|

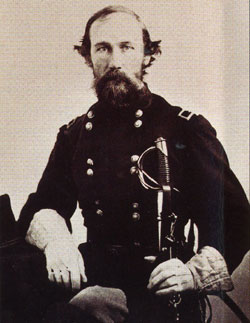

Picture from the book, Encyclopedia of Indian Wars, by Gregory F. Michno.

W.C. "Uncle Billy" Kutch at monument on the site of

the

Salt Creek Indian battle.

It is between

Jean

and Olney, about one mile north of highway.

The following story is W.C. Kutch's first-hand acount

of the Salt Creek Fight taken from the book, History of Jack County,

by Thomas F. Horton.

The local ranches were gathering cattle northwest

of Cottonwood Springs when the Indians attacked.

We spied a good-sized bunch a good way off and Shapp

Carter and I started to the bunch. When we were just about ready

to make the run we heard Henry Harrison call-we knew it meant the

Indians had run into them. We looked back to the herd which was

just about a mile from us, the Indians had rounded up the boys,

the herd and the loose cattle and were just holding them there.

Carter said to me, “What does that mean no fighting going on.”

I said to him, “I am just waiting to see which way to go.”

We were in one-half mile of the timber and one mile from them. I

said, “We can get away without any trouble.” He said,

“What sort of a tale will we tell when we get home?” Nobody

was hurt down there yet. I knew he was gritty, I had tried him before.

I said to him, “Now, Shapp, we can start to them, down there,

there are boys there that you were raised with, among them, and

it looks bad to go off, we can start and when we do some of them

will commence coming to meet us. You throw your six-shooter to the

left and I will throw mine to the right, but don’t you open

the fire.” They met us over half way, run around us, about

thirty yards from us and got in behind us but did not shoot. They

carried us from there down to where the other boys were with the

herd-we run right in to where the boys were. Lemly called out, “Rush

on to the timber right to our west” I said, “No, not one

of us will ever make it, right on the bald prairie, and fifty-seven

Indians around us.”

About three hundred yards there was a right smart

of a thicket on the side next to us, on the opposite was a bluff.

I said, “Make for that place, turn everything loose.”

That was the last resort. Some Indians were standing there who understood

everything we said and they made a run and beat us to the place.

When they got possession of that place they opened fire on us. We

had got into a little basin of a place. I told the boys to dismount

and turn everything loose that we would never need the horses any

more. All turned them loose, except a negro who was with us, his

horse was killed in a few minutes.

The fight continued from ten o’clock in the morning

till four o’clock in the evening. Will Crow was killed at the

commencement of the fight, George Lemly was wounded twice, John

Lemly was wounded twice, Rube Segress was wounded twice, Shapp Carter

was wounded twice, Jim Gray was wounded twice, I was wounded three

times, Jesse McClain was wounded once; Henry Harrison, Joe Woody

and the negro, Dick, were not wounded.

…They traveled all night in the rain and got

to us about eight o’clock the next morning. They loaded the

seven wounded men in the wagon and tied the dead man, Crow, on the

back of the wagon. There was where our real trouble set in-no roads,

the land was full of little ditches, rocks, bunches of grass, the

spikes were cutting and grinding all the time.

…We reached the ranch about twelve o’clock.

They untied the dead man from the back of the wagon and moved him

back under the wagon. I told them to get John Lemley out as quickly

as possible for he was dying. Lemley was dead when they got him

out. This was the old picket house with a dirt floor. Harmison and

all his men gave up all of their bedding and they made pallets all

around in the house to put the wounded down. I was the last one

to come into the house and there was only a corn sack for my pallet.

This man, Whitten, had pulled spikes out of Bill Peveler. I asked

him if he had any pinchers about the place. He did not. He finally

remarked, “I’ve got a pair of Colts navy six-shooter molds.”

I said, “Get them.” I told Whitten to take the molds and

pull the spikes from me. He said he could not do it. I told him

I knew better-I said, “You are the man who pulled the spikes

out of Ben Peveler that the Indians shot into him.” He said,

“Yes, but I have no tools to work with.” I told him, “You’ve

got all the tools right here that are necessary.” He wanted

me to wait till the doctors got there, I told him it might be night

before they got there and as a matter of course they will work on

the ones suffering worst, first. He finally consented to undertake

it, he put a man to each foot and each hand and A.C. Tackett to

hold my head. He cut a hole in the flesh to the bone where the arrow

went in and after hard pulling he got it out. The boys gave him

some handkerchiefs and he bound it up the best he could. I was lying

flat on the ground and an arrow had struck me in the top of the

shoulder and ran down and lodged in the bottom of my shoulder blade.

He cut a hole in my shoulder and ran the bullet molds down there

and pulled it out. The third arrow they shot into me went about

half the length of an arrow into my leg. I got that one out myself.

The doctors came about sundown. They worked on the wounded until

next morning. That day was the second after the fight. They got

an ambulance and a wagon or two and were fixing to take us all home.

We got to Flat Top Springs, three miles north of where Graham now

is and stopped for a while. Shapp Carter died there. His father

had come to us and they took him on down home that evening. They

carried us down to the old salt works, where Graham now is, after

so long a time. The balance of us got up and were ready to go. We

left part of the wounded there and left one doctor with them. Only

three were able to travel and able to be carried on home from there.

During this battle we had lost two hundred cattle,

thirty-one head of horses, the pack mule, all our bedding, our provisions,

and our ammunition was just about out when the fight ended.

The following story is from the book, The West

Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

After spending the night on Flint Creek, north of

the old Murphy Station, a group of cowmen, who were on a roundup,

waded their horses knee-deep through the luxurious wild flowers,

found so abundantly in northern Young County, and started to their

herd, approximately two miles away. It was Monday, May 16, 1869.

For several days, fresh Indian signs had been discovered. So these

cowmen realized that the approximately five hundred head of cattle,

already gathered, would attract the attention of the savages for

many miles. Consequently the Texans camped about two miles distant

from the bawling herd, to avoid, if possible, a night conflict

with the barbarous hordes of the plains.

It was a damp day. The spring breezes were blowing

intermittent flurries of rain. And about the usual hour, the cowmen

began to slowly move their cattle. Ira Graves assumed command,

and with him were: Wm. Crow, John Lemley, Geo. Lemley, C.L. (Shap)

Carter, Jason McClain, W.C. Kutch, J.W. Gray, Henry Harrison,

Rube Secris, Joe Woody, and Negro Dick, a cook.

After the herd had been drifted for about four miles,

several cattle were seen grazing in the distance. So C.L. (Shap)

Carter and W.C. Kutch were detailed to bring them in. Kutch and

Carter galloped away. They had hardly gone two miles, however,

when the two heard the shrill voices of many shouting demons behind

them. The peaceful prairies, which only a few moments before,

were waving with millions of wild flowers, seemed to have suddenly

transformed into a sea of raging red men. Carter and Kutch could

have easily escaped into the timber, but realizing the plight

of their companions, these faithful frontiersmen dashed almost

through approximately fifty-seven painted Indians, to reach their

associates, who were also rapidly riding to join Kutch and Carter.

The cowboys, only armed with cap and ball six-shooters, rushed

toward a little ravine; but when within a few yards, discovered

that it was already occupied by a large band of Indians. They

were then compelled to retreat, and assume a location in a little

depression to the right. This depression drained into one of the

prongs of Salt Creek. Their position, then, was about five miles

southeast of the present city of Olney, in Young County. Jason

McClain and J.W. Gray were already seriously wounded, and since

the little wash-out was so shallow, the dozen cowmen were forced

to lie down. It was now about ten o'clock in the morning, and

again and again the Indians' onslaughts were repulsed by the cowmen.

Wm. Crow was instantly killed during the early stages of the battle,

when a rifle ball penetrated his head; George Lemley seriously

wounded in the face, and before the fight was over, every man

received a painful wound, excepting Henry Harrison and Joe Woody.

But still the twelve citizens realized their dangerous predicament,

and waged one of the most bloody and dangerous battles ever fought

on the West Texas frontier. With one man dead, and nine others

seriously and mortally wounded, their very existence was suspended

by rotten twine. Each savage charge and onslaught came sweeping

like a death dealing tide and threatened to completely destroy

the Texans so poorly armed.

While the battle was most intense, the citizens

discovered ammunition was growing low. So the besieged cowboys

began to feel their last hopes were gone. But it was agreed the

wounded would load the guns while others did the shooting. When

the horses were shot down, their dead bodies afforded the frontiersmen

additional breastworks. After the Indians realized the citizens

were not being dislodged, they tried new tactics, which seemed

to be in accord with the command of the main chief, not in the

fight, but stationed on a nearby hill. The Indians attempted to

slip up the branch below, but when they did, five or six of their

number fell wounded.

The savages were under the immediate command of

a Negro, who seemed to inspire the Indians to fight far more desperately.

Finally, however, about five o'clock in the evening, the chief

summoned his warriors by his side, and to his place of eminence

on a nearby hill. It seems the savages were holding a council

of war preparatory to make a final drive. But just at this moment,

perhaps, the cowboys were saved by their own perseverance, and

strategy of Capt. Ira Graves, who ordered every cowboy, regardless

of whether well or wounded, to stand up and wave defiance at the

wild demons. Most every one, excepting Wm. Crow, stood up, and

this bit of strategy, no doubt, caused the Indians to think that

after fighting for six or seven hours, and after losing several

of their own number, the citizens had scarcely been harmed. And

too, during the last part of the fighting, Capt. Ira Graves and

his men had been shooting at the Indian leaders, and this apparently

caused considerable consternation in the savage ranks. So the

Indians discharged a final volley or two, and then drove the cattle

away.

When the Indians retreated, Wm. Crow had been dead

for several hours, C.L. (Shap) Carter had a severe arrow wound

in his body, and had been also painfully injured with a rifle

ball. John Lemley was mortally wounded in the abdomen with an

arrow; J.W. Gray had been twice struck with rifle balls, once

in the body and one in the leg; W.C. Kutch had two arrow heads

in his knee, and one in his shoulder; Jason McClain had been twice

wounded with arrows; Rube Secris had his mouth badly torn, and

his knee shattered; Geo. Lemley had his face badly torn, and an

arrow wound in his arm; and Ira Graves and Negro Dick were also

wounded. Henry Harrison was dispatched to the Harmison Ranch,

several miles away for aid. John Lemley died from the effects

of his wound sometime in the evening following the battle.

During the dreadful night that followed, the citizens

stood guard and waited on the wounded as best they could. The

next morning, their souls were inspired when they saw a wagon

approaching in the distance. And according to reports, A.C. Tackett,

Bob Whitten, and Theodore Miller, assisted in moving the cowboys,

and removing some of the spikes from their bodies. Messengers

were also dispatched for Dr. Getzwelder, of old Black Springs

in Palo Pinto County, and Dr. Gunn, the U.S. Army surgeon, at

Fort Richardson. But it was nearly twenty-four hours after the

fight was over, before these surgeons arrived. C.L. (Shap) Carter

died the next day after the fight, and his death made the third

victim of this battle. About two years later, Jason McClain, who

helped move a large herd of cattle over the trail, died in Kansas,

and his death was attributed to the wounds received in this battle,

which numbered among the most desperate, dangerous, and bloody

engagements ever fought on the west Texas frontier.

Note: Author personally interviewed: A.C. George,

and L.L. Tackett; John Marlin; Henry Williams; Mann Johnson;

J.B. Terrell; F.M. (Babe) Williams; Uncle Pink Brooks; A.M.

Lasater; James Wood; B.L. Ham; Mrs. H.G. Taylor; E.K. Taylor;

Mrs. Huse Bevers; Mrs. Jerry Hart; and several others who lived

on the frontier at the time.

Further Ref: History of Young Co., by Judge

P.A. Martin, as published in the Graham paper, and W.C. Kutch's

own account of this fight, as published in the Star-Telegram

and Graham paper. Clippings from these papers were furnished by

J.B. Terrell, but we are unable to supply the date.

On May 31, 1870 the Overland Stage was attacked near Salt Creek, eight miles east of the old Fort Belknap. The driver was killed and the mail was carried off. From signs of the body, evidently death was caused by bullets. The Indians were believed to have been Kiowas.

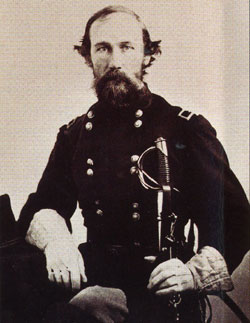

General W.T. Sherman's Tour of Inspection

The Federal authorities in Washington, who held the Whip of State, were exceedingly slow to offer necessary relief in suppressing Indian depredations along the West Texas frontier. The delay, which cost hundreds of lives of all ages, was, perhaps, partly occasioned by the constant clang of writers and citizens in the east and north who were urging more peaceful and benevolent relations with the Indians; criticizing the early frontiersman for defending their just rights. They were often charging that a great per cent or a majority of the Indian depredations were being done by outlaws and renegade whites who were disguised as Indians. Even, today, many citizens and scholars hold that view.

While the authorities and people in the east and north were urging peaceful relations with the Indians, and the establishment of more treaties, which were invariably disregarded, the savages were slaying men, women, and children along the West Texas frontier. But the pleadings and prayers of the early pioneers were continually being sent to Washington urging better protection. Finally their prayers and petitions bore fruit, but not until many citizens had been slain. Gen. Sherman made a tour of inspection for the purpose of ascertaining, if possible, the true state of affairs on the frontier. As we shall later see, Gen. Sherman's trip was made at an opportune time.

He was accompanied by Inspector General, R.B. Marcy, who conveyed the old California trail in '49, the Red River to its sources in '52, and helped survey the Indian Reservation in '54.

They reached Galveston, April 24, 1871, and four days later arrived in San Antonio, the historic old metropolis of the Southwest. While Sherman and his command passed through Boerne, then described as a town of a dozen houses, a discharged soldier, who conducted the local school, informed Gen. Sherman he was obliged to go constantly armed on account of the hostile Indians. The following day, Gen. Sherman, Gen. Marcy, and their associates reached Fredericksburg, then a town of 1000 inhabitants. May 5 they passed Mason, where a very few German families were then living. The following day, the command camped at Mendarville, then described as "A village of three houses and a small store, located one mile from the old Spanish Fort San Saba, a large structure of solid masonry." From here, the command proceeded to Fort McKavett, and reached Kickapoo Springs May 9. According to General Sherman's report, this spring was a mail station, where a picket of four soldiers was kept, and noted for Indian attacks. May 10, the command passed through Fort Concho, and then proceeded to old Fort Chadbourne which was reached two days later. From Ft. Chadbourne, the command passed through the ruins of old Fort Phantom Hill May 13, reached Ft. Griffin May 14; and old Ft. Belknap, May 16. The post was then, of course, deserted, but General Sherman ordered that a detachment of troops be sent from Ft. Richardson to these old government buildings, for Indians had been troublesome in the vicinity. May 17, they reached Ft. Richardson at Jacksboro. In describing the day's journey, the report said:

"We passed immense herds of cattle today, which are allowed to run wild upon the prairies, and they multiply very rapidly. The only attention the owners give them is to brand the calves and occasionally go out to see where they range. The remains of several ranches were observed, the occupants of which have either been killed or driven off to the more dense settlements, by the Indians. Indeed, this rich and beautiful section does not contain, today, (May 17th, 1871) as many white people as it did when I (Gen. Marcy) visited it eighteen years ago, and if the Indian marauders are not punished, the whole country seems to be in a fair way of becoming totally "depopulated."

The above story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

The following story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

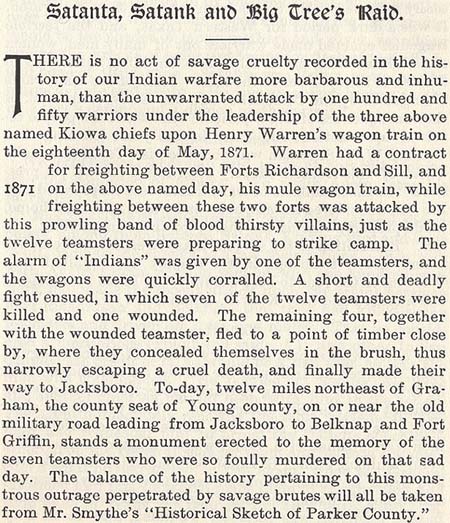

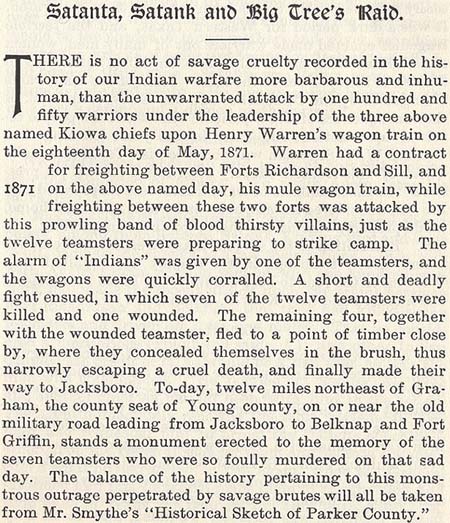

May 18, 1871, the next day after General Sherman, Gen. Marcy, and their escorts passed over the road between Fort Belknap and Fort Richardson, and two years and two days after the famous Salt Creek Fight, a wagon train, loaded with corn, and belonging to Capt. Henry Warren, who was a contractor at Ft. Griffin, was attacked by Chief Satanta, Satauk, (Satank), Big Tree, and perhaps other chiefs in command of about 100 warriors, not a great distance from Flat Top Mountain, about half-way between Fort Richardson and Fort Belknap, and on the identical road over which Gen. Sherman, Gen. Marcy and others passed during the preceding day. The train, when attacked, was under the command of Nathan S. Long, wagon-master. Many warriors were armed with the most modern rifles, known at that time. The teamsters were as helpless as children, Nathan Long, John Mullins, J.S. and Samuel Elliot, B.J. Baxter, Jesse Bowman, and James Williams, were killed. Thomas Brazeale was seriously wounded, but escaped, and R.A. Day, and Charles Brady, escaped unharmed. Samuel Elliott was burned to death. The savages chained him to the wheel of a wagon so he could not move, and then built a fire around his feet. It was difficult for Gen. Sherman, Gen. Mary and others to believe that the Indians had committed such crimes. After making a personal investigation, Col. McKenzie reported to Gen. Sherman that the report was true, as related. Thomas Brazeale, the wounded man, also found his way to Jacksboro, and related how the savage tigers from the reservation near Ft. Sill sprang upon the defenseless teamsters, killed seven of their number, one of whom was burned to death, and carried away about forty mules, as well as such other things that seemed to suit their fancy.

This example of savage butchery has often been referred to as the Monument Fight, for after it happened, Capt. Henry Warren erected a nicely painted wooden monument where the tragedy occurred. We are told that this monument decayed and disappeared many years ago.

William Tecumseh Sherman, General of the Army, traveled north on an inspection tour of the forts. He was accompanied by Inspector General Randolph B. Marcy, who had been retained by United States government twenty years prior for several explorations, including, blazing a southern route to Santa Fe, locating the head waters of the Brazos and the Red Rivers and, with Major Neighbors, establishing suitable locations for the Indian Reservations. Sherman and Marcy were accompanied by two staff members and only fifteen calvary men.

Mackenzie dispatched his Adjutant, R.G. Carter, and a detachment to intercept and escort the General and his party. This precaution was prudent, considering the 80 plus miles the party traveled between Ft. Griffin and Ft. Richardson, at its midpoint, crossed the Salt Creek Prairie, considered one of the most dangerous places on the entire United States frontier. These were the closest settlements to the Indian Territory (United States Indian Policy did not allow pursuit of the Indians onto the Reservations) so they were not only most convenient targets of short raids, but also the first and last targets of opportunity for longer raids.

Sherman gracefully declined Carter's assistance indicating an air of nonchalance which suited his political philosophy about the degree of danger presented by Indians. When Marcy pointed out to Sherman that the area was dramatically less inhabited than it was when he had passed through there twenty years prior, Sherman pointed out the houses were spaced far apart and did not indicate serious concern on the part of the builders for Indian defense.

Sherman believed a large portion of the raiders to be ex-Confederate renegades, and he had written to General J.J. Reynolds, commander of the department of Texas:

"I have seen not a trace of an Indian thus far, and only hear stories of people which indicate that what ever Indians there be, only come to Texas to steal horses... and the people within a hundred miles of the frontier ought to take precautions such as all people do against all sort of thieves... but up to this point the people manifest no fears or apprehensions, for they expose women and children singly on the road and in cabins far off from others as though they were in Illinois."

Sherman's party crossed Salt Creek unaware that they were being watched by a Kiowa raiding party of one hundred fifty warriors, led by Chiefs Satank and Satanta, accompanied by the mysterious medicine man, Maman-ti. Upon their ascension to the top of the hill, Maman-ti consulted with his owl, a symbol of death to the Kiowa. They feared even to look at an owl, which was fortunate for Maman-ti because his was only an owl skin with button eyes; he could blow air into the owl skin causing the wings to flap. He told the braves the owl warned against attacking the first target they saw, but glory would be theirs if they waited for the second. Luckily for Sherman, they saw his party first. Sometime later, traveling in the opposite direction towards Ft. Griffin, the Warren wagon train and its teamsters were the unfortunate ones.

Satanta (White Bear) blew his trumpet signaling the attack. As they charged, the drivers attempted to circle their wagons. Addo-etta (Big Tree) and Yellow Wolf cut off the lead mules, scoring the first two coups. The teamsters opened fire, wounding Red War Bonnet, a Kiowa, and killing Or-dlee, a Comanche. Big Tree shot one of the drivers out of his seat. Light-Haired-Young-Man, a Kiowa-Apache, was knocked off his horse and carried from the fight.

The warriors circled the train, their fire killing three more drivers and wounding a fourth. The remaining seven bolted through a gap in the -circling Indians and sprinted -toward the timber around Cox Mountain. Two more died as they ran and a third was injured. The Indians didn't pursue them into the timber, returning to their primary interest, the booty in the wagons. They continued circling the train, unsure of the number of defenders still remaining. An inexperienced young Kiowa, named Hautau (Gun Shot), charged a wagon. As he touched the canvas to claim it, Samuel Elliott, lying wounded inside the wagon, shot him in the face. Elliott was overtaken and chained, face down, to a wagon tongue and roasted over a slow fire.

At this time in Ft. Richardson, Sherman was receiving local citizens who related their individual accounts of the Indian atrocities they had encountered. The settlers recounted hundreds of deaths, and kidnappings in the depredations which had occurred over the last decade. Sherman was polite but unmoved, and spent the evening at a reception in his honor attended by the officers and their wives. Later that night he was awakened from his sleep and informed of the fate of the wagon train on the road he had just crossed. Now visibly moved, he ordered Mackenzie to take a detachment to investigate the report, and if true, to pursue the raiders even to the Reservation.

Mackenzie departed with four cavalry companies consisting of over two hundred men, and headed west along the Butterfield Road in a heavy rain storm. Confirming the report, Mackenzie searched to the north for over 20 days with no success. On June 4th, the detachment arrived at Ft. Sill to find the leaders of the raid in chains and Sherman already departed, continuing his inspection tour into Missouri.

A Quaker Indian agent, Lauwrie Tatum and Colonel Grierson, commander of Ft. Sill, greeted General Sherman upon his arrival at the fort on May 23. When informed about the wagon train massacre at Salt Creek, Tatum stated that Satanta's tribe was reported off the reservation and he would make inquiries, several days later when Indians picked up their rations. When asked, Satanta, in a proud statement, had not only condemned himself, but also Big Tree, Satank and Eagle Heart as accomplices.

When given the information, Sherman, lacking authority to make arrest on the reservation, asked Tatum to call the chiefs to a meeting on the porch of Colonel Grierson's home at the Fort Sill. A large number of chiefs gathered and Satanta again confirmed that it was he that had led the raid, and if anyone said different, they would be a liar. Sherman stated that Satanta, Satank, Big Tree and Eagle Heart were under arrest and would be sent to Texas to stand trial for murder, and that the Kiowa tribe would be responsible for returning the mules stolen in the raid.

Satanta then changed his story, saying he only went along to blow his bugle (signaling commands to his warriors and confusing the commands given by the army) and observe the young men learning to be warriors. Kicking Bird offered to produce a large number of mules in retribution, but pleaded that they not arrest the chiefs.

Then the shutters around the porch banged open and dozens of previously concealed soldiers brought their rifles to bear on the gathered Indians who had weapons concealed beneath their blankets. In the next few seconds, one warrior was killed and Eagle Heart escaped. The remaining three suspect chiefs were arrested and put in irons and confined awaiting their deportation to Texas.

On the morning of June 8th, Mackenzie and his troops left Ft. Sill, escorting the wagon containing the three manacled chiefs on their way to stand trial in Jacksboro. Satank told a Caddo scout "Tell my people I died beside the road. My bones will be found there. Tell my people to gather them up and carry them away." The old chief then covered his head with a blanket and began his death song.

Over the next mile he had chewed enough of his hand off to escape a manacle. With a concealed knife, he stabbed one of the guards in the wagon and grabbed a rifle but before he could fire, Corporal John B. Charlton killed him. The soldiers left his body by the road approximately where he predicted he would be, and proceeded to Jacksboro with the surviving two chiefs.

The trial was a nationwide media event, as it was the first time raiding Indians had been made to stand trial for their deeds in the community where they committed their crimes. Newspapers across the country carried headlines stating that twelve Jacksboro jurors had found them guilty of murder -and that Judge Charles Soward sentenced them to be hanged.

General/Texas Governor Edmund J. Davis

Texas State Library and Archives Commission

Governor Edmund J. Davis was ultimately pressured to overturn the sentence. He was swayed by two sound arguments, first that the Kiowa would be easier to control if there existed a possibility of the Chiefs being returned, and second that Indians feared confinement more than death. Thus, on August 2, 1871, he commuted their sentences to life imprisonment.

The chiefs were sent to the Huntsville State Penitentiary and paroled in 1873. They immediately violated their parole by leading new raids into Texas and both were eventually rearrested. Satanta died of a fall from an upper story window while in prison. Big Tree was eventually released and helped establish and became a deacon in a Baptist church in Oklahoma.

Mrs. Barbara Belding-Gibson points out in her book, Painted Pole, that the freeing of Satanta and Big Tree was a successful ploy by Lone Wolf to get them released. He represented himself to the U.S. as premier chief of the Kiowa and one who could speak for the Comanche. He insisted he would have to confer with Big Tree and Satanta before he could go to D.C. and make a treaty. The Indians were transported to St. Louis to meet with Lone Wolf then returned to Huntsville while he went to Washington. There he declared he couldn't control his young warriors without the aid of Big Tree and Satanta. If they weren't going to be released, he promised there would be open warfare. The United States representatives agreed without authority and then pressured Governor Davis to release the Indians.

The following story is from the book, Carbine & Lance, The Story of Old Fort Sill, by Colonel W.S. Nye; Copyright © 1937 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Unaware of the advent of General Sherman the Indians also were planning brilliant affairs-though of a somewhat different nature. At their camp on the North Fork of Red River, near the present site of Granite, they were sitting around the council fire passing the war pipe from one brave to another. Kiowas, Kiowa-Apaches, and Comanches were invited to participate in a great raid against the Tehannas. A hundred chiefs and lesser warriors accepted the pipe.

At this point a sinister figure emerges from the obscurity of the past. It is Do-ha-te (Medicine Man), the Owl Prophet. This Kiowa war chief and medicine man was one of the strongest personalities the tribe produced. Though scarcely known to the whites, he was the secret instigator and directing spirit of nearly every major raid made by the Kiowas in the early seventies. Known vaguely to the authorities under his real name, Maman-ti (Touching-the-Sky, or Sky-Walker), this dread personality is scarcely mentioned in written history. But today ask any old Kiowa who was the leader of the great raid in 1871, when the wagon-teamsters were killed, and the answer is, invariably, "Do-ha-te!"

If you know your history you ask, "but wasn't Satanta the leader on that raid?"

Again the reply: "Oh, Satanta. Yes, he was there. He took a leading part. But Do-ha-te was the leader."

Maman-ti was not sinister to his own people. They saw him as a person of authority and wisdom-tall, straight, kindly, and generous. Through superior intellect he could influence the tribe, and pretend to foretell events by occult means; he was relied upon to bring to a successful conclusion any warlike effort.

About the middle of May, while Sherman was riding along the Butterfield Trail, skeptical of Indian peril, this great war party led by Maman-ti rode south toward the Texas Settlements. The Indians crossed Red River between the sites of Vernon and Electra. Here at a place they call Skunk Headquarters, on account of the prevalence of skunks in the vicinity, they cached their saddles, blankets, and other unnecessary impediments. The spare horses also were left here, hobbled to prevent their straying away. A few young boys remained to guard the headquarters; the main body pushed rapidly toward the inhabited districts. Since they hoped to bring back many horses and mules, some of the men were without mounts. They rode double, or ran along holding to the tails of other animals. Extra bridles and lariats were taken along for the stock they expected to steal.

On May 17 the Indians entered Young County and headed for the Butterfield Trail, about halfway between Forts Belknap and Richardson. This was a favorite place. Sooner or later some white man would be sure to ride along the road, and the locality was remote from any town or military post.

After dark Maman-ti consulted his oracle. He sat apart on the side of a hill while the rest of the warriors crouched in silence listening for the voice of a dead ancestor. Soon it came in the cry of a hoot owl: "Hoom-hoom, hoom-hoom," several times repeated. The soft rustle of wings was heard. Then all way quiet. The medicine mad stood up, raised his arms, and, slowing intoning, interpreted the message of the owl.

"Tomorrow two parties of Tehannas will pass this way. The first will be a small party. Perhaps we could overcome it easily. Many of you will be eager to do so. But it must not be attacked. The medicine forbids. Later in the day another party will come. This one may be attacked. The attack will be successful."

At daybreak the Indians took position on a conical sandstone hill which commanded a long stretch of the stage road from where it crossed the head of the north branch of Flint Creek to a point some three miles east thereof, where it disappeared around the end of Cox Mountain. Between this hill and Cox Mountain was a broad open plain, sometimes called Salt Creek Prairie (though Salt Creek lies eight miles to the west). This field was at that time sparsely dotted with mesquite, with a few trees lining Flint Creek at the foot of the hill, and a heavier growth of scrub oak near Cox Mountain, where the timbered area begins. It was an ideal place for an ambush. The leader planned to allow the enemy to reach the middle of the plain, far from the shelter of the woods, then sweep down upon them from the hill.

Toward noon some of the scouts, who were peering through the brush on the north shoulders of the hill, saw a vehicle, preceded by a small group of mounted men, trot smartly through the trees near Flint Creek and head east across the plain. At once there was a great deal of excited whispering. The enemy were too far away to determine how strong they were. Some of the young braves wanted to attack. But the medicine man obstinately refused to permit it. Perhaps through experience or native cunning he was aware that white soldiers traveled with advance parties thrown out in front. Or maybe he had genuine faith in his powers as a prophet. At any rate the Indians allowed General Sherman (for it was Sherman's party they saw) to ride safely past, all blissfully unaware that a hundred pairs of savage eyes observed his passage.

Two or three hours passed. No other quarry appeared. Some of the young men became impatient. They had come for action, and were not getting it. They wanted to leave the band and set out for themselves. But Maman-ti held them there. Finally, toward mid-afternoon, a wagon train was seen approaching from the east. The Indians watched eagerly as ten lumbering, white-topped vehicles crawled around the north end of Cox Mountain and moved across the open plain toward them. With heels raised to prod their ponies they waited for the signal to charge.

Maman-ti waited until the wagons were in the center of the plain. Then he motioned to Satanta, who sat with a bugle in his hand. Satanta raised the instrument to give the signal. But even as it touched his lips the Indians were away at a mad gallop.

Down the slope they swept. It was a race to see who should win first coup. Second, third, and fourth coups counted also. To kill an enemy counted much. But to touch him first meant more. Several coups made a man a chief. A fast horse was a tremendous advantage. So was reckless daring.

Yellow Wolf had both. He was in the lead, closely followed by the renowned young chief, Big Tree. The rest of the horde thundered in the rear. The warriors were strung well out, with the old plugs and dismounted men toiling in the dust far behind. As the Indians emerged from the mesquite along the dry watercourse of Flint Creek the white men saw them coming. Hastily they turned off the road and began to corral their wagons.

The Indians commenced yipping shrilly and shooting off their guns at every jump. They were upon the wagon train before the corral was finished. Yellow Wolf rode between the last wagon and the others, cutting it off. The teamsters were on the ground, snatching at rifles carried in the leather boots fastened to the wagon bodies. Big Tree made a first coup. Yellow Wolf made second. Two Kiowa-Apaches were close after. Then as Yellow Wolf wheeled to the west again the firing commenced. Indians and whites were running here and there in the dust and smoke. Yellow Wolf saw a man jump off his horse and come running forward to engage in a hand-to-hand fight with the teamsters. It was Or-dlee, A Comanche. Suddenly, he dropped, shot dead. Red Warbonnet, a Kiowa chief, was wounded in the thigh. The whites were shooting "dangerously." Suddenly the Indians became wary. They pulled off and commenced whirling round and round the wagons in a yelling, shooting, pinwheel of color. Scarlet-and-white war bonnets mingled with cotton-like puffs of white smoke, yellow dust, and navy-blue loin cloths. Overhead black storm clouds were gathering across the sky. They held up the sun, whose divergent fingers reached down through gaps to touch as with a golden spotlight the fury below. It shone from polished bow, lance and carbine. It fell unheeded on desperate, frightened white men.

Three or four teamsters were killed in the first rush. The Indians did not know how many more there might be. As they rushed around and round the wagons they saw others kneeling on the grass firing from under the wagons, through the wheels. As Yellow Wolf made his second circle he saw Tson-to-goodle (Light-haired Young Man), a Kiowa-Apache, wounded in the knee. The Apache slipped from his horse and bounced in the dust. Two companions dragged him away. Several hundred yards to the west stood two women, Yo-koi-te, and another whose name is forgotten, lustily participating in the fight with shrill "tongue-rattling." Satanta may have been blowing signals on his bugle. Yellow Wolf doesn't remember. But, he says, even if the bugle had blown, no one would have paid any attention to it.

Yellow Wolf, galloping around to the east, saw a little group of white men cut out of the corral on foot and start to run towards Cox Mountain. There happened to be an opening in the savage circle on the east; they broke through it. One was shot down after running a little way. Six more kept going. Only a few Indians pursued. They thought there were plenty more whites still in the corral. Near the timber one other white was killed. The remaining five disappeared in the blackjacks. The Indians turned back; they were afraid they would lose their share of the plunder. The Indians continued to circle, watching closely. No firing was coming from the corral. Maybe it was some kind of trap. Yellow saw one of the whites, the one who had been with the last wagon, lying in the open gap between that wagon and the corral. This was the one Big Tree had killed. The one Eagle Heart killed was lying close to the corral on the north side. Yellow Wolf also saw a dead man on the ground just inside the corral. Did he kill this man? Yellow Wolf does not say. In the excitement he did not see any other bodies. The Indians were using Spencer carbines, breech-loading rifles, pistols, and bows. Most of the firearms had been purchased from Caddo George, at his "store" near Anadarko. Yellow Wolf had a gun he had captured that year from a settler in Texas.

The sky was growing darker. A big storm was coming. The Indians were anxious to finish the work and get away. But no one dared approach the wagons too soon. Some of the whites might be waiting for them.

"Keep back! It's too dangerous!" shouted the older man. "Let's get them from behind."

Hau-tau (Gun-shot) would not listen. It was his first battle, his first chance to win a point in the race for chieftainship. He ran toward the wagons. No enemy appeared. He retired a few steps in indecision. White Horse and Set-maunte, more experienced, tried to hold him back. He evaded their grasp. He rushed to another wagon, touched it.

"I claim this wagon, and all in it, as mine!" he shouted in exultation.

At that moment a wounded teamster inside the wagon lifted up the canvas sheet and shot Hau-tau full in the face. The young Kiowa fell to the ground, horribly wounded. White Horse and Set-maunte were laying their hands on the mules to claim them. They ran to pick up Hau-tau. He was still breathing. They dragged him out of the way. At this point the Indian account breaks off abruptly. Yellow Wolf declines to say more except that the Indians, enraged by the shooting of Hau-tau, proceeded to "tear up everything." After the affair was over the Indians went back to the hill from which they had started their charge, driving with them the captured mules. They placed Or-dlee, the dead Comanche, in a crevice on the south side of the hill, and piled rocks over him. Then they tied the wounded men to horses and rode north. Soon a general storm broke. The heavy rainfall turned the streams into floods. The Indians made slow progress.

No white man survived to describe the last tragic moments of the massacre. What occurred must be pieced together from the descriptions of the scene written by Mackenzie and his officers. The advance detachment of soldiers arrived before dark on May 19. The rain was still coming down in torrents. The bodies of the teamsters, swollen and bloated beyond recognition, were lying in several inches of water. The place was a litter of opened grain sacks, broken wagons, pieces of harness, arrows, and bits of cloth. Mackenzie's surgeon made the following report of what he found:

"Colonel R. S. Mackenzie,

4th Cav

Sir:

I have the honor to report that in compliance with your instructions I examined on May 19, 1871, the bodies of five citizens killed near Salt Creek by Indians on the previous day. All the bodies were riddled with bullets, covered with gashes, and the skulls crushed, evidently with an axe found bloody on the place; some of the bodies exhibited also signs of having been stabbed with arrows. One of the bodies was even more mutilated than the others, it having been found fastened with a chain to the pole of a wagon lying over a fire with the face to the ground, the tongue being cut out. Owing to the charred condition of the soft parts it was impossible to determine whether the man was burned before or after his death. The scalps of all but one were taken.

I have the honor to be, colonel, your obedient servant,

(signed) J. H. Patzki, Asst. Surgeon, U.S.A."

Mackenzie had the corpses placed in one of the wagon bodies and buried near the road. The soldiers set up two small stones over the grave, cut with seven marks to indicate the number of bodies. The grave may still be seen, a mile west of Monument School, in the field owned by Mr. James Barnett.

The floods hampered Mackenzie in his pursuit of the Indians. Furthermore he was twenty-four hours' march behind them, and the trail had been obliterated by the rain. On the twentieth Mackenzie was on the south bank of the Little Wichita, waiting for the water to subside. The Indians were farther north, crossing the Big Wichita. They made crude boats from willow branches covered with canvas. In these they placed their guns, plunder, and wounded men. They propelled the craft across the swift river by swimming on either side and pushing.

Quitan and Tomasi, Mexican-captive members of the Kiowa tribe, were great buffalo hunters. Together with two other Kiowas they lingered behind the main body to kill some buffalo, which then were running in from the west and swimming the river. They had slaughtered twelve or more, and were engaged in cutting them up when they were surprised by twenty-five men of the Fourth Cavalry under Lieutenant Peter M. Boehm. Boehm was returning to Fort Richardson after a thirty-day scout. In the sharp exchange of shots which followed, one trooper and two horses of Lieutenant Boehm's detachment were wounded. Tomasi and his horse were killed. The other Indians sprang on their ponies, mingled with the buffalo herd, and swam the river. When the main body of Indians heard the shots and saw the fugitives flying toward them they raced away. Quitan brought up the rear. The ground was soft and muddy. When the Indians stopped to catch their breath Quitan arrived, covered with mud thrown up by the flying hoofs. They gave him a big laugh and went on their way north. Boehm's men scalped Tomasi. They took the scalp to Fort Richardson, where Boehm presented it as a souvenir to the regimental adjutant, Lieutenant Carter.

Although the Kiowa raiders were burdened with the wounded Hau-tau, they moved rapidly across Red River and regained their village safely. A few days later Hau-tau died. "The screw worms got into his head," they explain. The death of Hau-tau brought the Indian fatalities to a total of three: Or-dlee, Tomasi, and Hau-tau. But the Indians were more than satisfied. They had killed seven whites, captured forty-one mules, and brought back much other plunder. They felt full of pride and importance.

The following second version of the story is from the book, Indian Depredations in Texas, by J.W. Wilbarger:

More

From Ty Cashion's book, A Texas Frontier:

Sherman ordered Colonel Mackenzie to assembly a unit to gather details and pursue the war party.

The detachment arrived at Salt Creek Prairie the next morning "in a perfect deluge of rain." The men were unable to discern the scene clearly until they came right up on the bloated corpses lying in several inches of water. The debris of the fight was scattered everywhere-"here and there a hat, an Indian gewgaw, and a plentiful supply of arrows." A soldier who observed the fallen teamsters remarked that they resembled porcupines. All of them had been "stripped, scalped, and mutilated." Some were beheaded, their brains "scooped out"; fingers, toes, and genitals of others protruded from their mouths. Those who survived the initial onslaught lived only to endure live coals heaped upon their exposed abdomens. The worst horror befell one of the men whom the soldiers found chained between two wagon wheels and "burnt to a crisp," his limbs drawn and contorted from being roasted alive. The dispatch that Mackenzie sent Sherman convinced the general that more than a half dozen years of reports pouring out of Texas were not, as he suspected, the fanciful exaggerations of grasping frontiersmen anxious to tap the federal dole.

[Carter, On the Border with Mackenzie , 81-82; Nye, Carbine and Lance, 131; M.L. Crimmins, "Camp Cooper and Fort Griffin," WTHAY 18 (1941): 42; Capps, Warren Raid, 42-54ff.]

...The most telling change was a more aggressive military policy that began to take shape following Sherman's 1871 tour of the Texas frontier. If the power of decision had been left to the general, the army would have invaded the plains forthwith, compelling the Comanches and Kiowas to choose between annihilation and surrender. While the War Department failed to get carte blanche for conducting all-out war, it was nevertheless able to scrap the primarily defensive strategy. At long last Sherman won a consensus for staging winter campaigns. The conditions, though arduous for both sides, still favored the better-equipped U.S. Army.

[Wooster, The Military and Indian Policy, 152-53; Sherman testimony, 43d Cong., 1st sess., H. Rep. 384, pp. 270-84.]

Another effective measure was combining the contiguous military departments of Texas and the Missouri. The results, however, were mixed. From old Camp Cooper in October 1871, Colonel Ranald Mackenzie led a large column of troops atop the Cap Rock, where he twice suffered the ignominy of absorbing a Comanche anabasis. The Indians' first strategic withdrawal, on October 11, netted the warriors about seventy army mounts; a little over a week later, as a blue norther whipped across the plains and canyons, the Indians created a welter of confusion in a nighttime strike that allowed their families to escape. Despite the setbacks, Mackenzie learned from his mistakes. The next year he surprised the Comanche camp of Chief Shaking Hand near the mouth of Blanco Canyon, killing more than a s score of Indians-including several women and children-taking 120 captives, and burning the lodges. With their winter stores destroyed and many of their families held under guard at Fort Concho, the first Quahadie bands surrendered at the Comanche reservation late in 1872.

[Sheridan, Record of Engagements, 5; Carter, in On the Border, 162-96ff., related his participation in the 1871 campaign and produced a detailed but sometimes suspect account. See also Hamilton, Fort Richardson, 108-19, 129-33; Richardson, Comanche Barrier, 361-65; AG, Chronological List, 49, 52.]

Negro Brit Johnson and his colorful career, during the early days, always commanded the respect and esteem of those acquainted with his activities. Brit had been reared on the frontier among the white citizens, and although he was a Negro in fact, in many respects, was not in ways.

During the latter part of January, 1871, J.B. Terrell, who still lives at Newcastle, was in Fort Worth and met Brit Johnson, who was there to try to sell his cattle to Dave Terrell. Negro Brit told Mr. J.B. Terrell that he was going to leave the following day, which was Sunday, for Fort Griffin. Brit, as a consequence, returned to Parker County, where he prepared to make his last journey.

Negro Brit was then living near old Veale Station. After loading his provisions in a bois-d'arc wagon, he started for Ft. Griffin, and was accompanied by Dennis Cureton, who was the slave of Wm. Cureton Sr. at the time of his death in 1859. Brit was also accompanied by Paint Crawford, who was a former slave of Simpson Crawford, one of the first settlers of Palo Pinto County. The three Negroes had been living on the frontier for approximately fifteen years.

Turtle Hole Battle Site from the book,

Encyclopedia of Indian Wars, by Gregory F. Michno.

About the second night out, Negro Brit Johnson, Dennis Cureton, and Paint Crawford, camped at the Turtle Hole, at the head of Flint Creek, about nine miles north of Graham, and on the north side of the road. The next morning, Indians slipped over the hill from the east, and charged the three frontier colored men. According to reports, the Indians had previously told Negro Brit they would kill him if he were ever found out alone. Negro Brit's companions ran, but Brit stood his ground and sold his life as dearly as possible. All three were killed and seventy-two empty shells found around Negro Brit's body, told the story of his bitter fight. No doubt, he made several feathered savages bite the dirt. Brit and his companions were buried near where they were killed, and on the north side of the old Fort Worth-Fort Belknap military road.

And here in an unmarked grave, at the end of his long winding trail, that led to many ranches and cow camps in western Texas, and Indian villages in Oklahoma, lie buried the bones of Negro Brit Johnson. He was a faithful friend to the whites, was highly esteemed and respected by frontier citizens, and helped write much of the early history of Young and adjoining counties.

Note: Author personally interviewed: J.B. (Blue) Terrell, who conversed with Negro Brit in Fort Worth the day before he started on his last journey, and who passed Negro Brit's grave, about the second day after he was killed; Mann Johnson; Henry Williams; F.M. (Babe) Williams; F.M. Peveler; John Marlin; Uncle Pink Brooks; Jeff (Cureton) Eddleman, who was also a slave of Wm. Cureton, mentioned above; A.M. Lasater; Walker K. Baylor, son of General John Baylor; James Wood; and many others who lived in this section of the time.

The above story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

The following second story is from the book, Carbine & Lance, The Story of Old Fort Sill, by Colonel W.S. Nye; Copyright © 1937 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The raiding season of 1871 opened unusually early. On January 24 a group of Kiowas under Maman-ti (Sky-Walker) and Quitan appeared on the Butterfield Trail two miles south of Flat Top Mountain, in Young County, Texas. Here they attacked four Negroes who were hauling supplies from Weatherford to their homes near Fort Griffin. One of these men was Brit Johnson, the hero of the Elm Creek Raid of 1864. Brit had his men kill their horses and use them as a barricade. Though the colored men defended themselves bravely, they all were killed and scalped. On their way home the playful Kiowas amused themselves by throwing the kinky-haired scalps at one another. Finally they threw them away, as the hair was too short to be of value. They had little to show for their efforts when they arrived home, but bragged about the fight nevertheless.

From Ty Cashion's book, A Texas Frontier:

Into the spring of 1871 the raids waxed in both numbers and cruelty. The worsening situation was in part a response to the overtures of a peace commission that entertained a delegation of Plains chiefs in Washington, D.C. Just as Buffalo Hump in 1845 had registered his condemnation of a similar gesture by executing a crushing raid on Mexico, his progeny now vented their wrath on Texas. Hardest hit were settlers between Forts Griffin and Richardson, due south of the raiders' reservation near Fort Sill, Indian Territory. In Young County the Indians killed four African Americans, including Britt Johnson, a "hero of the Elm Creek raid." After scalping, emasculating, and disemboweling him, they stuffed his pet dog into his abdomen. Not far from that place they attacked another man and scalped him alive. Emboldened warriors twice attacked settlers within gunshot range of Fort Richardson, and by the fifth month of 1871, Indians had killed fourteen pioneers.

[Nye, Carbine and Lance , 123-24; Allen Lee Hamilton, Sentinel of the Southern Plains: Fort Richardson on the Northwest Texas Frontier, 1866-1878 , 71; Neighbours, "Elm Creek Raid," 88-89; McConnell, Five Years a Cavalryman , 696-702; Wilbarger, Indian Depredations in Texas , 549-51.]

Other incidences where captives were retrieved by Brit Johnson.

Most army officers of the time were beneficiaries of elegant educations. Dodge's forays through the Oklahoma Cross Timbers in the early 1830s not only included his soldiers but Catlin, the artist, several natural scientists and journalists. Marcy's party fortunately included his good friend, William B. Parker, whose journal provides us with a beautifully written account of unsettled Texas.

…We were encamped in a pleasant mesquite grove, in sight of the cool spring, and though the weather was hot, a fine breeze so tempered the atmosphere that our stay was very reviving after night marches, with muddy rain-water to drink.

Whilst lying in our tents, about noon, we described some objects advancing over the brow of the hill in front of camp, and soon found them to be a party of To-wac-o-nies and Waco’s on their return from Fort Belknap.

They halted a short distance from our camp, and the women commenced putting up their temporary shelter, from sun and storm, which they constructed of boughs, skins and blankets…

The chief (an ugly old creature, a fac simile of a superannuated monkey,) soon rode up, and dismounting near his half finished lodge, threw himself upon the grass, whilst his wife-about to become a mother-stopped her work, immediately, to unbridle, unsaddle and tether his horse, for of course, he disdained the smallest labour or assistance to her.

The principal use the wild Indian makes of his wife or wives is to wait upon him, she takes his horse and attends to it when he halts, saddles, bridles and brings it up when he wishes to ride, cooks his meals, puts up the temporary lodge or shealting, and dresses what skins may be obtained in the chase, in fact, does all the manual labour necessary in their wandering life.

Her lord lounges, sleeps, drinks, smokes, eats, fights, hunts, and not unfrequently, rewards her with a sound drubbing, the only extra physical exertion he ever makes.

In the afternoon, the old chief made us a visit. He was full of affection for the whites, and showed us a certificate of character, (no doubt written by some worthless scamp, as we ascertained the old fellow to be a most arrant knave and horse-thief,) from which we learned his name to be Ak-a-quash.

He was very importunate in his begging propensities, and not at all modest in his demands, as the sequel proved.

He wanted meat, tobacco, flour, coffee and sugar, not salt meat either, for that he got at Belknap; and taking up some yellow sand in his fingers, he said, “Belknap suker so.” Meaning that he wanted white sugar; pretty well for a wild Indian, living the precarious life they do. We told him he must be satisfied with what he could get, not what he wanted, and he did not refuse what we offered him.

…In the evening the Captain, Doctor, and Major Neighbours arrived. They brought with them three Delawares and a Shawnee, the addition to our Indian force which we expected, thus making our corps of guides and hunters six strong.

Major Neighbours was a fine looking man, in the full vigor of manhood, about six feet two inches in height, with a countenance indicative of great firmness and decision of character.

He was the Indian Agent for Texas, and joined the expedition to assist in the explorations and locations, a service which his great experience and judgment peculiarly fitted him for.

The Delawares and Shawnees fraternizing so well, are often employed together on such expeditions. Another Version & More

The above story is from the book, Through Unexplored Texas, by William B. Parker.

May 20, Gen. Sherman, Gen. Marcy, and their escort, departed from Ft. Richardson and reached Ft. Sill May 23. They were visited by Lowrie Tatum, Indian agent for the Comanches and Kiowas. He reported that he had been able to accomplish but very little in civilizing his Indians, that they paid no attention to his injunctions, and continued their forays to Texas where they depredated upon the settlements. He further stated that the Indians must be made to feel the strong arm of government, a policy many people pled for long before the War between the States; and further stated that the Indians should be punished when they perpetrated their atrocities.

May 27, about four o'clock in the evening, Satanta, Satauk (Satan), Kicking Bird, Lone Wolf, Eagle Heart, and other Indians came to the reservation to draw their rations. Shortly afterwards, Satanta the Bengal tiger of the wild tribe, boasted that he and 100 warriors had made the recent attack upon the train between Ft. Richardson and Belknap, that they killed the seven teamsters, and drove away forty mules. He further said:

"If any other Indian claimed the credit of it, he would be a liar - that I am the man who commanded." Satanta then pointed out Satauk (Satank), Big Tree, and Eagle Heart, as being participants in the raid. This news was then conveyed to Gen. Sherman, who ordered the chiefs arrested and sent to Jacksboro, Texas, to be tried. Eagle Heart escaped. Satanta, Satauk (Satank), and Big Tree were arrested. When Satanta was carried before Gen. Sherman, he began to feel, perhaps, he made a mistake in confessing the crime, so he considerably changed his story. Satanta, according to reports, in substance told Gen. Sherman that he was present at the fight, but did not kill anybody himself, and that he took no part in the controversy, excepting to blow his bugle; that his young men wanted to have a little fight, and take a few white scalps; and that he was prevailed upon to go with them, merely to show how to make war. He further stated that he stood back during the engagement and merely gave directions, that sometime ago the whites had killed three of his people, and wounded four more, so this little affair made the account square; and that he was now ready to commence anew and be friendly with the whites. Gen. Sherman informed Satanta that it was a very cowardly thing for 100 warriors to attack ten poor teamsters, who did not pretend to know how to fight. He further told Satanta that if he desired to have a battle, the soldiers were ready to meet him any time. When Satanta learned that he was going to be sent to Texas and tried in the court, he said he preferred being shot on the ground. About that time, however, Kicking Bird, another chief, who was not as wicked as Satanta, arrived, and pleaded with Gen. Sherman to release the chief. When they were not released, trouble at Ft. Sill seemed imminent. In fact, some of the Indians rushed for the gates, and when they were halted by the sentinels, one of them wounded a guard with an arrow. The Indians were also told they must return the forty-one mules they had captured. June 6, following, Gen. McKenzie started overland with Satanta, Satauk (Satank), and Big Tree, for Ft. Richardson. Before they proceeded a great distance, however, Satauk, (Satank) became so desperate, he was shot.

After the chiefs were arrested and before Gen. Sherman left Ft. Sill, agent Tatum told the General that he was glad that Satanta and his associates committed the deed, and made the confession just when he did for it gave Gen. Sherman an opportunity to witness the actual conditions along the frontier. He also stated that he would have been glad if Lone Wolf had been arrested, for he is one of the boldest and most troublesome men in his tribe. Agent Tatum then stated that it had been his opinion for a year, that the Indians must be controlled by force as they had disrespected all treaties.

The above story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

The above story is from the book, Indian Depredations in Texas, by J.W. Wilbarger.

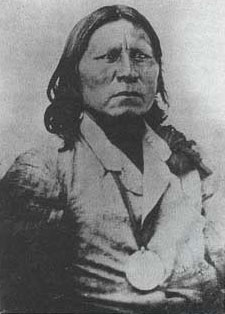

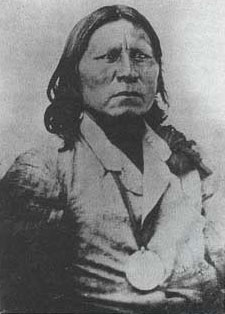

Picture of Satanta, courtesy of Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library

Satanta and Big Tree were safely carried to Fort Richardson, and there securely imprisoned in the guardhouse at the post. It was, of course, necessary to keep them under a heavy guard. The trial of Satanta began July 4, 1871. Judge Charles Seward was on the bench, and Governor S.W.T. Lanham, of Weatherford, District Attorney. The Court appointed Thomas Ball and J.A. Woolfork to represent the defendants. A severance was granted by the Court, and Satanta tried first. T.W. Williams, John Cameron, Evert Johnson, H.D. Varner, F. Cooper, Wm. Hensley, John H. Brown, Peter Lynn, Pete Hart, Daniel Brown, Lucas P. Bunch, and James Cooley constituted the jury that tried Satanta. Col. McKenzie, agent Tatum, and Thomas Brazeale, who was wounded, were important witnesses against the Indian chief. The attorneys for both the State and defense made eloquent speeches, and the trial was one of the most spectacular court proceedings ever held in the United States, and conducted in a little frontier courthouse, in a little frontier town. Jacksboro, however, just at that particular time, was enjoying considerable prosperity on account of the local military post. People traveled many miles to hear the trial, and according to reports, standing room could hardly be found in the court house. Satanta, himself, was allowed to speak, and his speech, which was interpreted, in substance, as follows:

"I cannot speak with these things upon my wrists, (Holding up his arms to the iron bracelets) I am a squaw. Has anything been heard from the Great Father? I have never been so near the Tehannas (Texans) before. I look around me and see your braves, squaws and papooses, and I have said in my heart, if I ever get back to my people I will never make war upon you. I have always been the friend of the white man, ever since I was so high, (indicating by sign the height of a boy.) My tribe has taunted me and called me a squaw because I have been the friend of the Tehannas. I am suffring now for the crimes of bad Indians - of Satauk (Satank) and Lone Wolf and Kicking Bird and Big Bow and Fast Bear and Eagle Heart, and if you will let me go I will kill the three latter with my own hand. I did not kill the Tehannas. I came down to Pease River as a big medicine man to doctor the wounds of the braves. I am a big chief among my people and have great influence among the warriors of my tribe - they know my voice and will hear my word. If you will let me go back to my people I will withdraw my warriors from Tehanna. I will let them all across the Red River and that shall be the line between us and the palefaces. I will wash out the spots of blood and make it a white land and there shall be peace, and the Tehannas may plow and drive their oxen to the banks of the river - but if you kill me it will be like a spark in the prairie - make big fire - burn heap!"

We only regret that space will not permit the publication of speeches of S.W.T. Lanham, and the other attorneys.

Satanta was given the death penalty.

The trial of Big Tree immediately followed, and he too, was punished accordingly. Upon recommendation, for fear of Indian uprising, Gov. E.J. Davis commuted their sentences to life imprisonment.

Then August 19, 1873, Gov. Davis upon recommendation of President Grant and others, paroled the Indians to their tribes. Consequently, they were escorted from Hunstville back to the reservation but their conduct was such, their paroles were soon revoked, and Satanta then returned to the penitentiary, November 8, 1874. Big Tree who also disregarded his parole, escaped, but Big Bow was sent to the penitentiary as his hostage. Concerning the conduct of Satanta and Big Tree in the Huntsville penitentiary, Col. Thomas J. Goree, the superintendent, reported as follows:

"Previous to his parole, Satanta did very little work - sometimes picking wool and pulling shucks for mattresses, but only working when inclined to do so. Since his return to the prison he has done very little work with the exception of bows and arrows. He is in bad health and suffers from rheumatism, and very often goes to the dispensary for medicine. He begs tobacco from the prisoners, visitors, and everyone he sees, very often sitting up all night chewing it. He has never worked outside the prison.

"Before parole, Big Tree worked constantly bottoming chairs, and became very expert, and could put in as many or more cane bottoms as any other hand. Big Tree was punished once, by being placed in the stocks, for being disrespectful to a guard. Satanta had never been punished. Both were very found of tobacco and whiskey. Satanta was and is very much addicted to the use of opium, and I have been informed that he has used it for fifteen or twenty years. He prefers opium to whiskey."

W.A. (Bud) Morris and Joe Bryant, of Montague County, conversed with Satanta while in the penitentiary. W.A. Morris also had several conversations with Satanta. June 19, 1878, Satanta asked Mr. Morris if he thought the government would ever release him, and when Mr. Morris replied in the negative, Satanta looked somewhat despondent. The next morning, this wild old warrior of the plains, who, perhaps, felt his case was hopeless, committed suicide by jumping from his window.

What effect, if any, did the arrest and imprisonment of these two chiefs have upon their tribes? Lawrie Tatum, the Indian agent at Ft. Sill, said:

"The effect of arresting some of the leading Kiowas and sending them to Texas to trial, has been to more effectually subdue them, than they have ever been before. On my requisition sent, they have delivered to me, forty good mules and one horse to replace the forty-one mules shot during the fight, and stolen during the Satanta raid."

He also recommended that some of the Comanche tribes, who still lived on the plains, and were unsubdued, be forced on the reservation. As long as they were there, depredating on the settlements, and encouraging the reservation Indians to do accordingly, the Indian hostilities would not cease.

The tour of General Sherman, and the subsequent arrest of Satanta and Big Tree was the beginning of the ending of Indian hostilities, along the West Texas frontier. To be sure, a few years transpired before the Indians were finally subdued. But beginning with this tour of inspection there was a radical change in government policies toward the Indians of Texas and Southwest.

Note: Author personally interviewed: Mrs. Ed. Wolfforth; B.L. Ham; Joe Fowler; James Wood; A.M. Lasater; Martin Lane; Newt Wood; W.K. Baylor; Henry Williams; Mann Johnson; W.A. Ribble; Tom Ribble; and many other early citizens who lived in Jack, Young, Palo Pinto and Parker Counties at the time. Also examined records on file in the District Clerk's office at Jacksboro.

Further Ref: Smythe's Historical register of Parker Co.; Five Years a Cavalryman, by H.H. McConnell; Lawrie Tatum's reports of the trial and arrest of the chiefs, as found in the report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1871. Also report of Gen. J.J. Reynolds, in the report of Sec'y. of War for 1871.

The above story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

|