallen tree. They dragged Bishop into a thicket, stuffed grass into his mouth to prevent him from calling for help, and then riddled him with arrows.

[McConnell, West Texas Frontier II , no. 653, 687]

Although home-bound pioneers had long known that moonlit nights were a particularly perilous time, cow hunters on the range could never predict when warriors might suddenly strike. Constant vigilance provided the only assurance of securing their persons and property. Routinely they hobbled their horses in different locations around camp to cut the chances of losing them all. Cow hunters never left or entered camp during the daytime, and seldom did they even remain in one location long enough to carve a path from their camps to the range. Men normally joined their herds early in the morning and did not return until after sunset, "no matter how tired we were," Roberts noted, "so that the Indians watching us could not follow." One outfit, he recalled, hid their camp so well that a raiding party almost ran a herd of horses right over the sleeping men, not realizing they were there.

[Roberts, "Frontier Experiences," 48-50, 53; Reynolds interview.]

In part because the cow hunters were so cautious, Indians seized any advantage that chance allowed. One moonlit evening in July 1872, John Hittson and eleven others were camped near present-day Ballinger. Someone awoke to discover that Indians had spirited away many of their mounts. Gathering their few remaining horses, the men headed for their headquarters, just below Shackelford County. Before noon the next day, about seventy-five Comanches attacked the herders after feigning to offer a truce. Except for the cook, who fled for his life, the party took cover behind the chuck wagon, where they resisted a day-long siege punctuated by the desperate charges of screaming warriors. Only with nightfall did the men manage to escape.

[Marshall L. Johnson, Trail Blazing: A True Story of the Struggles with Hostile Indians on the Frontier of Texas , 78-86.]

The casualties suffered by each side attested to the reluctance of* both stockmen and Indians to engage each other in pitched battles. Despite escaping with their lives, one of the herders eventually died from his wounds. The dozen or so dead and wounded warriors bought their comrades neither territory nor stock.

...B.W. Reynolds moved his wife and children to a river bend about a mile above the post because he felt that his family would be safe there. When Captain Wirt Davis toured the Clear Fork country in 1869, attempting to organize a local defense, he noted that eight or ten families still resided at Fort Davis; twelve more comprised the community of Picketville; and, eight miles west, another tiny settlement, Sand Creek, had arisen.

...By 1870, families who had persisted against the elements, Indians, and rustlers had reaped a tremendous windfall. First-comers typically reported a fivefold growth in personal wealth over the decade; no doubt they based the price of their still underreported holdings on the Texas price of beef. Matthews admitted to twenty-five thousand dollars in personal property. Even at four dollars a head this translated to 6,250 animals. Valuated at the northern Great Plains rates, his holdings had increased more than thirty times since the war began. Perhaps the ranchers themselves did not know their true net worth; between the free-running animals and wide-ranging thieves, an accurate count proved difficult. The prolific growth of the herds, however, was beyond doubt. The men at Camp Cooper, for example, who in 1865 had suffered the Indian attack that claimed the life of Freeman Ward, were reportedly tending 25,000 animals.

[U.S. Census, 1860, Buchanan, Shackelford, and Throckmorton counties; U.S. Census, 1870 , Shackelford and Stephens counties; Adams, "Economic Development," 170; Cox, Cattle Industry of Texas II , 313; Dale, Range Cattle Industry, 28-30.]

Despite accumulating small fortunes, ranching families continued to live simple, austere lives in the postwar period. Even with their operations growing to meet the size of their herds, and with others beginning to crowd them, few cattlemen bothered to purchase the land on which their livestock grazed. This de facto subsidy kept their capital outlays low. The Clear Fork's largest landholder possessed only $2,250 worth of real estate in 1870-twice as much as the second largest holder. Unlike the nouveau riche in other regions during the Gilded Age, herding folk did not build palatial mansions to herald their new-found prominence.

[U.S. Census, 1870 , Shackelford and Stephens counties.]

Beginning in 1866, the Texas Legislature required cattlemen to file bills of sale and register brands at their courthouses before trailing a herd to market. Then, in 1871, Governor E.J. Davis appointed agents in every county to regulate passing herds. Rustlers naturally found the system disruptive, but even cattlemen, upon finding that many inspectors were dishonest, became inimical to this practice and resisted the state's efforts. Owners normally agreed by mutual consent to keep brand records and settle accounts after driving cattle to market. Left to their own word, however, many hedged. Some even evaded men to whom they were indebted. Even though cattle inspectors recorded the "tallies," obligations expired after two years, and many unfortunate cattlemen went unpaid.

[Gammet, ed., Laws of Texas V , 1141-1143; VI, 1014-23; Richardson, Frontier of Northwest Texas , 262-63; Roberts, "Frontier Experiences," 51-52; Cox, Cattle Industry of Texas II , 379; J. Marvin Hunter, comp. And ed., The Trail Drivers of Texas II , 704; Haley, Goodnight , 111.]

...Barbed wire, windmills, and scientific management facilitated the boom of the early 1880s. Although grangers and small stock raisers occupied some land along the watercourses, the vast empty spaces between the streams had little utility for small operators. Large ranchers, however, acquired or leased the expansive tracts and drilled wells at costs that others found prohibitive. Fences and tanks enabled them to begin improving their stock. In 1885 a Washington official wrote a rancher, inquiring whether progress was being made toward introducing "high-bred bulls." The stockman responded: "There are but few, very few, of the old long-horn Texans in the State." Cattlemen had indeed begun specializing in all sorts of breeds. A ranch might have nothing but Durhams, like the one on Foyle Creek that "Colonel" Godwin bought from James A. Brock. Others raised Holsteins, Devons, Brahmas, and other breeds. Albany, in fact, became known as "Home of the Hereford."

[D.W. Hinkle to Joseph Nimmo, Jr., Mar. 21, 1885, in Nimmo, Range and Ranch Cattle Business , 144; Dale, Range Cattle Industry , 119-22; Frontier Echo , Aug. 6, 1879.]

...The furiously paced economic expansion continued until 1885, when conditions abruptly reversed. Texas cattle that sold in 1880 for seven dollars a head, sold for eleven dollars in 1881, sixteen dollars in 1882, and twenty-five dollars in 1883. In 1884 the market reached a plateau. Prices then plummeted, bottoming out at three dollars a head in 1885, as the first of many "die-ups" prompted stock raisers to dump their starving animals on an already glutted market. "For nine miserable years," remarked old-time chronicler Don Biggers, "it seemed that every power on Heaven and earth but turned against the cowman." The first misfortune was a series of blizzards that swept the overstocked and underwatered land. In many places cattle drifted southward until reaching the fence lines, where they piled up in a frozen mass, forming a bridge for others to walk over. When the weakened and thirsty survivors reached the rivers, they plunged into the water but could not reach the bank. Biggers commented that the Pecos in the spring of 1885 was "a revolting mess of carrion and ruin," and everywhere the country was "full of bleating, starving, motherless calves." As bad as the die-up of 1884 had been, it paled in comparison to the one that occurred during the drought of 1885-86. From the Canadian border to the Rio Grande, carcasses covered the Great Plains.

[Dale, Range Cattle Industry , 122, 125; Biggers, Buffalo Guns and Barbed Wire , 123-25, 147.]

...For twenty-three months-from June 1885 to April 1887-the sky grew stingier than anyone could remember. Ranchers, even though suffering terribly, at least found solace in seeing the range thinned of unwelcomed competitors and grangers.

...A New Yorker who visited Northwest Texas in the autumn of 1886 claimed to have counted forty-five eastbound wagons passing through Jacksboro in a single day.

[For two particularly good studies on the drought, see J.W. Williams,"A Statistical Study of the Drouth of 1885," WTHAY 21 (1945): 85-109; and W.C. Holden, "West Texas Droughts," SWHQ 32 (Oct. 1928): 103-23; Michael Thomas Kingston, ed., Texas Almanac and State Industrial Guide, 1984-85 , 345; Peter Hart, A Description of Shackelford County, State of Texas, U.S.A. , pamphlet, cited in Skaggs, Cattle-Trailing Industry , 95; Albany News, Oct. 21, 1886.]

...For over a hundred days during the growing season of 1886, Shackelford County saw nothing more than an occasional sprinkle. After a late autumn rain answered their prayers, thankful citizens offered assistance to farmers in Haskell County. At first their prideful neighbors refused relief, but two weeks later the beleaguered grangers met and declared that any act of kindness would be humbly accepted. At Hulltown, near old Mugginsville, a man wryly commented that unless it rained soon the twenty-odd members of the local Farmers Alliance might be expelled, "As none can claim to be farmers."

...Like others before them, hopeful West Texans would pour into this inviting land only to realize too late its fickle nature. The successors of Jesse Stem, Newton C. Givens, James A. Brock, and a parade of long-forgotten pioneering men and women would reap the bittersweet legacy of conquest from the alternately generous and miserly land. Through cycles of bountiful cotton harvests and plagues of boll weevils, through "gushers" and "dusters" during oil booms and busts, and through wet years and dry ones, others would come and write similar chapters of great successes and abysmal failures. Many others would come with smaller hopes and aspirations and quietly accept what the land would yield.

Fort Davis

One of the thirty tombstones in the cemetery at the site of Old Fort Davis.

Photo by Wyman Meinzer.

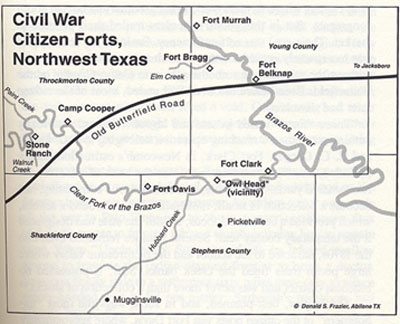

Late in 1863, the Frontier Regiment was transferred to the Confederate army by Governor Murrah. In response, the Texas Legislature declared that every man in Cook, Wise, Parker, Johnson, Bosque and McClellan counties would devote one quarter of their time in service to the Rangers. The headquarters for the northern area would be situated in Wise county at Decatur under the command of Major Quail. To the south, the Central Division, headquartered at Gatesville, would be commanded by Major Erath. Most settlers remaining west of the line forted up. Sometimes as many as one hundred families would gather in a common fort for the mutual defense of their families. North Texas forts, Blair, Buffalo Springs, Belknap and Growl, Owl's Head, Stubblefield, Mugginsville and Davis dotted the frontier.

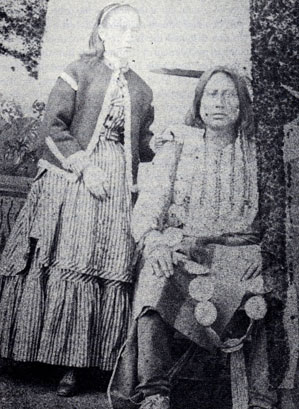

We are fortunate to have Sally Reynolds Mathews' account of the situation in the family fort from her book, Interwoven: A Pioneer Chronicle.

This Fort Davis, which is not to be confused with the old abandoned military post of that name farther west in the Davis Mountains, consisted of some thirty families. A conception of the general plan and construction of the fort is given in an item of Newcomb's diary, dated January 1, 1865.

"Fort Davis is on the east bank of the Clear Fork, and about fifteen miles below Camp Cooper. There are now about 125 persons in the fort and others are preparing to move in. There is another fort about twelve miles down the river, but it is not so large as Fort Davis. Fort Davis is 300 x 325 feet, divided into 16 lots, each lot 75 feet square, with a 25-foot alley running through the fort from east to west. This fort commenced on the 20th of October and there are now some twenty good houses here. That is, good houses of the kind. They are built with pickets, covered with dirt, and the cracks are stopped with dirt, and while not very ornamental they are very comfortable…

There was a kind, neighborly spirit of helpfulness at all times in this community. When there was sickness in a family, neighbors helped with the care of the sick one and also with the housework. When there was to be a wedding, they helped with the preparations for the festive occasion. As we had no corner store to which to go when supplies ran low, three or four men would take their teams and drive to Weatherford, a round trip of two hundred miles, and bring back supplies for all. Newcomb mentions one such trip in his diary.

"January 31 (1865)-The crowd that left here before Christmas for breadstuff returned this evening. They came in good time as there were not many rations of flour or meal in the fort when they arrived. But people could live here without bread, as there is an abundance of good beef and other meat.

Some rough country lies east of this section and it took this party well over a month to make the round trip.

There was a community milkpen on each side of the fort where the milking was done, mostly by the women. The men sat on the fence with guns to guard against a sudden attack by Indians if there had been a recent report of Indians being near. At one time, some of the men had grown somewhat lax in their sentry duty, as may be seen in the following notation by Newcomb.

"March 12 (1865)-Indian excitement has been high here today. About 9 o'clock Mr. McCarty came upon a large body of Indians about three miles from the fort. They gave him a close chase, but he reached the fort all right. The Indians were followed all day but made their escape. I think this will stir some people in this place to do their share of picketing."

(Samuel P. Newcomb was a young school teacher at Fort Davis. To reach his gravesite location, go N on Hwy 183, turn right FM Road 1481, then left CR 285 and follow the marker.)

Map from the book, Interwoven, A Pioneer Chronicle, by Sallie Reynolds Matthews.

Illustration from the book, Interwoven, A Pioneer Chronicle, by Sallie Reynolds Matthews.

From the book, Texas Rivers, by John Graves. Photo by Wyman Meinzer.

In the excerpt below, Sallie Reynolds Matthews describes her parents' initial days on the West Texas frontier:

The above story is from the book, Interwoven, A Pioneer Chronicle, by Sallie Reynolds Matthews.

Confederate Clear Fork

Ty Cashion's map and observations from the book, A Texas Frontier.

Communities and Related Links

Albany Community

Throckmorton Community

Fort Griffin State Historic Web Site

Home | Table of Contents | Forts | Road Trip Maps | Blood Trail Maps | Links | PX and Library | Contact Us | Mail Bag | Search | Intro | Upcoming Events | Reader's Road Trips Fort Tours Systems - Founded by Rick Steed |