|

Cattle ranches stretched deeper into Comanche territory and herds expanded.

Pioneer traildrivers including Loving, Slaughter and Reynolds developed

a profitable practice transporting large herds to distance markets in

Louisiana, Missouri and New Mexico.

Though livestock raids increased after the Second Cavalry relocated

to Utah, most citizens felt the confidence expressed by Mrs. Cambren

in an unmailed letter found in her Lost Valley cabin following her murder.

This letter was found in the Cambren home by Isaac Lynn, father of

Mrs. Mason: Jack County

January 12, 1858

State of Texas

Dear Brother and Sister:

I take my pen in hand tonight to address a few lines to you.

We are all well and doing well. We received your letter dated August

10, on Saturday last, it had been mislayed or we should have gotten

it sooner. We regretted it very much as you wished some advice.

But I must confess I feel some delicacy about giving it for that

which would suit us, perhaps would not suit you. As to this country,

we like it best of any we ever saw. We live about thirty miles from

where we first settled on Keechi and are living twenty-two miles

northeast of Belknap, our nearest neighbor is exactly seven miles.

I have seen only three white men since August except my family.

We have good land, good range, timber enough and good water. This

country consists of mountains, the valleys are from one to ten miles

across. The land is of grey chocolate color.

On account of the drought and late frost, we have not had a

chance to give corn a fair trial. Wheat does as well here as it

does anywhere; our wheat was cut entirely down by the frost when

it was heading. It came out and made ten bushels to the acre. I

can’t advise you to move but I think you would do well to come

here and look at the country. If we were there we could come here

and think we are doing well.

But some will say, “Oh, I know they are afraid of the Indians.”

Let me tell you I dread them no more than I do the citizens of Tyler.

They come to see us often; they are well behaved and sociable and

friendly. The wild Indians have stolen a great many horses on the

frontier, but we think they will not steal much more. There has

been a petition sent out for a thousand rangers for the frontier

but I must hurry, it is late.

I will say a few words concerning our family. We had a daughter,

born the twenty-seventh of last June. Her name was Flora Alice.

She was a beautiful child but alas, death, that cruel monster, layed

hold on her and tore her away from us. She died September the 19th,

but we do not mourn with those who have no hope, for we know we

have a child in Heaven. Dear brother, I am here alone, there is

not an individual in the land with whom I can converse except my

family. The sound of a church-going bell, these valleys and rocks

never heard or sighed at the sound of a knell or smiled when the

Sabbath appeared, but I have the Bible. I have the recollections

of the sweet gospel sermons which I had in days which are past and

gone, and better than all I have the spirit of Jesus. I often feel

happy in this heathen land, I often think I have friends that pray

for me. I ask your prayer my dear and youngest brother. I hope you

live like a soldier of the cross. I want you to bring your family

in the nurture and admonition of the Lord and if we should meet

no more on earth I hope we shall meet in Heaven.

Mr. Cambren has a remedy for his eyes and has cured the disease

but he can’t see yet how to read or write. Consequently I have

to write for him. Our family are all healthy. People in this country

are healthy. If you wish to come to this country you will come from

Tyler to Canton, from there to Birdville, from Birdville to Rockwell,

from there keep on the Belknap road to Russell’s Store, from

there to Terry’s, and from there inquire the way to our house.

When you write to Hannibell and Columbus, remember my love to them.

I can’t tell you anything about the connection here, the Jews

and Samaritans have no dealings. I have gotten no answers. I don’t

know whether you all have forgotten us, what is the matter? Hope

we will have a post office nearer soon. Direct your letters to Weatherford.

You can move to this country at any season you think best, except

the heat of summer or in the winter. We would prefer the fall. I

must come to a close. Nothing more, but remain your brother and

sister. M.C. and J.B. Cambren

On the 18th of April, 1858, the Indians came to the house of my

uncle, James B. Cambren. He was plowing in the field right close

to the house, his two oldest sons, Luther and James B., Jr., were

hoeing corn with him. Aunt Cambren called to them that dinner was

ready, Uncle said, “Wait a few minutes, it won’t take

more than twenty minutes to finish this piece and then I am done.”

About this time they looked down the road and saw some Indians coming

up from below the field. Since the Indians were still on the Reservation

they supposed they were friendly Indians. Two dismounted and jumped

over the fence to where Uncle was plowing, one shot an arrow into

his left side. It came out on his right side and he fell dead. The

other Indian shot the oldest boy dead, then shot the other boy who

was at work there. He was near the fence and got through the fence

before he died. The balance of them went into the house and took

aunt and the other children out into the yard and guarded them while

part of them robbed the house.

They then sent part of the Indians, about six or seven, over to

the house of Tom Mason about a mile away to kill and rob them. Mason

and his wife were eating dinner. Mrs. Mason looked out of the door

to where his horse was standing and said, “Tom, yonder are

the Indians coming after your horse.” He jumped up and started

to run down there. He had his six-shooter buckled on, when he got

a little way he called to his wife to bring his gun. Just before

he got to the horse the Indians shot him down. Mrs. Mason had got

near him by now and they shot her down. They had two little boys,

the youngest just beginning to walk. They did not bother the house

or the children. This bunch down at Aunt Cambren’s house robbed

the house of everything, they took her and the four children out

on a high mountain, out of sight of the place. The bunch from Mason’s

joined them there on that mountain. They had stolen some horses

the night before down on Beans Creek. They roped a wild mule and

tied it to a tree. They were fixing to tie the oldest boy they had

there on to the mule, and aunt began screaming and crying, the little

boy three years old began screaming and crying, they ran a spear

down his throat then speared him twice in the side and killed him.

They then killed Aunt Cambren, shot her three or four times. They

then tied the oldest boy, Thomas, on the mule and turned him loose.

They all put in after the mule and left there, leaving the little

girl, seven years old, and the boy two years old right there by

their dead mother and brother. The next morning they roped the mule,

took the boy off and one Indian took him up behind him.

There was an emigrant train bound for California, on the old Government

road leading from Fort Arbuckle to San Antonio, by way of Belknap.

They got their breakfast that morning, then two young men told them,

“We will take a circle out around here to the north, maybe

we’ll kill a deer. We will come to you.” They got off

about a mile and saw the Indians coming with this boy and loose

horses. They turned and rode back to the emigrant train, corralled

the wagons, got three more men and started after the Indians, leaving

the other men to guard the women and children. They got in sight

of the Indians and crowded them so close the one who had Thomas

on behind him shoved Thomas off.

He was so near dead and worn out that he dropped off to sleep.

They run the Indians quite a distance and could not overtake them

so they turned around and came back. They were talking pretty loud,

Thomas woke and saw they were white men and called to them. They

came back and got him and took him to the wagons. They doctored

him up the best they could and sent a courier to Belknap, the nearest

place, for help.

They dispatched a bunch of soldiers out from Belknap to meet and

guard them into Belknap. The little girl, Mary, and her little brother,

Dewitt, who were left on the mountain beside their dead mother and

brother remained right there until nearly sundown. Mary finally

took her brother by the hand and started to go back to the house.

She did not know which way it was, as she could not see it but luckily

she started in the right direction and soon came in sight of the

house. Then she knew which way to go. She came along right by where

her father was lying dead. She stopped and took hold of the arrow

that was shot into him, pulled it out and hid it under the fence.

She and her little brother then went into the house, closed the

door and barred it. The Indians, in robbing the house, had left

the under bed on the bedstead and one old quit. The children remained

there until the next day about three o’clock.

Old Man Lynn, father of Mrs. Mason, the next day after killing,

picked up his gun and told his wife, “I will go over and see

how Tom and Mary are getting along.” He got tolerably close

to the house and saw their two little boys there with their dead

father and mother. They had been there ever since twelve o’clock

the day before. He could see down to Uncle Cambren’s place

and saw the feathers scattered all over everything, everywhere.

He took the little boy under one arm, his gun in his other hand

and the other little boy walked. They went down to the Cambren place

and went up to the house and called but nobody answered. He started

off, went a little way and turned and went back again and called

pretty loud, “Is there any one here alive?” Little Mary

answered and said, “Me and Witt’s here.” As he came

along he had seen uncle and two boys there dead, that was why he

asked the question. When Mary answered him she got up and opened

the door. He took them to his place on Lynn Creek, the same being

named after him, and fixed them something to eat, the first they

had had since the morning before.

The next day in the afternoon some parties came along, trailing

the Indians, and found the dead people there. Some of them went

down to Old Man Lynn’s and saw that they were all alive and

got the particulars about the thing. Old Man Gage, Arch Hall and

Dan Gage were detailed from this party to stay and bury the dead.

They had lain so long they had to dig graves and put them right

where they found them. They finished burying them just after dark.

Arch Hall came to Jacksboro and on down to my place and father’s

and let us know. Old Man Gray and Medaris went with father and me

up there to the Cambren place. We got the two children from Lynn’s,

went to the Cambren house the next day and gathered up the cattle

and what household goods the Indians did not carry off and carried

them down to father’s place. There was another Indian scare

down there when we got back home. I went on after the parties and

before I got back father had taken his family and my family and

carried them to a relative’s down in Tarrant County to get

them out of reach of the Indians.

After so long a time father and I brought our families back, but

the Cambren children remained down there. The little boy that I

took away from there, with his sister, has a son living at Newcastle,

Young County, Texas, and he is a candidate for sheriff of Young

County.

The above story is from the book, History of Jack County, by

Thomas F. Horton.

Oliver Loving

Illustration by Jim Atherton

Loving led a group of local "Rangers" in pursuit of the murderers. Neighboring ranchers and their cowboys readily formed Ranger bands in

the time-honored tradition, a Ranger provided his own horse and weapons

and expected to be unpaid for risking his life.

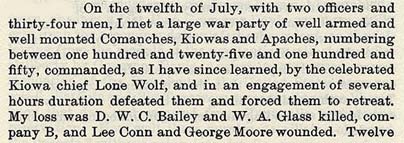

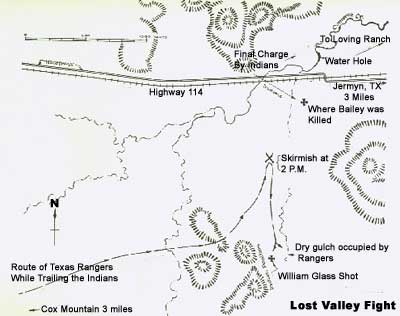

Major John B. Jones mentions the Lost Valley Massacre in his report on the victories and losses of his ranger batallion (from Indian Depredations in Texas by J.W. Wilbarger):

This account of Terrell's cowboys (Rangers) is from the book, Trails Through Archer, by Jack Loftin.

Terrell's outfit consisted of Bob Durett, Pat Sanders, Scroggins, Price Bird, George and J.B. Terrell. This same group of cowboys, along with John Profit, Henry Williams, Sam Smith and Bill York fought against the Indians near Spy Knob, Jack County, in the famous Lost Valley night fight in the spring of 1870. Ten days later they fought the Indians near Flag Springs, probably the Young County Flag Springs north of Graham.

The following story, from the book History of Jack County by Thomas F. Horton, describes another fight that happened at the same location near Spy Knob five years later.

The last Indian fight in Jack County was in Big Lost Valley in 1875. A small bunch of Indians-six in number-came a-foot, strictly on a stealing expedition. Just a few broncos and "rode-down" cow-horses were on the Loving ranch at the time, most of the boys with all the best cow-horses being out on the work. Two of the cowboys who had remained at home to take care of the work there went out in the pasture early in the morning and discovered the rail pasture fence down, knew Indians had torn it down from the peculiar manner in which Indians tore down rail fences. They looked around and soon ascertained that six head of horses had been stolen and carried away. These two men knowing that Captain Long, in command of a company of Wise County rangers, and camped at Ranger Springs a short distance away, went on down to his camp and gave him the information. It so happened that most of his men were sick (measles had broken out in his camp) but with a few men who were able for duty, came at once to the Loving ranch and soon found the trail of the Indians and gave pursuit. The Indians had gone south from the ranch, by Spy Knob, and up Cameron Creek, had stopped long enough to kill a beef and had gone on south several miles into the rough country and were leisurely riding along in single file. Captain Long and his men were very near the Indians who had not discovered the rangers till Captain Long killed one of them with his pistol. The fight followed. Captain Long killed the chief's horse and the chief killed his horse-"tit-for-tat"-the chief shot Captain Long's cartridge box, and the only damage to him was a blue knot as large as a man's fist. The rangers killed a horse one of the Indians was riding. This Indian developed to be a squaw who made every effort to surrender, making overtures to the rangers, exposing her breasts to show that she was a woman, but some of the rangers had had relatives killed by the Indians and cruelly tortured prior to this time and being in no frame of mind to extend any leniency, shot her down. The chief stayed with the squaw, but his gun jammed and he could not shoot any more. Grasping her gun by the end of the barrel, using his gun as a club he fought to the last but was killed with the squaw during the struggle. The other Indians had attempted to escape but the rangers being better mounted soon overtook all of them but one and killed them, making five Indians that were killed. The Indian that escaped was mounted on Oliver Loving, Jr.'s (son of J.C. Loving), horse, a small horse but strong and very fleet and of great endurance. Imagine, if you can, that Indian's lonely ride many miles from home, filled with remorse at the loss of all of his companions-if Indians have remorse and I suppose they like other human beings, though savage by nature have remorse and sorrow-carrying the sad news to perhaps father, mother brother, sister, of the fate that befell his companions on their last horse hunt. The squaw that was killed appeared to be beautiful, quite young and very attractive, possessing every feature of being of the white race, perhaps a half-breed, or possibly a white woman captured in early childhood, reared by the Indians, and exposed to wind and weather until very dark in complexion. However, the writer is inclined to the opinion that she was a white woman, otherwise she would not have made such strenuous efforts at surrender, something a full-blood Indian was never, in my experience, known to do.

The soldiers came out from Jacksboro, cut the heads of the Indians off and sent them to Washington to show beyond a doubt they were Indians.

The above story, from the bookThe West Texas Frontier by Joseph Carroll McConnell, gives a similar account of the 1875 Big Lost Valley fight.

After the Indians had stolen horses at the Loving Ranch, in Lost Valley, not a great distance from the present town of Jermyn, Capt. Ira Long, and his rangers, who were camped at Ranger Springs, about twelve miles west of Jacksboro, took the Indian trail, and in a short time discovered where they had killed a beef. From there, the Indians went south, toward the breaks, along Rock Creek. And when they were near the Baylor Springs, Capt. Long and his men ran on five Indians and a squaw. Before the Indians realized the rangers were around, one of their number had already been killed. A running fight followed and in a short time, another savage was shot down. They then shot the squaw and the Indian leader remained with her. Capt. Long attempted to get the chief to surrender. But when he refused, this Indian leader was killed. The fifth warrior escaped. Capt. Ira Long was wounded during the engagement, and no doubt, would have been killed had it not been for his belt.

Note: Author interviewed: Oliver Loving, Jr., son of J.C. Loving; Oliver Loving Jr. saw the dead Indian; also interviewed others.

By Eddie Matney, from the Texas Rangers Dispatch Magazine.

The early spring of 1875 began. Citizens of the northwestern frontier counties of Texas happily started to emerge from twenty years of almost constant Indian raids, killings, and thievery. Several factors had led to this sense of hope and safety.

In the year 1868, the United States government had adopted a peace plan whereby the Indian reservations would be administered by civilians. As long as the Indians stayed on the reservations, they would be protected and fed.

This act caused a real hardship on the anguished citizens of Texas and the army stationed in Texas. The Indian raiders would come off the reservations into Texas for depredations and then retreat back to the badlands of West Texas or to the sanctuary of the reservations. According to the treaty, Texas-based cavalry units chasing Indian raiding parties had to stop along the Red River and could not legally advance onto the reservation unless requested by higher authority.

Throughout the early months of 1874, the U.S. government had been seeing an ever-increasing unrest among the Indians on the reservations, especially among the Kiowa, Comanche, and Cheyenne. It was becoming apparent that civilian control was slipping. Some of the reservation Indians were leaving and going out to the Staked Plains of West Texas and others were making raids into the northwestern part of the state. It seemed that a general outbreak of Indian warfare was at hand.

Stationed at Fort Richardson in Jack County, the Army had been doing its best to protect the homesteaders and ranchers, but the number of cavalry companies was never enough to give proper protection of such a large area. Through patrols, the soldiers found and had several fights with warriors, yet the Indian raids continued.

The raids coming out of the western parts of the state, especially from the reservations in the Oklahoma Territory, were so numerous the citizens were begging the state government for extra protection. In answer to the pleas, the state legislature authorized Governor Coke in 1874 to organize six companies of Rangers for deployment across the west and northwestern frontier counties of the state. They were to be designated as Companies A through F and were to have full legal power to arrest “wrong doers” and especially to find and either kill or drive out Indian raiding parties. This contingent of men was to be known as the Frontier Battalion.

Overall command of the Frontier Battalion was placed under John B. Jones, a Civil War veteran, and he was given the rank of major. Major Jones reported to State Adjutant General William Steele.

G.W. Stevens of Wise County was commissioned captain and authorized to recruit men from the Wise County area for the new Company B, stationed west of Wise County. Enlistment was to be for one year or less. Stevens was the captain of a Wise County minuteman company and had always answered the call of neighbors to lead in chases and fights with Indians. In the last two or three years, he had been wounded in the hand and the hip in a fight with Indians just above Buffalo Springs, located in Clay County.

Stevens recruited to the full compliment of seventy-five men. Several of the enlistees had lived in Wise County for years and had experience fighting with Indians. Company B moved out to the western part of Young County for duty. By early June, the unit was on station and riding on patrol over Young, Archer, and Jack Counties.

The men soon got their first baptism of fire. On July 9, 1874, Corporal Newman and eight men were attacked by about 50 Indians while patrolling in western Archer County. The engagement lasted about four hours, with no lives lost on either side.

After organizing the battalion, Major Jones had begun his first series of inspection tours up the line of his units in order to position the companies where he thought they would do the most good. He also set about whipping the battalion into the proper fighting force that he desired. At each company, he would take five or six men to provide an escort for protection as he traveled the dangerous frontier counties.

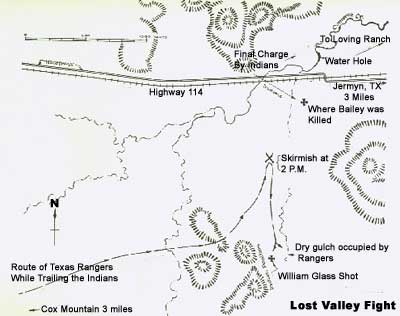

While visiting with Company B on July 12, 1874, Major Jones, his escorts, and a portion of Company B had a major fight with approximately 125 Kiowa and Comanche Indians in Lost Valley, about sixteen miles west of Fort Richardson. The fight lasted for several hours and there were casualties on both sides.

Recognizing that the Grant Peace Policy was a failure, the Army was finally authorized in late July to hunt down and drive into the reservations any Indians, wherever found. The Army then set in motion a devastating five-pronged attack throughout the west and northwestern part of Texas and the southwestern area of the Indian Territory. This became known as the Red River War.

After several months of fighting and unrelenting tracking by the Army, almost all the pursued Indians began to see that their old way of life was gone. They started to come back to the reservations and surrender.

In November, Adjutant General Steele informed Major Jones that the Frontier Battalion could not be sustained at its present level because the state treasury was low on cash flow. Steele, wishing to keep the battalion in force, cut the manpower of five companies in half, leaving each company with thirty Rangers commanded by one 1st lieutenant.

Captain Stevens of Company B left the Ranger service with an honorable discharge and returned to his home in Decatur. In turn, 2nd Lieutenant Ira Long was promoted and placed in command of the company.

By the spring of 1875, the Red River War was over and the northwestern part of Texas was, for once, almost free of Indian raids and depredations on its citizens.

While the Army had been chasing the Indians, Company B had continued their patrols against the occasional horse-stealing party slipping across the Red River. Early May of 1875 found the little company of Rangers camped in the foothills just east of Lost Valley at a spring then known as Raines Spring. Location of the camp was three miles east of the present community of Jermyn, just north of present State Road 199.

On May 5, 1875, Major Jones rode into the camp of Company B with his escort. He was perhaps surprised to find that the men there had a measles outbreak. The next day, after conferring with Lieutenant Long about the condition of the company and the Indian situation, Jones wrote a report to Adjutant General Steele:

Sir

I have the honor to report my arrival at this the camp of Co B yesterday. I find the measles in camp. Seven or eight men just recovering but not able for duty, six more down, and new cases breaking out every day. Consequently the Company is, and has been for several weeks, entirely unfit for service, and will not be able to do any scouting before the expiration of their time of service.

I regret this much more, because the Indians have visited this immediate section three or four times already since the first of January, and will probably come frequently during the Spring and Summer. They have stolen horses twice this spring from Mr Loving whose ranch is five miles from this place.

I have eleven men with me, some of whom have not had the measles, and have established a quarantine between my camp and Leuit Long’s.

Loving (James C. Loving) was a rancher who, in 1868, had moved his headquarters and ranching operations from Palo Pinto County up to the northwestern end of Lost Valley, located on the western edge of Jack County. Lost Valley was an area of flat land approximately three miles wide and about eight miles long, north to south. It was somewhat surrounded by rocky hills and low mountains and made for an excellent place for raising cattle and horses. The northern end of the valley was watered by two creeks, Cameron and Stewart.

For several years, the Loving ranch had been almost constantly harassed by Indian raiding parties who either killed or stole the cattle and horses—especially Loving’s horses. Two of Loving’s cowboys, Mr. Wright and Mr. Heath, had been killed by Indians in the last two years.

Perhaps on the very day that Major Jones arrived at Lieutenant Long’s campsite, a party of six Kiowa men and one squaw slipped away from their reservation in the Indian Territory for a short raid across the river into Texas. Arriving in the Lost Valley area on the night of May 7, they headed to Loving’s ranch. There they stole some horses out of the corral and rode southwest down Cameron Creek.

The next morning, after Loving and his men had left for the day’s work on the ranch, two of the men who had stayed at the ranch house soon discovered that part of the fence was down and a few of the saddle horses kept in the corral were missing. Knowing that there was a Ranger company stationed southeast at Raines Spring, the boys saddled their horses and quickly rode to give the alert to the Rangers.

Once informed, Major Jones gathered some of his men and rode towards the ranch to investigate the theft. When he arrived, he found the messengers to be correct.

Following the trail south along Cameron Creek, the Ranger force lost the tracks left by the raiders and began a search along the western area of Lost Valley. Finally, several miles south of the ranch house, the Indians trail was found just north of Cox Mountain at the south end of the valley.

Following the trail and riding at a fast rate, the Rangers overtook the raiding party close to Rock Creek, northeast of the present community of Bryson. One of the Indians was shot and killed immediately. A running gunfight then took place in which four more of the raiders were killed. Two Indians were able to make their escape. With the chase and fight over, the Rangers returned to their camp at Raines Spring.

The next day, May 9, Major Jones sent a Western Union telegram from Jacksboro to Adjutant General Steele in Austin:

With small detachment of my command I struck Indian trail in Lost Valley yesterday. Overtook them & killed five only one known to have escaped. One of my men slightly wounded. Lt. Long’s horse killed another wounded Indians blankets marked U.S.I.D.

As a follow-up, Major Jones wrote a report to Steele, giving a description of the fight:

Headquarters Frontier Battalion

Camp near Lost Valley Jack Co. Texas

May 9th 1875

Gen Wm Steele

Adjt Genl

Austin.

Sir,

I have the honor to report that information reached me yesterday morning about ten o-clock that some horses had been stolen from Mr. Lovings ranch, some five miles distance, the night before. I immediately started to the ranch accompanied by Dr. Nicholson, the Surgeon, Lt Long and ten men of Company B, five men of Company A and four men of Company D.

From the ranch we searched through the western part of the valley; found some Indian sign, but no trail until we reached the south end of the valley, five or six miles from the ranch, when we struck a trail just where I entered the same valley last summer when in pursuit of Lone Wolf and his party.

We followed the trail at a brisk gallop in a southeasterly direction three or four miles, when we overtook a party of seven Indians. Luit Long killed on the first fire.

Then they took to flight and a running fight ensued for five or six miles in the woods and over rough and rocky hills and hollows, during which they changed their course and performed almost a complete circle, so that the fight ended within a mile of where we first struck their trail. We killed five; the other two evaded us in the woods and made their escape into the mountains.

Private L.C. Garvey of Co. B received a very slight wound. Lt. Long’s horse was killed and two horses wounded. No other casualties on our side.

The Indians were armed with breach loading shot guns, and six shooters and fought desperately, three of them continuing to fight after they were shot down. One of those killed was a squaw, but handled her six-shooter quite as dexterously as did the bucks. Another was a half-breed or quarter, spoke broken English, was quite fare and had auburn hair.

They were well mounted, but had no horses but what they were riding. Four of those were killed in the fight. Some of them proved to be horses that were stolen from Mr. Loving about three weeks ago, the others were taken night before last. It is very evident that they had mounted themselves at the first ranch they came to, with the design of penetrating farther into the settlements, as there course lay in the exact direction of Keeche valley in the northeast corner of Palo Pinto, and northwest corner of Parker County, and if we had not overtaken them, would doubtless have reached the settlements yesterday evening.

The fight took place in Jack County, about fifteen miles a little south of west from Jacksboro, on the head of rock creek. They were well clothed, and doubtless directly from the Reservation, as their blankets were marked U.S.I.D. One of them had the scalp of a white woman fastened to his shield.

In this report, Major Jones went on to give special commendation to Lieutenant Long for his leadership, coolness, and courage in the fight. Lieutenant Long (later captain) penned a very interesting story of his part in the fight:

We found some sigh at the ranch but no definite trail until we got about six miles south in the valley. Watching closely in order not to lose it and by any chance let them escape again, I sighted far ahead and saw a man standing under a tree. The very fact that he was alone roused my suspicions and speaking to the Major about it we turned our field-glasses on him and he ran into the timber. I hurried to investigate and when I reached the tree, was so intent on examining the footprints that I neither looked up, nor around, until I heard my men shout, ”Indians!” and saw them turn in the direction that they had discovered them. Jumping my horse, which was a fine one, I was off at a dead run. Getting closer I saw there was but seven in the bunch. Outdistancing my men I gave them a hot chase for about three miles, pouring hot lead into them as I ran. The men overtaking me used their ammunition freely, as did the Major, with telling effect. I saw that one of the scoundrels had it in for me and I dodged more than one of his bullets. But seeing him draw his horse closer and draw a bead on me I let him have it between the eyes and when he doubled up and fell I resolved that I would come back that way and strip him of paraphernalia for he wore the trappings of a chief.

Bullets were whizzing constantly around us, but we were doing some pretty fair shooting ourselves and seeing my shot had taken the horse from the chief I felt like we could at least report progress.

I could not tell whether he was wounded or not, but he was shielding himself in the brush and trying to pick off my men one at a time, making every shot tell. It seemed to me the very next one took my horse in the center of the forehead and when I felt him tremble I knew that it had done its hellish work.

When I hit the ground I was on my feet. Here came the old painted devil straight toward me, yelling and shooting like mad. I had emptied my pistol and having to reload gave him the advantage. But with a round in place I fed him melted bullets until both his and my guns were empty. Then it dawned on me in a flash that it was a game of tit for tat between us. I recall how thankful I was that I was big and brawny and strong and then we closed. I had never then, nor have I since, seen such strength and agility as that Indian possessed. When I threw him off in a grapple he bounced like a rubber ball. And he used his gunstock as skillfully as I did mine.”

My men had gone on with the remainder of the bunch, and we were both tired out. I knew I could expect no help from them, and that it was the best man for it. He was panting for breath, so was I, and I knew that neither of us could hold out much longer when, plunk! A shot took him in the knee. One of my company, fearing that I was in trouble, had ridden back, and taking in the situation, risking a bullet, although he said afterward he ‘didn’t know whether it would take me or the chief, for it was nip and tuck as to who would be on top next.’ That gave me a chance to reload my pistol and at such close range I felt like the ball I put into him did the work. But I didn’t take time to see, for sure. Jumping a horse, I was off with my rescuer to try my hand on the rest of them. We got three of them after that and on the way back we went to see if the old chief was dead, and there he lay stretched full length.

The state would have Indian troubles in the far western section of Texas for several more years. However, the raiding party of May 8, 1875, proved to be the last in the northwestern frontier counties.

The following story is from the book, The Men Who Wear the Star, by Charles M. Robinson, III. Over the last decade, this young historian has authored engaging and informative works dealing with this region's history including Bad Hand, Satanta and The Men Who Wear The Star. It is because of the exceptional readability of his piece covering this famous fight that it is offered here.

Jones, with an escort of about twenty-five men, arrived at the headquarters of Capt. G.W. Stevens's Company B, at the old Ranger post of Fort Murrah, on June 10. The following day he ordered the entire company to move about ten miles east to Salt Creek, where the grass and water were better. There they received word that a band of Comanches had attacked and killed a cowboy named Heath at Oliver Loving's corral, and tracks were plainly visible.

Gui-tain, nephew of Chief Lone Wolf

(Photo from the book, Carbine & Lance, The Story of Old Fort Sill, by Colonel W. S. Nye; Copyright © 1937 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The next morning Jones sent a scouting detail consisting of two men from his own escort along with two from Stevens's company under the command of Lt. Tom Wilson. They reported a large trail heading southeast, out toward the dangerous Salt Creek Prairie. Jones broke camp immediately, taking Stevens, Wilson, and thirty-three members of the battalion to follow the trail. The group also probably included several volunteers drawn from Loving's cowboys. Unknown to the Rangers, however, this was not the trail of the Comanches who had hit Loving's corral-it belonged to a much larger party of about fifty Kiowas, including some of that nation's greatest warriors. It was a murder raid, organized by Paramount Chief Lone Wolf to avenge the deaths of his favorite son and nephew, both killed the year before in a fight with federal cavalry in south Texas. The party was led by Maman-ti, the wily and gifted medicine man responsible for the most successful Kiowa raids. Before leaving the Indian Territory, Maman-ti had consulted his oracles and predicted a successful expedition in which at least one white would die without any losses to the Kiowas. None of the warriors had any reason to doubt him.

The Salt Creek Prairie, isolated but well traveled, had always been good raiding ground for the Kiowas. Almost as soon as they came out onto the prairie, they jumped four cowboys, but the cowboys, mounted on fresh horses, escaped; the Kiowa ponies, exhausted by the long trip from Oklahoma, were unable to keep up. The failure to take the cowboys, along with the incredible, windswept loneliness of the prairie, discouraged some of the younger warriors. Sitting on a hill overlooking the valley, they began muttering among themselves, and Lone Wolf gave them a dressing-down.

"Don't be scared," he commanded. "If any Texans come and chase us, don't be afraid. Be brave. Let's try and kill some of them. That's what we came here for."

At that moment, one warrior spotted the glint of the sun on metal off in the distance, a sign more whites were coming. Maman-ti led them along the ridge where they could get a better view and saw a large party of well-armed men, all wearing white hats.

The Rangers had already followed the trail some fifteen miles. Now it was very fresh, and they estimated at least fifty warriors. They found where the Indians had stopped to water their horses, and where they had killed and roasted some cattle. They rode past the rough monument that soldiers had erected over the mass grave of the teamsters massacred during Sherman's 1871 visit, and but lost the trail as it led into rough and rocky ground approaching the hill. Some of the younger, more inexperienced men rode ahead to find it again.

As the Rangers continued into Lost Valley, expecting to see the Indians ahead on the open plain, the Kiowas backtracked, crossing the Ranger trail and circling around above them, keeping under the cover of the hills. Maman-ti had worked out a trap. He concealed most of the Kiowas in a gorge in the hills, then he and another warrior rode down into the valley and dismounted to lead their horses where they would be in plain view. Spotting them, Jones led his men straight into the snare as the other warriors charged out from among the boulders and mesquite thickets. The major held his men together as the Indians circled. Ranger Lee Corn received a gunshot wound that broke his shoulder and nearly took off his arm. Separated from the rest, he managed to crawl into the brush and hide. Another Ranger named Wheeler stayed with him and helped bandage the arm. Most of the Rangers were caught in the open, and Stevens told Jones, "Major, we will have to get to cover somewhere or all be killed."

Jones ordered a charge that broke through the Indian line, and the Rangers managed to get into a thicket in a gully but were cut off from water. Several had lost their horses in the charge, and Ranger George Moore had a flesh wound in the lower leg. William "Billy" Glass was shot down and left for dead. The Indians, Jones noted, "are all well armed with improved breech loading guns (they used no arrows in the fight) all well mounted, and painted, and deck [sic] out in gay and fantastic style." There was no question in his mind that they were out for blood.

The two sides began sniping at each other, with Billy Glass lying out on the plain between them. Terrified of what would happen if he was captured alive, he called out, "Don't let them get me. Won't some of you fellows help?" The Rangers responded with a heavy covering fire while three men dashed out and brought him in.

The Indians were making trouble along a ridge to the rear, and Rangers William Lewis and Walter Robertson volunteered to hold that position while the others held the front. Jones took them to find the best spot, and as they settled down he told them, "Boys, stay here until they get you or until the fight is over."

Later, during a lull in the shooting, Lieutenant Wilson went to see how they were doing. He was sitting under a tree fanning himself with his hat and describing the Kiowas in the strongest Anglo-Saxon terms when Lewis said, "Lieutenant you ought not to swear like that. Don't you know that you might be killed at any minute?"

"That is just so, boys," Wilson agreed and became quiet. A few minutes later, a Kiowa bullet cut a limb overhead, bringing it down on the lieutenant's bare head. As the blood poured down, he momentarily thought he had been shot. A later examination of the tree showed it had been shot to pieces on the side facing the Indians.

The Kiowas, meanwhile, were settling down for a siege. In a murder raid, the purpose was enemy scalps with no losses to their own side, and they were taking no unnecessary chances. The day was hot and the Rangers were about a mile from the nearest water. The Indians decided to wait them out. None of their own had been hurt. The wounded whites were calling for water, but Jones had forbidden anyone to try to reach the creek. Finally, as the sun began to go down and the firing slacked, Ranger Mel Porter said, "I'm going for water, if I get killed."

"And I'm with you," David Bailey replied.

They mounted and dashed for the creek. The others could see Bailey sitting on his horse by the bank keeping lookout while Porter filled the canteens. Suddenly, about twenty-five Indians moved in on them. The Rangers in the gully tried to signal by firing their guns, and Bailey shouted for Porter to flee. The two men took off in different directions.

Porter was caught by two warriors near the water hole. Keeping his nerve, he fired at them until his pistol was empty, then threw it at one of the warriors. Using his lance, the warrior levered Porter off his horse, but before he could kill him, firing from the injured Lee Corn and Wheeler drove off the two Indians. They were content to take Porter's horse, while the Ranger dove into the creek and swam underwater until he came up by Corn and Wheeler. They stayed together until after dark, when they made their way to Loving's ranch. Bailey was cut off, surrounded, and levered off his horse with a lance. Lone Wolf himself chopped his head to pieces with his brass hatchet-pipe, then disemboweled him.

The Kiowas were satisfied. They had killed at least one Ranger (actually two, because Billy Glass had died), and they began to leave. The badly mauled Rangers tied Glass's body to a horse and rode back to Loving's ranch. The Kiowas did not admit to any losses, although Jones claimed at least three had been killed. Glass was buried at Loving's ranch. About 3 A.M. the next day, they returned to Lost Valley under cover of darkness and recovered Bailey's horribly mutilated body. At sunup, a detachment of cavalry arrived from Fort Richardson, and the Rangers and soldiers spent the rest of the day looking for the Indian trail before the Rangers returned to camp.

Continuing his inspection tour after the Lost Valley fight, Jones came to Camp Eureka on the Big Wichita River, where he found Capt. E.F. Ikard's Company C "too far out to render the most effect service" and ordered it into closer proximity to Stevens, so the two companies could come together in an emergency. Meanwhile, scouting parties from both Ikard's and Stevens's companies were in the field, keeping pressure on the Indians, and a party from Company C had actually raided a camp and captured forty-three horses and mules, some of which were claimed by citizens from whom they had been stolen.

From Ty Cashion's book, A Texas Frontier:

...in the spring of 1874, the legislature created the Frontier Battalion, composed of Texas Rangers. Its services, combined with those of federal troops and a small army of buffalo hunters, placed irresistible pressure on the Comanches and Kiowas. Just before the force took the field, war parties had roamed the Clear Fork country seemingly at will. In February they had stolen stock within a mile of Fort Griffin and had stripped the horses from settlers attending a revival at Picketville. By the end of the year, however, Indian depredations had all but ceased, and the Texas Rangers claimed no small part in the improved conditions.

|