McIntire's Early Days in Texas

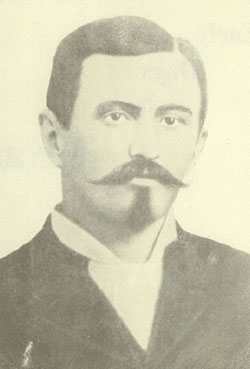

Jim McIntire

Photo from the Western History Collections,

University of Oklahoma Library

The following is from the book, Early Days in Texas, by Jim McIntire.

CHAPTER II

How I Became a Cowboy

...

Southern Ohio was a great chicken-fighting country at that time, and the sport is not dead there yet. When I was at home, I had nothing to do, and I liked to see the chickens perform with the spurs on. Well, to make a long story short, I got to fighting chickens as regularly as some people "shoot the can." I was always on the lookout for a rooster that could fight and picked up some pretty good ones. Every night mill-men, nail-makers, and corner-loafers, to the number of forty or fifty, would assemble in the basement of a grocery, and the fun would begin. Betting was never very heavy, as shinplasters were in circulation then, and amounts were small as compared with amounts wagered in the twentieth century. My father learned of my adventures with the birds and gave me a scolding that I shall never forget.

About this time I had developed an ambition to be a cowboy and see life on the plains as portrayed by the dime novels I had been reading. I could not get over my father's scolding, and as another boy, whose name was Cash Denny, had ambitions along the same line, we ran away from home together. Denny is at present the proprietor of two prosperous meat markets in Denison, Texas. We first went to New Orleans, but did not stop there long, as we were anxious to get into the cow country.

From New Orleans we went up the Red River to Shreveport, Louisiana, and from there walked along with some bull teams to the place where Dallas, Texas, now stands. Dallas was but a straggling village then. There were only a few houses, a mere

17

trading-point for the cattlemen. There wasn't a railroad nor a fence in the whole State of Texas, and we were where our cowpunching ambitions could be gratified. We were not overburdened with baggage, as Cash could easily take care of his one extra shirt, while I had only an extra pair of pants to look after. I had all the money, which consisted of a two-dollar bill. We were not much worried over our finances, but when I found a roll of shinplasters which contained three dollars and fifty cents, we were full of enthusiasm. Our enthusiasm led us to purchase a link of Bologna sausage and start for Ft. Worth. At the time we reached Ft. Worth the town consisted of one house. Old Man Terrel lived there and kept a feed-yard, where we secured lodgings for the night The next morning found us on our way to Weatherford. As we were coming into the Indian country, we began to feel just a little nervous at times. Whenever we came to a creek, we would pull out our little four-barreled pistols and investigate. We were very cautious, as we had read in our yellow books how cautious Indian-fighters were. When night overtook us, we found a house which was inhabited by an old gray-haired man and woman. They were of the old rebel sort and wouldn't let

us stay all night, because we were from the North. It was hard to have to pull out and "hit" the plains for the night, and as we were awful hungry, as boys will sometimes become under similar conditions, I shot one of the old man's young pigs, which got in the way of my pistol. We built a fire and were preparing to hold a high carnival over the roast pig, when the old man set his bulldog on us. As we did not care to have the dog make a supper off of us, we ran away, leaving the pig on the fire. We did not care to pass up the old man's generous hospitality entirely, so, after it was good and dark, we crept back and registered for a night's lodging in the haystack. We were hungry and tired all at once, and could have thoroughly appreciated a nice warm meal at home. While we were thinking over our misfortunes, a noise on the outside of the stack startled us. We thought of the Indians, our hair assumed a Pompadour aspect. However, we got our

18

guns ready, and, on peering out, saw that it was a man. We spoke to him, and he answered in a white man's voice, which sort of acted as a safety-valve on our throbbing hearts. It turned out to be a humpbacked peddler, and we were so glad that it wasn't an Indian that we welcomed him to share our castle.

We were two hungry boys when we awoke next morning, but not any hungrier than the peddler who shared the haystack with us. We didn't stop to prepare much of a toilet, but set out early for Weatherford, the peddler accompanying us. His pack was heavy and his stomach light. He grumbled continuously, which did not do much toward making things cheerful. We trudged along, however, determined to make Weatherford by night. We had not traveled far until we found a big new dishpan which had fallen from a passing wagon. We carried this along, hoping that we would find an opportunity or two for using it. A few miles farther on the opportunity came, for as we were passing a grove we noticed a company of negroes preparing breakfast after having spent the night in the grove. We could think of nothing but how hungry we were, and the bacon the negroes were broiling smelled awfully good. We made them a proposition to trade our dishpan for some bacon and corn bread, and, as dish-pans were valuable assets on the frontier of Texas, we had no trouble in reaching an agreement. With a fairly good supply of corn bread and bacon under our belts, we "hit" the road for Weatherford again. After tramping all day without anything further in the way of food disturbing our stomachs, we landed in Weatherford about dark, a little more tired and a little more homesick than when we registered at the strawstack. We cut loose from the peddler and went to the old Blackwell Hotel, where we got supper and a good bed. The Blackwell Hotel was a two-dollar house and we had only a two-dollar bill between us, but we put up a bold front and did not allow such little things as becoming stranded to worry us. However, we were so tired that we went to bed soon after supper. We got up early the next morning and started out to look for work. I ran into J.C. Loving, a

19

stock man, who was hiring all the men he could get to protect the cattle on his ranch from the depredations of the Indians. I struck him for a job for myself and companion, and, as we were

likely-looking youngsters, he hired us. We went back to the hotel in high spirits over our good luck, especially as the work was right in line with the yellow-backed novels we had read back in Ohio. After settling up with the landlord, we joined Loving for a trip to the ranch.

The Indians were pretty bad at that time, and their boldness in committing depredations was alarming. There were all kinds of stories floating around the town about how the Indians were attacking the ranches and killing and burning as they went. These stories were not exaggerated either, for on one occasion they rode into Weatherford and drove off all the horses hitched to the court-house hitching-rack in the center of the town. This little incident of frontier life had happened just a few days before our arrival in Weatherford, and was a sample of what we could expect in the future.

Loving's ranch was in the Big Loss Valley in Jack County, where the Indians were the worst. After he had hired all the men he could pick up, we started for the ranch. There were about thirty-five men in the party, and with a large number of horses and several supply-wagons we started out in true Texas frontier style. The journey to the ranch was made without incident, except while we were passing through Jacksboro we saw two dead men lying on the sidewalk who had been killed in a dance-hall row the night before. The scene was too much for our "tender-foot" hearts, and we would gladly have exchanged the adventures of ranch life for the comforts of home. But there was no turning back now, and we kept our places in the procession until we arrived at the ranch about the middle of the afternoon.

CHAPTER III

Life on the Ranch

Loving's ranch, which was to be the scene of many exciting adventures, was about twenty miles long and ten miles wide, occupying the entire Big Loss Valley. The valley was surrounded on all sides with wooded hills and lonesome peaks, and the afternoon our eyes first rested upon it, the cattle and buffalo were grazing contentedly in the distance, making as beautiful a scene as could be found in the whole State of Texas. The peaceful appearance was but an illusion, however, as the Indians were too plentiful to keep still long at a time. Away to the right lay the ranch buildings, corral, etc. The buildings were situated on Clear Creek, whose branches watered the valley. Clear Creek derived its name from the clear water which flowed between its banks, and was the home of the finest black bass I ever saw. The buildings were built by driving posts into the ground so close together that they made stockade houses, and consisted of Mr. Loving's residence, the ranch quarters, and a smokehouse. The houses were roofed with bark and were made as comfortable as possible for the facilities at hand.

We were now right in the heart of the Indian country, surrounded by hostile Kiowas and Commanches. We took to ranch work all right, and for a month everything went well. We were always on the lookout, however, and traveled in groups. We were constantly hearing of Indian depredations, and often found signs showing where they had passed in the night. Loving's ranch was the outpost of civilization, and was the first ranch the Indians had to pass in going from the Reservation to the settlements.

March 17, 1869, was the day for a general round-up, and a number of cow-punchers came over from Jacksboro to help out. They camped just across the creek, about two hundred yards from the ranch, and prepared to eat dinner before starting on the big cow-hunt. Our horses were grazing close to the camp, and I was in the house with the rest of our boys, eating dinner, when a shot was fired from behind the corral. Thirty-five Indians had crept up and taken positions behind the corral. In an instant everything

was excitement and everybody trying to get a line on the Indians. On the ranch firing a shot was the recognized signal that Indians were approaching, and the Jacksboro boys immediately leaped to their saddles. The Indians had anticipated this move on the part of the cow-punchers, and held their guns aimed at the saddles. John Heath was the first one to reach his horse, and had just placed one foot in the stirrup when he went down, hit by a Spencer bullet which entered the head just over the left eye. The horses then broke for the ranch corral. Here it was that I got my first taste of Indian fighting, and I plunged into the thickest of it. When the horses started for the corral, we were making it warm for the Indians, and succeeded in holding them at bay. One Indian, however, started for the horses in the attempt to prevent them from entering the corral. Loving saw his game and started after him, and succeeded in turning the horses into the corral. It was a thrilling sight to see Loving and the Indian race for the horses, exchanging shot for shot. After each shot they would wait a few seconds, watching each other intently, to determine if the other was hit. By this time we had beaten the other Indians back, and they were off in a bunch. We then turned our attention to the duel between Loving and the lone red man, but, as it was a fair fight, neither one having an advantage, we did not interfere. Finally the Indian wheeled his horse around and galloped up the creek to where we had a fine big saddle-horse hobbled. As he drew near the horse he threw his lasso, and at the same time whipping out his knife, cut the hobbles as he was passing. This was all done while riding at full gallop, and under the fire of thirty-five guns. Having captured the horse, he joined the rest of the Indians. The Indians, baffled in their first attempt, again drew closer and opened fire. Mrs. White, Loving's sister-in-law, loaded guns for me, and I took a position under a big oak tree in the yard, firing at the approaching Indians as fast as she could load the guns. Inside the house there was a large gun-rack, which was kept filled with loaded guns for use in the Indian raids, and had these in reserve, so I could keep shooting as fast as I could

take aim and fire. Bullets were flying thick and fast around me, as the greater part of their fire was directed at me and Mr. Loving, who was between the Indians and the corral where all the horses were. All the rest were mounted and had to load their own guns, so it fell to me to do the most of the firing, as Mrs. White was an adept at loading. The Indians tried hard to hit us, knowing that if they had Loving and me out of the way, they could cut the rest off from the corral and sweep down and capture the horses. We were fighting at from two hundred to five hundred yards, and our Henry and Spencer rifles were not very effective at that range, as it was impossible to shoot with any degree of accuracy. The coolest one of the whole party was Mrs. White, who loaded guns and handed them out to me just as if that were her regular business. Her three little children were in the house, but not even a thought of the danger they were in affected their nerves. At last all but two Indians had withdrawn from the fight, and they were sitting on their horses near the corral where they shot Heath. Mrs. White thought they might be dislodged by a big old-fashioned foreign-made gun which shot a very large bullet. She handed this out to me saying, "Here is a big gun; try them two setting on their horses." I laid down, taking careful aim, and fired high. When I fired, one of the horses jumped, and the Indian, slapping his horses's side, wheeled and galloped away, patting his back at me. It was really amusing, and Mrs. White "gave me the merry ha! ha!" as they would call it in Kansas City. She laughed good and hard. I don't know whether it was at me or the Indian, but I never saw her laugh so heartily in time of peace.

When the last Indian had gone, we took an inventory of the fight, and found that it had lasted about half an hour and we had one man fatally wounded. The Indians succeeded in getting their wounded away with them, so we could never tell how much damage we inflicted. A laughable incident occurred in the first part of the fight, when a little colored boy the Jacksboro boys had brought over to cook for them started for the supply-wagon to get

his gun. a big fellow named Henson, in a spirit of fun, grabbed the little black urchin and held him up between himself and the Indians. How that boy did squeal! The boys all thought the Indians had hit him and insisted on Henson letting him go, as it was a hard matter to fight with a little "n-----" squealing fit to kill and no time to stop and laugh.

The boys lost no time in caring for John Heath, who was still alive. They carried him to the ranch, a distance of two hundred and fifty yards, where they tenderly laid him down. The brains were oozing out of the wound in the forehead, and it could be seen at a glance that he was not long for this world. He was unconscious and life quickly ebbed away. The boys dug a grave, wrapped the body in blankets, and consigned it to Mother Earth. On top of the body was placed a lot of sticks, as boards were unheard of on Texas ranches in the sixties, and the earth was thrown in on top of the sticks.

The boys were then divided into two squads, one of which started in pursuit of the Indians and the other was left to guard the ranch. It fell to my lot to remain at the ranch. I climbed the big oak tree under which I had a half-hour before poured a hot fire into the ranks of the Indians, and acted as a lookout. From this position I had a full view of the entire valley. The Indians did not come back, however, and we spent the time quietly watching until the other party returned. Late in the evening the boys came in, leading a white horse covered with blood. They had followed the Indians up into the mountains to the northwest of the ranch, where they came upon the horse, which belonged to the Indians. Where the horse was captured there was blood all over the rocks, but no Indian could be found. The horse was a fine animal, and he was named "Whiteman."

After the excitement of the Indian raid died away, everything at the ranch ran smoothly for some time. One evening a Mexican by the name of Lorenzo and a fellow-rancher named White went to the upper end of the valley to drive the cattle out

of the timber, so they would not become mixed with the wild cattle which ran there. The two separated to hunt up the cattle, and in due time the Mexican returned, but White failed to show up. White was riding a racing pony and should have been back at least as soon as the Mexican, so the boys suspected foul play. The next morning we took the Mexican to the place where they separated. From there we followed White's trail for a distance of two miles. We found where White had ridden up to within fifty feet of a bunch of seven Indians, who were hidden behind a small hill. The trail showed where he had wheeled his horse and broke for the Big Rocky Mountains. The length of the strides also showed that he was just "hitting the high places." He must have been outrunning the Indians, as he left the mountains and turned toward the ranch. Then the Indians split and ran in the shape of a letter V. White had a good horse, and this fact must have made him careless, as his horse fell in a ditch, allowing the Indians to overtake him. They killed and scalped him, cut all the leather off his saddle, and took the saddle-tree and his horse. I picked up a large and very fine ostrich plume, which had been lost by one of the Indians. White had lain in the sun all day, and decomposition had already set in. We brought the body in to the ranch and buried him beside Heath. These were two funerals at which few tears were shed, but all the boys' hearts were full of sorrow just the same, and the tenderness and respect shown for the dead was just as marked as I have ever seen anywhere.

A few days after the tragic ending of White we had occasion to get the cattle out of the timber again. Four of us were in the party, and it was a drizzling, rainy day. We saw an object in the timber some distance away which looked like a bunch of cattle, and we started for them. When we were about a mile from them, one of the boys yelled: "Boys, that is not cattle!" But we kept on, and soon discovered that what we took for a bunch of cattle was in reality a band of Indians, mounted, but leaning over their horses' necks in order to make their forms as difficult to distinguish as possible. They were about one hundred yards out from the timber and watching our movements carefully. There was a creek about a quarter of a mile from the point where the Indians were, which was bounded on each side by high bluffs, with a nice little valley stretching away towards the ranch. We kept right on until we got under the bluff, out of sight of the Indians, when we cut loose for the ranch as fast as our horses could travel. When we had ridden about a half-mile, we pulled up and looked back. As the Indians were not aware of the fact that we had discovered their presence and played a little trick upon them, they made a charge on the bluff at the point where they expected us to come out. As near as we could count, there were thirty of them, and we watered our horses while watching them make the charge. As soon as they discovered they had been tricked, they started after us, but we were a mile away before they got a good start. They waved at us to come back, and we stopped our horses to allow them a breathing-spell. They then fired a few shots at us and started again, but we thought discretion the better part of valor, and galloped home.

This band of Indians made away with twenty-three head of Loving's horses one night, but were not satisfied with that, as they stayed in the vicinity until they got over one hundred good horses.

Indians always go on a raid when the moon is full, and we could expect them just as regularly as the moon got full. We would take extra precautions, but they came in such numbers and so stealthily that they generally got away with something. So the next full moon came around, and another band of Indians with it. We had all the horses, guarding them along the pasture fence when the Indians came. The night was very dark and cloudy, and it required all the vigilance the men were capable of to protect the horses grazing under their charge. Six men were detailed for this duty, and they divided the time into three watches, with two men on watch at a time. When Pat Sweeney and his partner were

on watch, two Indians sneaked into the pasture and "swiped" a few horses. They located the boys and the main bunch of horses, and planned to get between the horses and the fence and stampede them. Sweeney's eagle eye spied them, and, although it was too dark to distinguish their figures, he was sure they were Indians. Riding up, he commanded them to halt, threatening to fire if they made another move. They kept on toward him and he opened fire on them. At the first shot the Indians wheeled their horses and started toward the ranch, with Sweeney and his men right after them. We heard the noise and ran out to head them off, but it was so dark we could not tell our boys from the Indians, and didn't dare shoot, although Sweeney kept yelling for us to do so. The Indians saw the ranch and turned off up the creek. They were on fresh horses they had stolen from the pasture, and galloped up the creek at breakneck speed. A couple of hundred yards from the ranch the Indians rode over a bluff, falling about thirty feet, and we gave up the chase for the night. There was a quantity of broken rock at the bottom of the precipice, and we expected to find Indians, horses and all, either killed or badly hurt. The next morning we examined the place where they went over, but the only thing to show where they lit was a little horse-hair on one of the stones. It was a miracle how they escaped.

The next night we drove the horses into the corral, knowing the Indians were still in the vicinity. That night we could hear them roaming over the prairie hooting like owls. Knute White, Loving's brother-in-law, had a favorite horse, which he was afraid the Indians would get, and in order to keep it out of their reach, he tied it to the corner of the house. There was a big rail-fence around the house, and one Indian, a little more bold than the rest, crept up top the fence, and hid himself on the inside. White was laying for any attempt of the Indians to get his horse, and armed with a double-barreled shot gun, loaded with buck-shot, and a six-shooter, he stood guard. Along in the night the Indian came out from his hiding place beside the fence and crawled up, untied the horse, and, leaping on his back, galloped

off. White was so taken by surprise that he forgot all about his double-barreled shotgun, and began shooting after the fleeing Indian with his six-shooter. It is needless to remark that the Indian got away with the pet horse, and White was very much chagrined."

CHAPTER IV

Indian Atrocities

In those days the buffalo would occasionally come down into the valley in immense herds, and when they left, large numbers of cattle mixed up with them would be forced to go along. Curtis Brothers, of Jacksboro, had many cattle on the range with Mr. Loving's herds, and when the cattle would wander away in this way, they would furnish a number of men to go with Mr. Loving 's men to separate them from the buffalo herds. Getting cattle out of a herd of buffaloes is exciting sport, and we enjoyed it better than anything in the way of ranch work. It was a grand sight to see the prairies black with buffalo almost as far as one could see. There were also wild horses and all kinds of game on the prairies, which added zest to the work. Our party had been out about two weeks and succeeded in reclaiming about two thousand cattle from the buffaloes. We shot game and had a good time in general. In fact, we did so much shooting that when we sighted a band of Indians we had only a few cartridges left in our belts. There was nothing to do but cut and run, so we started the cattle down the Clear Fork of the Brazos River and turned them loose. The Clear Fork was at swimming stage, so we swam our horses across. We then made for Fort Griffin, where all the good things of frontier life were to be had, such as whisky, tobacco, etc. We took along plenty of whisky, inside and out, tobacco and cartridges. We then returned to the place where we turned the cattle loose, and succeeded in rounding up most of them. After the roundup, we killed some buffalo calves and had a barbeque of our own. The meat was delicious, and we enjoyed it more than some people do a dinner at Delmonico's. We then picked our teeth, and started for Graham City, which was one of the few Texas towns on the map. When we arrived at Graham, we were in a swapping mood, and swapped a steer for some brandied cherries. Those cherries were very palatable, so palatable that we got gloriously drunk, and we lost our cattle again. With aching heads and parched throats, we started out to round them up once

more We found only a part of them, and then concluded we had better get them home before we lost them all.

One day Mr. Loving concluded to take a ride around the

ranch. He took Carr Hunt, Shad Damon and Ed Newcomb along for company. As they were riding along the opposite side of the valley, about nine miles from the ranch, they were surprised by a band of about one hundred and fifty Indians, who were looking for scalps and horses. They turned and ran into the timber. Proceeding along under cover until they reached a large and rocky promontory known as Lost Valley Peak, they ascended, completely throwing the Indians off their trail. They had outrun the Indians, as they had the best horses. Loving's policy was to keep the best horses that could be secured. Loving himself was mounted on a big Spanish horse about seventeen hands high - in fact, the biggest Spanish horse that I ever saw. As he was a very heavy man, he required a good, strong horse. Even this big Spanish horse gave out with him, and when he saw that the Indians had given up the chase, he had two of the boys double up, and they made a run for the ranch, leaving the Spanish horse and saddle on Lost Valley Peak. They could see the Indians away off in the valley, and they feared a raid on the ranch. Loving and his party were seven miles from the ranch when they made a dash for it. They made it all right, and I was stationed at the top of the big oak tree, to watch the band. They passed us up, however, and went on south through Jack, Montauk, and Clay Counties, killing and stealing as they went. They wound up their trail of blood by crossing Red River and returning to the Reservation a few days later. Among their depredations on this trip was the murder and mutilation of an old gray-haired man and woman. After killing them, they scalped them and mutilated their bodies terribly.

They did not even spare the little four-year-old granddaughter,

but ran a stake through her body and stuck it up on the fence which surrounded the house. At another point in the valley they "led a man by the name of Mason and his little boy. They then

took Mrs. Mason up to the top of a small wooded hill, where they tied her to a tree, and nine of them ravished her. Not being satisfied with that, and seeing she was in a delicate condition, they cut her open and took her unborn babe, which they hacked to pieces with their knives. After this horrible butchery, they departed, leaving the half-dead woman tied to the tree. She was dead when found a day or two later.

CHAPTER V

Winter on the Ranch

There were hundreds of wild cattle roaming over the Brazos River valley, and the first winter I spent on the ranch I had many opportunities to take a hand in their capture. It was a great sport,

and I enjoyed it immensely. If we could not corral the wild cattle, we tried to drive them off the ranch, as they would lead our gentle cattle away, causing us much trouble to recover them. We built a corral with long wings extending out on two sides, just on the edge of the prairie glades where the cattle would come out at night to graze. In order to trap the wild cattle, we would pen up a number of the domesticated animals, leaving them in the corral all day without food. By night they would be very hungry, when we would let them out between the two wings of the corral to graze. Concealing ourselves in the cedar-brakes, we would then await the coming of the wild cattle, which kept under cover during the day. The wild cattle, seeing the tame ones grazing quietly, would come out among them. We would generally wait four or five hours, in order to give all that were coming an opportunity to get thoroughly mixed up with our own cattle; then we would surround the whole herd and stampede them into the corral. In this way we secured many good cattle and many that were as wild as deer and never could be tamed. Among them would be steers and cows eight and ten years old and so used to wild life that they had become too "foxy" to domesticate. In stampeding the cattle to the corral, occasionally several of the wilder ones would attempt to break through our line and get back to the cedar-brake. We would shoot these on the spot, and the balance, seeing the fate of their leaders, would not make any further attempt to get away. We sometimes got a few deer and antelope in the corral with the cattle, and it might be added that we had a taste for antelope, just like a "cullud pusson" has for 'possum.

Another regular job we had was keeping the wolves away from the cattle, as the big Lobo wolves did much damage to unprotected herds. They would travel in packs of fifty or seventy-five and stealthily creep up to where the cattle were grazing,

when they would divide into several packs, each pack singling out a nice fat steer or heifer. Most of them would rush at the unfortunate animal's head, while one would come up from the rear and hamstring it, rendering it entirely helpless and an easy victim to their prey. Whenever we would sight a pack of Lobo wolves, we lost no time in heading them away from the cattle. They never attacked a man, but it took many cattle to satisfy their appetites. There were also plenty of coyotes howling around, but no one ever paid any attention to them.

When Christmas came around, we needed more supplies, especially whisky. What would Christmas be on the ranch without whisky anyway? We did not propose to get along without it, and I was selected to go to Paliponte for the goods. It wasn't half as hard a task to go to town for whisky and other supplies as it was to go for other supplies and no whisky. I hitched the team to a wagon we used to keep our horses' corn in, and set off alone. The wagon had a heavy oak top to keep the horses from getting the corn, and had I known the trouble it was destined to cause me, I would have been better prepared. The day was very cold, and a north wind was howling dismally across the valley. It began snowing a little as I neared the Brazos River, which had to be forded. The river was swift and high, and it was a case of swim for the horses, and get wet for me. I stopped, and got out to see what I could do in the way of keeping my wagon-bed and wagon together. Finding a short hitchrope, the only one I had with me, I tied it across the bed and around the sand-bolsters, and trusted to luck as to its being enough to hold things together. I wore a big overcoat, with cartridge-belt tied around me, and gloves.

It wasn't a pleasant task to survey, but I started in determined to get across at any cost, for I was going for frontier whisky for Christmas. I got along nicely until I struck deep water. Almost as soon as the horses began swimming I felt the lines tightening. I could not understand it, but eased up on the lines until I came to the end, when I knew there was something wrong. As the horses were swimming and the wagon floating, I could

not see what the trouble was, so I turned the horses back to the side of the river where I started. When I struck shallow water, I discovered that the top of the wagon floated while the wheels kept to the bottom. The water had raised the bed and sand-bolsters high enough to become uncoupled and the bed and rear wheels stayed with me while the front wheels went with the horses. It was a nice condition to be in when the current was swift and no help nearer than the ranch. I got out into the water and made an attempt to get the bed back into place, but it was top-heavy and the swift water turned it over on me. I was handicapped with a heavy overcoat, which the current acted upon like a strong wind does on a sail; but the boys had to have refreshments for Christmas, and it was "up to me" to deliver the goods. I stood on one edge of the bed and took hold of the other with my hands, and, by throwing my weight back, attempted to turn it over. It was a hard struggle, and it seemed as if every time I would get it almost over a wave would wash it back. I kept this up for half an hour, all the time gradually floating down stream, until the wagon struck a sandbar half a mile below. It stopped with a jerk, and, being numb with the cold, I lost my hold and went over backwards, taking one of the finest cold baths I ever had in my life. I went clear under, and, after floundering around in the water for some minutes weighted down by my heavy overcoat, I got straightened around and made for the shore. I then came back up the river, intending to go to a camp I had seen over on the hills while on my trip down. I found my horses had got out all right, but, like myself, were covered with ice and shivering with the cold. I tied up the harness, and, with my horses following, set out on a run for the camp, which was nearly a half-mile back and a short distance from the river; but instead of finding a nice warm fire awaiting me, I found the camp deserted and nothing but green wood to build a fire. It was a gloomy outlook, but I hunted around and found a rotten stump, from the inside of which I secured some dry, rotten wood. With this for kindling, I worked like a beaver, and finally got a fire started, but it was the slowest

burning fire I ever saw in my life. After a whole lot of shivering and wishing I were in a warmer place, I got pretty well warmed up and started back to get the balance of the wagon out of the river. Of course, if I hadn't been going for whisky, this trouble wouldn't have happened; but if I hadn't been going for whisky, I wouldn't have cared whether I ever got the old wagon out or not. It is needless to add that I got the wagon out, resumed my journey to Paliponte, purchased the necessary refreshments and eatables, and returned home safe and sound. When I told my troubles, the boys gave me the laugh right, and that night there was much good-natured repartee over the hot toddy.

A few days after my unceremonious ducking in the Brazos River, Budd Willot, George Mulligan, and I started out to round up a bunch of wild cattle which was grazing regularly in a small prairie near the timber. There was a small, rocky hill close to their grazing quarters. These hills were called peaks, as they were high and steep, more like a large mound than a hill. We hid our horses and ascended to the top of this peak to watch for the cattle to come out to graze. While waiting, we noticed a lot of broken rock thrown between two large ones, and as this looked suspicious, we investigated. On taking out the broken stones, we found the skeleton of an Indian and the usual big gray rat that is always found in an Indian's grave. The Indian had been buried with his arrows and soldier buttons, but the rat had discovered his resting-place and was making a home of it. The Indian's teeth and finger-bones were so white and perfect that we took them with us for ornaments. As we came up to the top of the peak again we saw the wild cattle grazing quietly, and a little further on were some deer and wild turkey. We then mounted our horses and started after the cattle. As soon as we came into view, the cattle saw us and broke for the timber. We had a race to head them off, and a five-foot ditch lay between us and the point we had to reach in order to turn the cattle. We let out our horses as fast as they could gallop, but in jumping the ditch the horses all went down, and we were sent sprawling on the grass. Before we

could get our horses up and mount, the cattle had the best of the race, and it was impossible to get between them and the timber; so we gave up for the day. As we were stoved up considerably, and not in any too good a humor, we concluded the Indian teeth and bones were a "hoodoo"; so we threw them away, and returned to the ranch empty-handed.

Ranger McIntire quit the hide business and joined the Texas Rangers responsible for the Lost Valley Area.

CHAPTER VII

With the Rangers

From Fort Jacksboro I went to Fort Griffin, and sold my buffalo-hunting outfit. From there I went up to Loving's ranch, in the Big Loss Valley, where I learned a big company of Texas Rangers, under Captain Hamilton, was camped. Ranger life looked pretty good to me, as there was forty dollars per month in it and plenty of plunder. So I applied to Captain Hamilton for admission into his company, and, as I was a large, stout, able-bodied man, with a good gun and a better horse, he was glad to accept me. The Rangers were camped in the valley near the ranch, and were scouting the country for Indians.

There was always something doing with the Rangers, and we kept the Indians busy keeping out of our way. One day we started out for a scouting trip up the Wichita, and struck a fresh trail. The band numbered thirty-five, and they had evidently just come in from the Reservation. We took up the trail and followed it all day. At dark we stopped to rest our horses and eat a lunch. After a short rest, we saddled up and took the trail again. The grass was tall and damp, and we could follow the trail as well at night as by day. We were in the saddle all night and by twelve o'clock the next day reached the Cox Mountains, where the great massacre had occurred, about eighteen months before. The Government supply-train on the way to Fort Griffin, in charge of a detachment of soldiers, was surrounded by Indians. Only one man escaped, the rest being massacred and the wagons burned.

The trail led up the side of the mountains, and we began the ascent. When we were about half way up, we saw two Indians coming toward us. They wore red blankets, and acted as if they hadn't seen us, until they came to within three hundred yards of our party. Then they suddenly looked up, and turned quickly and ran for a big gap in the mountains, which narrowed down to a cowtrail just wide enough for one cow to pass. The Indians Played their part well, and though we supposed it was a ruse to lead us into a trap, we knew there were only thirty-five in the band we were following, and did not fear that number, so we gave chase. There were twenty-nine in our party, including Adjt. Gen. Jones, of Texas, and Tom Wilson, sheriff of Paliponte County. We pulled right in after the two Indians, following the trail until we come to a big washout which had formed a basin. In this basin were concealed two hundred Indians, under the leadership of Big Tree and Satanta, where we expected to find only thirty-five. We rode up to within a hundred and fifty yards of them before we discovered that the original band had joined another and larger bunch. We has just discovered their presence when they opened fire, and eleven of our horses went down and three men were wounded. One had his left arm shot away, another was wounded in the leg, while the third received a shot in the back. We charged the Indians, and succeeded in stampeding them, much to the consternation of the two big chiefs, who ran in front of them waving their blankets, in an endeavor to stop the band. When they got about five hundred yards away, Big Tree and Satanta, who had taken in the situation at a glance, and knew they had a tremendous advantage over us with eleven of our horses gone, stopped the stampede. We realized fully the trouble we had gotten into when Satanta and Big Tree had their men lined up again; so we sought cover in a deep ditch, formed by washouts, which ran through a small grove of big trees. We tied our horses, and brought Billy Glass, who was wounded in the back, and the fellow who was wounded in the leg, whose name I don't remember, into the ravine with us, to keep them from being scalped. By this time the Indians were coming for us at full gallop. John Cone, whose arm was badly shot up, ran to the creek and dived into a water pool to hide. Tom Wilson was also cut off from joining us, and took a position behind a big oak tree. Another one of the boys, who had emptied his gun into the advancing Indians, was cut off, too, and he started down the creek with two Indians after him. He snapped his gun at them time after time, in an effort to check their pursuit; but they followed right after him with drawn lances, until he came to the waterhole where Cone was hiding, when he threw his gun at the Indians,and leaped into the pool. Cone, thinking he was an Indian, took a shot at him, but missed, and the Indians gave up the fight and joined the main band.

The Indians rode pell-mell right up to the ditch, and jumped their horses over our heads. This was our opportunity, and we made the best of it, shooting them as fast as we could fire while they were jumping the ditch. After they had all crossed, we had about thirty of their number down. Some were in the ditch, and some fell after they crossed. It taught them a lesson in regard to charging us, so they withdrew to a small rocky peak about three hundred yards distant from the top of which they could pick off every one in the ditch at the point where we were located. We moved farther down, to a more protected location, and they kept up a steady fire from the top of the peak, in a vain effort to dislodge us. Sheriff Wilson, who had still held his position behind the oak tree, tried several times to join us, but every time he would stick his head out a bullet from an Indian rifle would chip the bark too close for comfort.

In order to keep the Indians busy, we would push our hats up on the bank, and they would shoot them off instantly.

Billy Glass soon began to suffer for water, and, as he was mortally wounded, Ed Bailey and Knox Glass, a brother of the wounded man, volunteered to go to the creek and get it. It was all a man's life was worth to show his head, let alone go for water, but, as they rode racing horses, they stood a better show than the rest of the boys. The nearest point in the stream where they had to go for water was about three hundred yards distant, and the peak, where the Indians had taken up their position was about the same distance, only a little farther up. Bailey and Knox Glass took three canteens, and made a run for the trees where we had our horses tied. They mounted their fleet-footed racers, and reached the creek in double-quick time. The Indians, seeing their move, started in to cut off their retreat, and we kept a steady fire on the leaders to hold them back. Bailey was down by the water's edge and succeeded in filling two canteens before the Indians got a good start. Glass, seeing that they would have to hurry to keep from being cut off, said: "Come on, Ed; they are coming, and will cut us off." "No; I will fill this one, if they do catch me," was Bailey's reply. He did fill it, and mounted his horse. Glass was off like a flash, and made the ditch where we were entrenched easily; but Bailey failed to take advantage of his horses's fleetness, and was the victim of the most horrible butchery I ever witnessed.

Instead of letting his horse out as Glass did, Bailey seemed confused, and held him in. His horse was exceptionally fast, and, with the bad start, he had a chance to make it; but he did not head straight for the ditch, and in a few seconds the Indians had him cut off. They closed in on him, driving him around in a circle, all the time shooting arrows into him and yelling with fiendish glee. We were powerless to come to his rescue, as the only way we could cope with such a large body of Indians was by fighting them from cover. Our ammunition was running low, and only eighty rounds of cartridges remained, when the adjutant-general ordered us to cease firing. He saw that saving Bailey was out of the question, and it was absolutely necessary that we reserve our ammunition, in the event of a charge from the main body of Indians, which was likely to take place at any time.

After shooting seventeen arrows into Bailey's back, they rode up and pulled him from his horse. Then we were compelled to witness the most revolting sight of our lives. They held Bailey up in full view, and cut him up, and ate him alive. They started by cutting off his nose and ears; then hands and arms. As fast as a piece was cut off, they would grab it, and eat it as ravenously as the most voracious wild beast.

We were all hardened to rough life, and daily witnessed scenes that would make a "tenderfoot's" blood run cold; but to see Ed Bailey die by inches and eaten piecemeal by the bloodthirsty Comanches and Kiowas made our hearts quail. We could see the blood running from their mouths as they munched the still quivering flesh. They would bat their eyes and lick their mouths after every mouthful. The effect of these disgusting movements on us was but to increase our desire for revenge, and we often had it later on. After eating all the fleshy parts of our brave comrade, they left him lying where they had captured him, and returned to the peak. The Indians remained on the peak or behind it until dark, and we spent the rest of the afternoon in the ditch, but keeping a good lookout. We had ceased firing, as Adjt. Gen. Jones' orders were not to fire until they were within fifty yards of us, so we could secure the ammunition of the dead or wounded Indians. However, none came that near; but there were plenty of dead ones on all sides, that we had killed before our ammunition ran low.

Along in the evening Billy Glass died, the Indian bullet having penetrated his stomach and lungs. About 8 o'clock we took the remains of Glass, and struck out for Fort Jacksboro, twenty-five miles away, to get reinforcements from the soldiers quartered there. As soon as we were well on the road, and felt safe from pursuit, we dug a grave and buried Glass. There was a lot of colored troops at Fort Jacksboro, and the officers detailed two hundred of them to return with us and put the Indians to rout. They made so much noise while on the march that we could not hope to surprise the Indians. An Indian could have heard those darkies singing and laughing a mile away, but they furnished us with plenty of amusement on the way. When we neared the battlefield, we struck camp until daylight. We had all kinds of trouble in keeping the "n------" quiet, as they would rather have frightened the Indians away by their noise than have defeated them in battle. One big black, who was blacker than the ace of spades, refused to take his post on the picket-line; so they hung him up by the thumbs to a convenient oak tree, and left him there for four hours. At daybreak we rode over to the scene of our encounter of the day before, but there was not an Indian in sight. We first gathered up the remains of Ed Bailey for burial. Nothing but the skeleton and the internal organs remained, as the Indians had eaten all the meat off the bones.

After burying Bailey, we tried to locate the Indians. Although the ground was strewn with bodies the day before, they had gathered up all their dead and wounded, and made off. We struck their trail, leading to Fort Sill, but the colored soldiers wouldn't follow it, and, after looking around awhile, we returned to Fort Jacksboro."

Big Tree and Satanta, the big chiefs of the band, were afterward captured and sent to prison by the officers at Fort Sill.

Another adventure, that is worth recording here, took place just one month from the day we had the fight in the ditch. The moon was full, and the Indians full of deviltry, so we went out on a scouting trip, hoping we might run across some marauding parties. We stopped near the place of our former fight, and, looking across the valley, saw seven Indians on the other side, headed directly toward us. We fell back into the timber, and awaited their coming. They stopped at a creek about a mile away, and watered their horses. They stood there for some time, and then came out of the creek single file, and started for the timber where we were hidden. From the direction they were coming, we estimated that they would strike the timber where there was a high bench about a hundred feet back from the edge of the prairie. We hid ourselves accordingly.

Finally they came along, whittling out dogwood arrows, and chatting together. They entered the timber just where we wanted them to, when we rushed out, and fell in behind them, cutting off their retreat. As there was the high bench in front of them, and we were behind them, they couldn't get away. Only about half of our company of Rangers was present, the other half being down with the measles, and the rest of the company was made up of an escort from another company, under Lieut. Long. We were armed with the new 45-caliber Colt's revolvers and new carbine needle-guns. We had received them only a few days before, and they were a great improvement over our old cap-and-ball navies and Spencer and Henry rifles. They were up-to-date weapons, and the carbine rifle is even today the best gun for general use.

They hadn't heard us fall in behind them, and they kept on in single file until they came to the bench, when we made a rush on them. They were taken by surprise, and started to run, when Lieut. Long pulled his six-shooter and fired the first shot. He caught an Indian in the back and uncoupled him. There were two deep ditches, which formed a "V," having been washed out in that shape by heavy rains; so wide that they couldn't jump them at night, and they were compelled to turn and meet us. There were five bucks, a squaw, and a renegade white man in the party. We all opened fire on them, but, as the timber was thick, our fire wasn't as effective as it would have been under other conditions. Three of the bucks went down, when the squaw went into action. She emptied two six-shooters at us, but none of the shots took effect. Then, jumping from her horse, she clasped her hands on her breast, shouting, "Me squaw, me squaw," thinking she would get off because she was a woman. Someone shot her in the stomach, as a squaw horsethief wasn't considered any better than a buck horsethief, and she walked over and sat down by a tree. Lieut. Long became engaged in a hand-to-hand encounter with the chief of the Indian raiders, after each had emptied his gun. They clinched and were struggling on the ground when we came up. The lieutenant was a big, powerful man and so was the Indian. We put our guns to the Indian's head and asked him if he would surrender. "No, you heap Tahones (Texas) s--- of b------," said the Indian in reply; and we fired, shooting his head clear off. Only a small piece of his skull remained, and that stuck to the back of his neck. That made five down.

One Indian, who was riding a little mare which he had stolen from Loving, discovered an opening around the ditch and went through, making his escape. We sent a shower of bullets after him, but he was riding like lightning, and we never knew whether we hit him or not.

The renegade was the only one left, and he got a half mile away before we got him. We killed his horse first, and he got behind the dead animal, lying there with his gun cocked, but he did not fire a shot. We couldn't understand why he didn't shoot at us, as a renegade receives less quarter than an Indian when captured. He bobbed his head up and down behind the horse so we couldn't get a shot at him. We dismounted and crept up to some trees a short distance from the spot, and took turn about in shooting at his head every time it would appear above the horse's body. Finally one of the boys caught him between the eyes, and the renegade's raiding days were over. The bullet tore off the top of his head, and he was dead before we reached him. On examination, we found that he had been shot through twice before we had killed his horse, which accounted for his strange actions. He was apparently bewildered and so could not shoot us.

We went back to where the Indians lay, and found the squaw still alive, nursing her wound in the stomach. Another well-aimed shot put an end to her; then we proceeded to skin them. I skinned the squaw, taking only the skin from the body proper, leaving the arms, neck, and legs. We tanned these Indian hides afterwards, and I made a purse out of the squaw's belly. The boys made quirts (a kind of a braided riding whip) out of the bucks' hides.

From the Big Loss Valley we moved to Flattop Mountain, on Salt Creek Prairie, where we camped nearly two months. There was good water here, and Flattop Mountain afforded an excellent view to watch the movements of the Indians. The time passed quietly while we were camped here, and we didn't hear of any Indian depredations anywhere. One day, while some of the boys were grazing their horses near the scene of the massacre of the Government muletrain, they found an Indian grave in a pile of rock, and dug it out. The Indian had evidently been buried many years, as the bones of the skeleton were whitened and showed marks of age. In the grave, behind the body, they found two ladies' gold breastpins, a gold ring, a butcher-knife, several strings of beads, a soldier's overcoat, bow and arrow, and five shooters. The six-shooters were well greased with tallow, to keep them from rusting, and one of them had been fired off once. It was the custom among the Indians to bury a brave's earthly possessions with him and, as they were continually raiding the settlements, stealing everything that was of value, there was almost always enough in a grave to pay for digging it up. The boys on the frontier never failed to rifle an Indian's grave every time they found one.

From Flattop Mountain we moved to a point on the Brazos River near the round timber, where we camped about two months. During a rainy season, while we were camped here, the Indians came down the river. We struck the trail of a large band, and started to run them down. It had rained hard every day for several days, and the Brazos River was full nearly to overflowing; so we rode down the river a little way, for the best place to swim it. On the other side we took up the trail again, and followed it for some distance, until it led into a mesquite flat. The prairie was so soft that our horses had difficulty in getting over it, which necessarily made our pursuit slow. We hunted the flat over for Indians, but we found only one, a squaw, who was the wife of old Black Crow. It seemed that Black Crow was in the habit of beating his wife, just as some of his civilized white brothers do, and on this occasion he had beaten her and driven her back. She was resting in the mesquite flat when we found her, and when she saw us, she tied her pony to a mesquite tree and threw her arms and legs around another, holding on with all her strength. We broke he hold, and took her along to camp. We kept her with us for two months, when Black Crow, learning where she was, appealed to the officers at Fort Sill, who furnished him with a squad of soldiers to come out to our camp and get her. During her stay in camp she appeared to be quite contented, especially as we kept her in the commissary, where she could eat all the sugar she wanted. She had a woman's sweet tooth, and went after the sugar just the same as a society girl after chocolates and bon-bons, eating as high as a quart during the night. She was also cleanly in her habits, which is more than can be said of the average squaw, and would go to the creek and wash herself three times a day. When Black Crow and the soldiers came and demanded her release, she did not want to go with them. She kicked, and scratched, and bit, when Black Crow took hold of her to force her to return to his bed and board; but when she saw he wouldn't return without her, she gave up the struggle and went along. It was not recorded whether Black Crow gave her regular beatings after that or not, but they are still living together on Cash [Cache] Creek, near Lawton, Oklahoma.

Occasionally a man comes out to the frontier full of bravery and braggadocio, and we picked up such a man for the company. He was from Arkansas, and what he hadn't done, and what he wouldn't do in Texas, were too trivial for consideration. We tested his courage one night, and found it just what we expected, a little yellow. To keep the Indians from stampeding the horses, we drove them into the corral every night, and took turn about in guarding them. When it came Ark's turn, as we called him, he wasn't quite so enthusiastic, but took his place at the proper time. We had a bear skin in camp, and a fellow named Yarborough got it out, and tied a lariat to it, leaving it alongside the corral, then with the other end of the lariat secreted himself along the bank of the creek running by the camp. He pulled this bear hide along the ground past the corral, and it made the horses frantic. They snorted and reared and plunged, while Ark only hit the high places between the corral and camp, yelling "Indians!" at the top of his voice with every jump. We were all "on," and, grabbing our guns, rushed out to carry out our part of the programme. Of course we searched the premises, but found nothing. In the meantime Yarborough had pulled the bear hide down into the creek, and, as there was nothing doing, we assured Ark that he had nothing to fear, pulled the bear skin to the opposite side of the corral again, and went back to the camp. After giving Ark a few minutes to quiet his nerves, Yarborough pulled on the bear skin again. When Ark saw the big black bear thing crawling around the corral toward him, and the horses in a tempest, he was frightened worse than before, and, letting out a yell that awoke the prairie for miles around, he made the distance from the corral to camp in recordbreaking time. We all went out again, and this time found the bear hide which was the cause of Ark's trouble. We "jollied" him about allowing such a little thing to frighten him; then he got mad and threatened vengeance. Next morning he found out in some way that Yarborough was the man who manipulated the rope, and promptly challenged him to fight a duel. It was an affair of honor, and the gentleman from the Ozarks did not enjoy having his honor trampled upon. Yarborough just as promptly accepted his challenge, and it was agreed that the management of the affair should be placed in the hands of Captain Hamilton. We were all "in on the deal," and the arrangements were made with all the solemnity of the real thing. Eleven o'clock that morning was the time scheduled for the duel to be fought, and Ark carefully watched every move that was made until time was called. A few minutes before the appointed hour we assembled on a nice grassy plot alongside the creek, and lined up with six-shooters in hand. The captain took his position in front of us, and called to both men to step forward. The captain, having the loading of the pistols, had extracted the bullets from six cartridges, and loaded each weapon with three blanks. He instructed them as follows: "Stand with your backs to each other, holding the guns down by the side; step off fifteen paces, and, at the count of 'three,' wheel and fire." In handing them the guns, the captain took good care to keep them pointed downward, so they couldn't see that they were not loaded. They took their positions, and the captain ordered, "March!" They stepped off fifteen paces each, and were standing with their backs to each other, when the captain began to count slowly, with a deep, resonant voice, which sounded very solemn indeed. The stillness was oppressive. When the count began, "One," Ark showed signs of nervousness - the oppressive stillness was telling on him; "Two," and Ark first turned his head, then turned clear around, and, in a whipped-dog tone, said: "Gentlemen, I weaken." Just then the captain yelled, "Three!" and Yarborough wheeled and fired. The brave gentleman from Arkansas dropped his gun, and hit the prairie with the speed of a jackrabbit. Yarborough was right after him, but he couldn't have been caught with a locomotive. He made straight for the settlements, and we were afterwards informed that he never stopped until he reached Arkansas. He left a good horse and eighty dollars pay coming.

Yarborough was afterward appointed marshal of Albuquerque, New Mexico; but he was too handy with his six-shooter, and, after killing two men, was hanged.

CHAPTER VIII

Weeding out the Outlaws

Our next orders were to go to Fort Griffin, and from there proceed against the outlaws who were making the frontier of Texas their temporary home. At this time Texas was the Mecca for criminals driven out of other States, and, except for the Texas Rangers, they were out of reach of the law. If a man had committed robbery or murder in Ohio, Illinois, or any settled State, and it wasn't safe for him where officers of the law could reach him, he made a beeline for Texas. On the frontier they would hunt buffalo and work on the ranches without fear of molestation, as no officer from the cities or counties of other States would undertake to follow a man through the hostile Indian country. This class of criminals were becoming very thick in Texas, and the authorities were besieged with appeals from State, county, and city officials all over the country to arrest the fugitives. At Fort Griffin we were loaded with warrants, and then proceeded to the buffalo grounds to execute them. The first month we arrested one hundred and two men who were wanted for crimes in other States, and delivered them up to the forts, to await the arrival of officers. After cleaning up the buffalo grounds, we were ordered to go to Montague County to effect the arrest of culprits named Cribbs and Preston, and the Brown brothers, who had murdered the Meeks family. The brush was so thick that the sheriff and his deputies had about given up hope of capturing them. There were so many hiding-places that the criminals had no trouble in eluding the sheriff's party, but they found they were "up against" a different proposition when they had the Rangers to deal with. When we reached the vicinity where the fugitives were supposed to be hiding, we camped around in the brush, and in a short time succeeded in capturing all four. We took our Prisoners to Gainesville, which had a better jail than Montague, as the sheriff was afraid of a lynching. They were afterwards tried in Gainesville on a change of venue, convicted of murder, and hanged.

The day we left Gainesville, we got to sampling the whisky tap at the various bars, and found it so much to our liking that we each took a quart bottle along. The result of it was that we got good and drunk before we got out of town. Sheriff Perkins of Montague County, was with us, and he took a turn at "shooting up" the town. After he had finished this innocent bit of entertainment, we saddled our horses, and set out for Montague, each man carrying his quart of whisky in his saddle-pocket. While riding over the trail two abreast, the sheriff and the captain in the lead, a little puff of wind blew the sheriff's hat off. I was riding next behind the sheriff, and when his hat blew off, I pulled my gun and shot a hole in it. The rest of the boys did the same; but the sheriff didn't like it, and was hot all the way through. The captain, however, laughed at him and "jollied" him until he cooled off. We hadn't gone far until the captain's hat blew off, and it was treated in the same way. That started the ball rolling, and it ended in every one's having his hat shot full of holes. One of the party wouldn't "stand for it," and struck out across the prairie. He was riding a good horse, and we chased him three miles before we caught him, and threw his hat up in the air, riddling it with bullets. We were now all hatless, and had an all-day ride through the hot sun before we could reach Montague. We made the best of the situation, however, and laughed and joked our troubles away. We rode into Montague hatless, but proceeded at once in search of something that would answer the purpose. That was all we found, too, as there were only two hats in the town of the style we wore; and we were compelled to buy some small, white, cotton hats until we could reach another town and find what we wanted.

From Montague we rode back to Fort Griffin, where the local vigilance committee was making trouble. Here we found hats that we felt right in. The vigilance committee had been running things with a high hand, in hanging men without trial, and before they got through they had a split-up in their ranks. The two factions then organized two separate committees, one calling themselves Moderators, and the other Regulators. The Moderators protested against hanging a man without trial or investigation to determine whether he was guilty or not, while the Regulators wanted to hang every man who could not give a good account of himself. The result was a bitter war between the two committees, and they got to killing each other. Johnny Long, ex-sheriff of Shackelford County, was one of the leading Moderators, and, being a dangerous man in a row, the Regulators determined to get rid of him. They had him arrested and placed in an improvised jail and chained down with nine other prisoners. During the night someone, supposed to be a Regulator, got into the lockup and shot and killed him. Long was a friend of Bill Gilson, the marshal, and Gilson hunted me up and told me the whole story. I got him a new suit of clothes and took him down to the river bank. There I had him change clothes, and, after shooting his hat and clothes, scattered them along the bank, so as to indicate that he was murdered and his body thrown into the river. By this time the Regulators got wind of the fact that Gilson had given them away, and they started out to hunt for him. They didn't search long until they found his clothes. They were suspicious of being tricked, and, before taking any action, all the members got together and compared notes. It developed that none of them had killed him, and they continued their search. We had a pretty good start by this time, as I put Gilson on a big State mule and we rode all night, reaching the Brazos River in the Fish Creek Mountains before halting. Gilson was a hard drinker and got the "jim-jams" on my hands. I took him to an old friend who was camped down on the Fish Creek Mountains. I swam my horse across the river and rode over to Fort Belknap, where I bought some whisky for him, and returned. As soon as he got a little whisky into him, he was all right; so I went back to camp and picked up a few of the boys. We returned and got Gilson, taking him to Austin, where he told the State authorities all about the workings of the rival vigilance committees at Fort Griffin. The officials were very much worked up over it, and issued warrants for the arrest of the whole outfit. We went back to Fort Griffin and arrested them all.

They furnished bail and went down to Austin to "square it" with the authorities. It cost them about $50,000 to get out of the scrape, and that broke up the vigilance business at Fort Griffin. We were then ordered to arrest Sam Bass and his band of Union Pacific trainrobbers, who were making the frontier their home for the present. We located them in a cedar brake on Ironeye Creek, in Paliponte County. We entered the brake, but they gave us the slip and got away. We didn't like hunting white men, so didn't follow them any farther, but returned to camp. Captain Hamilton quit the company and many of the boys followed suit. I was left in charge, and decided to disband the company; so I took all of the outfit which belonged to the State to Thorp Spring, where I turned it over to June Peak, who was organizing a new company at Dallas, to hunt Sam Bass and the other Union Pacific trainrobbers. We disbanded here, and the boys who had remained with me went home.

Following his stint with the Rangers, McIntire opened a bar in Fort Belknap.

CHAPTER IX

Running a Saloon in Texas

While I was with the Rangers, my chum and bunkmate was N. F. Lock, and when Company B disbanded, we remained together. We were undecided as to what to do for the future, and went to Fort Belknap in search of almost any old kind of an opening. There was no saloon there, and, for want of something better to do, we opened up one. I tended bar and managed the saloon, while my partner found employment as a clerk in a general store. The saloon business proved a good venture, as business was lively and money plenty. Everything was 25 cents a drink, as silver quarters and 25-cent shinplasters were the smallest denominations in circulation. No two-for-a-quarter drinks "went," and nobody expected it.

Millet Brothers had a large cattle ranch near the Fort, and employed a large number of "punchers." They were a tough lot, too, as Millet Brothers would not hire a man unless he was a fighter. They did a lot of shady work, and needed good men to execute their plans in raiding the ranges for stray cattle. The men from Millet Brothers' ranch were regular patrons at our bar, and they would come in in bunches of from twenty-five to fifty. The first place they headed for on reaching Fort Belknap was the bar, where they would all line up and drink round after round of frontier whisky. At this stage I would begin watering the whisky, and gradually get it so weak that it would hardly be recognized as whisky. I did this in order to keep them from getting too full. I would also manage to collect about twice for every round. One man would order the drinks and pay for the same, and then I would go to the other end of the bar and pick out another fellow, saying that the last round of drinks was on him. They never "tumbled," and always had plenty of money. By giving them watered whisky, it would not be long until they were all right again, and ready to start in over again. By keeping this up all afternoon, or all evening, I would have a nice little sum of money to show for my day's business.

One night Charley Roberts brought a crowd of his men in and lined up at the bar. By 11 o'clock they were all "loaded," and, as there were no other customers in the saloon, I decided to close up, as I did not want them to become any drunker. They didn't like the idea, and tried to run a bluff on me, saying they would saddle up their horses and kill me, and run the d----d place themselves, if I would not give them anything more to drink. I told them I was running the place and would be there when they returned. Out they all went for their horses, and I prepared to give them a warm reception when they returned. It was in the summer and the weather was very warm. My partner, Lock, was sleeping on a blanket on the ground just outside the rear of the saloon, where we had living apartments, and overheard all the crowd had said. I armed myself with a Winchester, two six-shooters, and a shotgun, then raised the window and awaited their coming. I could hear them riding along, and was prepared to cut loose at them as soon as they came in sight. Lock had not as yet said a word to me, but when the sound of the horse's hoofs rang out on the night air, he stepped in with his Winchester under his arm and asked, "How are you fixed?" I replied that I was fixed O.K., and he said he was ready for them. Knowing where I slept, they rode right up to the window, whereupon I jumped right out among them with two six-shooters, threatening to kill every one of them if they didn't drop their guns. They all complied when they saw I had the drop on them. There was a big, loud-mouthed fellow in the crowd, who was responsible for starting all the trouble, so we ordered him to leave town immediately. He accepted the order without a word and departed at once. Now that it was all over, the boys were feeling all right and insisted on staying. They unsaddled and it was two days before they left. During these two days I took in $200 and I had no more trouble. That was the last trouble I had with the cowboys while I was in the saloon business.

Business continued good, and I had no more fights in the saloon for some time. There were two rival merchants in the town, whose names were Clark and Martin, and both were regular patrons of the bar. Both were anxious to have me "boost" for them; but to "boost" for one was to lose the trade of the other and I turned them both down. As they visited the bar frequently, they would often meet there, and invariably quarreled. One night they met in the saloon, and nothing would do but they must fight it out. I agreed to let them fight, if they would strip and go into the back room. And I further agreed to act as referee, and stand for fair play. When both were stripped, I called time, and they went at it. They were pummeling each other at a merry clip, when I opened the back door and pushed them both out. The yard was full of sandburrs about an inch deep, and over they went, rolling in the sandburrs. When they got up, they were a sight to see, all covered with sandburrs and madder than "wet hens." I shut the door in their faces and refused to give them their clothes. They were still full of fight, and concluded to go over to Clark's store and fight it out. A camp-meeting was being held just below the saloon, and as the fight occurred at the time when the people were coming home from the services, they were compelled to pass through the crowd to reach the store, where they had agreed to finish the fight which the sand-burrs had so unceremoniously caused them to temporarily abandon. They did not seem to mind the people, as they were mad, and determined to get down to business again without delay. The church people were completely flustrated at first, and the women blushed their deepest. Their escorts, however, enjoyed the situation immensely, and took to "joshing" the naked fighters for all there was in it. As it was evident that something had happened, the men hurried their wives home and returned to the saloon for particulars. They discussed the situation over their drinks until a late hour, and the bar did a thriving business. Next morning I took their clothes over to their respective stores. They both had black eyes, bloody noses, etc, and were pretty badly punished. The floor of Clark's store, where the melee was continued, was strewn with broken candy jars, candy, flour, etc., and presented as sorry a looking sight as the principals. They were separated before they could decide which was the best man, so I thought I would act as peacemaker and set them right before they got together again. I made them both come over to my saloon and shake hands over a social drink. They were reluctant to make up, but I insisted, and after we had several drinks they were to all appearances all right again. They were very sore on account of their experience with the sandburrs, which stuck into their flesh like needles, and it was several days before they fully recovered from the effects. Martin was afterwards murdered for his money, while Clark got into two fights in succession and killed his man each time, then left the town, and was never heard of in that section again.

About this time Lock and I received an offer to sell out, which we accepted, clearing up a nice little sum of money. We then went to San Antonio and invested our money in sheep. We drove them to a point in Shackelford County, above Fort Griffin, and started in to raise sheep. We were allowing them to run over the range without protection, when we were surprised by a snowstorm. Snow fell to the depth of sixteen inches, and it was bitter cold. When the weather cleared and we went out to round up our flock, we found that half of them had perished in the storm. We skinned the dead sheep, and by selling their pelts saved ourselves from a total loss. This experience with sheep was enough for us, and we sold out at the first opportunity. As the saloon business was pretty good, and not likely to freeze up, we determined to try it again, so we went to Mobeetie and opened up. Mobeetie at this time had only three or four residences and a couple of stores, but there was one vacant building and we rented it. There was another saloon in the village, and that was owned by Henry Fleming, the sheriff. We prospered in spite of competition, as whisky was still 25 cents per drink, and there were plenty of customers. I got tired of it after a time and sold out to my partner, to accept a position as deputy sheriff under Fleming. In those days the rough element was in a majority and it took constant watching to keep them in order. Every county did not have its sheriff and deputies as now, and Fleming had twelve attached counties to cover. His territory took in all the northwestern part of Texas to New Mexico and No Man's Land.