Texas Forts Trail Driveby Wendi Lundquist |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

I once read in Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek that the Indians carved grooves into their arrow shafts, so that the blood from an animal pierced but not slain could stream down the arrow and paint a trail on the ground for the hunter to follow. The Indian 'lightning mark' is a smart, simple invention that creates an unmistakable path of evidence leading eventually to the honored prize of food or fur.

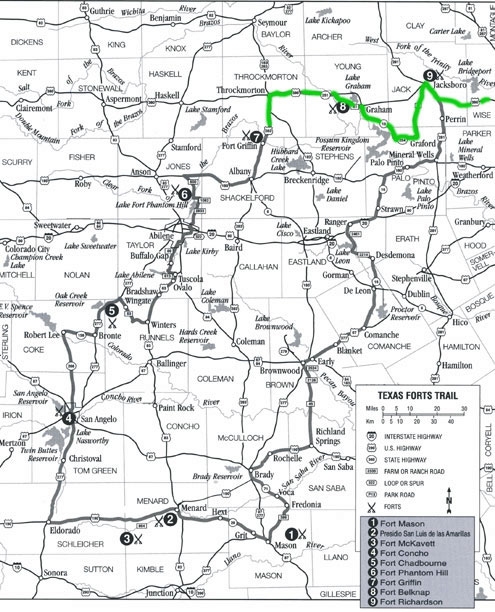

Amidst the Texas frontier, in the mid 1800's, the Indians who were here for thousands of years, and the whites who had traveled hundreds of long, grueling miles in large caravans from the eastern states fought for possession of the open range. Both parties had a bellicose, courageous spirit that would not allow them to forfeit their claim, which was a virtual paradise of wild game, an abundance of water, mountains and prairies. This road trip focuses on the war itself, passing both the actual forts built to house the troops and supplies needed to defeat the passionate Comanches and the less renowned places where particular citizens confronted small groups of Indians. In some way, for me, following the Texas Forts Trail was like drawing back a mighty bow and shooting a mystic arrow back through time. We traced this route like the Indian archer would follow a trail of blood, to discover its source, however vicious or tame.

We started out of Fort Worth going west on I-20 through Weatherford. We picked up the Forts Trail at Highway 16, heading north through Strawn. With a population of 694, Strawn boasts the work of a range of artisans, from soap and candle makers to metal sculptors. It was early on a Saturday morning when we drove through town, and we stopped to take a few pictures of the bronze sculptures set on display just outside the main square. There was a giant armadillo that spanned at least fifteen feet, and a cleverly assembled dung beetle, in its characteristic handstand formation, working hard to roll a giant ball with its back legs. Unique culture abounds in this town, though its residents appear to sleep late. We didn't see a single soul entering or exiting the shops, and the well-known Mary's Cafe was closed.

|

|

Strawn lies in Palo Pinto County, an area thick with stories of encounters with Indians. Our drive north on Highway 16 passes right through the area where W.J. Hale twice fought with Indians. In 1871, according to Hale himself, Indians ambushed him as he made his way to Palo Pinto. Just as he crossed Ioni Creek, the air was suddenly filled with arrows sailing toward him. He had a six-shooter on either side, and he fired them both as he ran. A little further eastward, he was finally able to fend them off with a few shots from his Winchester. Apparently in those days, if you were to occupy the same land as the Comanche warrior, you didn't venture far from home without adequate ammunition. Hale survived another skirmish in 1872, just nine miles northeast of Strawn. The Indians surrounded him, and he fired upon them, striking their leader. They quickly fled, and Hale was once again able to scramble to safety.

Where 16 intersects at Hwy 180, just a few miles west of Palo Pinto, a young ranch hand named Fred Colley was attacked by several Indians. He was riding a good horse, so he attempted to outrun them. Joseph Carroll McConnell describes the final scene of Colley's life in his book The West Texas Frontier: "During his dash for life, an Indian with his bow and arrows, gave Colley a mortal wound. [He] pulled the arrow from his body and used it to whip his horse. When he reached the fence of the Dodson Ranch, after running about two miles, young Colley fell dead."

Another famous murder that happened along Ioni Creek was Jesse Veale's. In his book, Goodbye to a River, John Graves describes what he imagines might have happened the day Jesse Veale and his friend Joe Corbin stole a few of the Indians' horses, left unattended in a grove of cedar.

"Jesse," Joe Corbin said, "they's two Indians a-lookin' at us from on top of that bank. They's more than two..."

Afoot, likely because it had been their ponies the boys had taken upriver, the Comanches began to shoot, and an arrow hit Jesse Veale in the knee, and his horse went to bucking off to one side. Joe Corbin yelled: "What the hell we gonna do?"

Jesse yelled something back. To Joe Corbin it sounded like: "Run it out!" He did, snapping his useless pistol at an Indian who tried to grab his reins and ducked aside from the misfire, lashing his pony on up the bank's rise... When he last looked back (how many times did he see it again, the rest of his life, how many times did he wonder if what Jesse Veale had said was "Fight it out"?), Jesse was on the ground shooting and clubbing with his pistol, and they were all over him. And when Joe Corbin came back with help from a ranch not far away, they found Jesse Veale sitting dead but unscalped against a double-elm tree, his pistol gone, Comanche blood on the ground around him.

Both Indians and whites lost their lives, avenging the theft of horses or the murder of ones honored and loved. In an endless chain of revenge it seems, neither side would allow the other to have the last victory.

We turned west on Highway 180 and witnessed a stark transformation in the landscape. A low road, slicing a path through the Palo Pinto mountains, Highway 180 is lined on either side with only cedar, cactus, and rock, and it looks like it hasn't changed significantly since the time of the old frontier. The blood-soaked banks of Ioni Creek and the bones found at Metcalf Gap could testify to the violence of the era, proving that survival on Texas land came at no small price.

In this area of our drive otherwise devoid of the seasonal fiery reds and oranges, the town of Caddo arises, named for the colorful Caddo Indian tribe that dominated the eastern Texas frontier for hundreds of years. At the junction of Hwy 180 and Farm Road 717 lies the historical marker for Caddo; the town was settled just a few miles from the place along Caddo Creek where its namesake Indian tribe resided. The majority of the Caddo lived in East Texas and parts of Louisiana, with the greatest concentration of people around Nacogdoches. They were a farming culture, and they gained the respect of French and Spanish explorers who admired their artful pottery and attractive clothing.

Hwy 180 west leads to Breckenridge, and on the day we drove through, the town ate their Saturday morning breakfast with at least one eye peering out the window, the mark of anticipation for the annual Christmas Parade. Inside Peg & Greg's Cafe, the patrons were attired in red sweatshirts and sweaters, sparkling with appliques of teddy bears and rocking horses. Inside comfortable shoes, they wore socks with bells that jingled. We stopped to eat, but we settled for coffee because the waitress was remarkably preoccupied with the coming of the parade. She was pleased to report, when we sat down in a booth by the window, that we had the "best seats in the house."

We continued west on 180 across the bridge at Hubbard Creek Lake and turned north on Highway 283 at the town of Albany toward Fort Griffin State Park. During the time of the Indian wars, Fort Griffin served as a center of operations for the military. After a few years of conflict, the Indians moved further west, and the area surrounding Fort Griffin was rendered safe for white settlers. Now, the park provides facilities for camping and hiking, and serves as residence for a herd of Texas longhorns. Fort Griffin was situated on top of a hill, and a town of the same name developed in the bottomland between the hill and the clear fork of the Brazos River. What came to be known as The Flats quickly gained a reputation for lawlessness, and it attracted such famous outlaws as "The Poker Queen" Lottie Deno, Mollie McCabe, and John Wesley Hardin. The most famous of law enforcers also spent some time in The Flats, specifically, Doc Holliday, Wyatt Earp, and Patrick F. Garrett. In Albany, we drove past the Hereford Motel, a modern rendition of the Flats, with awnings bearing old names such as "Lottie's" and "The Beehive Saloon." Nearby, a sign hailed us as we drove through town, "Visitors Y'all Are the Greatest!"

|

|

On Highway 283, the prominent color scheme was that of dry hay and the rust of corrugated metal, usually partially serving as the walls and roof for an old barn or shed. The absence of green in the view of a landscape always seems to get my attention because it isn't what we've come to expect. Green grass and blue skies, the rudimentary elements of nature, are easier to imagine out there along the roadside, but a palette of only sepia shades looks like the artificial creation of a painter.

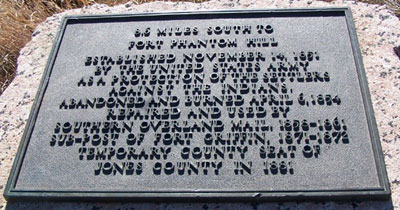

Out of Albany, we headed further west on Hwy 180 until we passed a highway marker that read "8.6 Miles South to Fort Phantom Hill." We decided to try our luck, so we turned south onto County Road 329, zigzagging through pastures on a rough gravel road for about 6 miles, and eventually coming out at Highway 600, just 2 miles from the Fort. In Along the Texas Forts Trail, Aston and Taylor provide two explanations for how this fort came to be called "Phantom Hill":

On approaching the post you will see the remaining chimneys standing like sentinels on what looks like a formidable hill overlooking the Clear Fork of the Brazos. As one nears the hill it disappears and becomes a gentle slope, barely perceptible when one arrives; thus one of the stories of how the post got its name. A second account has to do with a nervous sentry firing on what he thought was an Indian on the hill. A following investigation failed to discover the presence of any Indians, and one of the troopers suggested that the man had seen a ghost.

Although a few of the old buildings still stand, and they are visible from the road, Fort Phantom Hill has no entrance to the public, even for a walk through the grounds. When Phantom Hill was first built, the times spent there were characterized by mostly hardship. The men stationed at the fort did not see any major Indian battles; "the only break in the monotony of fort life was excursions into the field, which meant extended marches across arid land with inadequate supplies of food and water."

As you drive past Fort Phantom Hill, Hwy 600 south will take you through Abilene along the Forts Trail to 277 south. In this segment of the trip, it's worth slowing down to gaze out the window. The horizon on either side is lush green and mountainous. Turn off at Farm Road 1235, where a sign points the way to Buffalo Gap 7 miles ahead. Named for the prolific amounts of buffalo that passed through a "gap" in the Callahan Divide, this area was frequently traveled by Indians, buffalo hunters, and even Spanish Explorers in earlier centuries because there was water and an abundance of game.

At the entrance to the Historic Village, we browsed through an elaborate gift shop and museum, whose clerks and tour guides all wore the costumes of the frontier period. Aston and Taylor describe this picturesque stop Along the Texas Forts Trail:

Today visitors to Buffalo Gap will still find it a village nestled among the oaks. The two-story county jail constructed of native stone blocks and mortised together with cannonballs brought from Civil War battlefields stands as an anchor in the Buffalo Gap Historic Village... It is one of the best locally developed historic sites in the state. Dr. [Lee] Rode has collected such buildings as a doctor's and dentist's office, a railroad depot, a log cabin, a country church (which is used by many young people for their weddings), print shops, and barns filled with all types of western relics such as wagons.

What caught my eye when we arrived at Buffalo Gap was the collage of images that decorated the entrance to the village. There was a fading red, original Texaco sign, an old wooden archway, a cobblestone sidewalk, an iron church bell, a Texas flag, and then the few staff members who were wearing their pioneer costumes. Before I ever entered, I realized that Buffalo Gap is an oddly picturesque place.

We continued on 277 south over steep hills that several times offered and then snatched away a quick view of the mountains. We crossed Oak Creek and made our way to the site of Fort Chadbourne in the town of Bronte, "Where Livin's a Pleasure." Set on private ranch property today, Fort Chadbourne is a beautiful, secluded place to pause from the motion and hustle of the road. Buildings still standing include barracks, surgeon's quarters, a fountain house, and the ruins of the Butterfield Stage and Mail Station. The stage route started at St. Louis and Memphis and went all the way to San Francisco. It took 25 days and cost each passenger $200 for a one-way trip. For the western portion of the trip, beginning in Texas, the stage operators used mules instead of horses, as they were less desirable to the Indians. While I'm sitting in the comfort of a smooth sedan, it's nearly impossible to imagine that long, bumpy stagecoach ride.

A well-known story brings old Fort Chadbourne to life in my mind, though it is not a trail of blood but the human competitive spirit that draws us there. A few officers from Fort Chadbourne challenged the Comanches who camped nearby to a horse race, assuming that the Indians' wild-eyed mustang could be no match for the pristine Kentucky thoroughbred prized by the Texas military. Whatever the stakes, the officers paid dearly in pride as the Comanche rider not only won the race but completed the final fifty yards turned backwards, taunting the officer as he rode.

On our way out of Bronte, we drove past the historical marker for the Indian Rock Shelters, which have provided archaeologists with information about the prehistoric inhabitants of Coke County. The ancient natives used rock ledges as shelter, and they carved images into the walls of some of these caves; they left behind tools, shells, and animal bones. For thousands of years, Indian tribes dwelled in these counties that now hold the ruins of both their own primitive domiciles and the forts the Texans built to fend them off. Paradoxically, the Forts Trail links the structures that housed ancient Indians and those that defeated modern tribes. Following the Trail, we crossed Kickapoo creek and the Colorado River, near the south fork of the Concho River.

In this part of our drive we tracked a trail of blood created in 1857. In February, a company from the Second Cavalry originating at Camp Verde in present Kerr County (just 2 counties south of Fort McKavett) met Comanche raiders in a battle at Kickapoo Creek. They pursued these Indians for miles, and eventually the skirmish ended with two dead on each side. The soldiers made their way to Fort McKavett in the middle of the night, where one wounded, John Martin, died shortly after their arrival.

The military located the site for Fort Concho in 1867, at the point where the Middle Concho and North Concho rivers converge. They needed a post to replace Fort Chadbourne, which did not have an adequate supply of water. There were a few companies of black troops stationed at Fort Concho, who made great progress in mapping new routes and tracking Indians. One such company set out under the command of Captain Nicholas Nolan to apprehend raiding Indians and retrieve stolen livestock, but they experienced extreme suffering as a result. Along the Texas Forts Trail gives a description of the famous Nolan Expedition of 1877, which originated at Fort Concho in July of that year:

One of the most tragic events in Fort Concho's history occurred in the summer of 1877. On August 3, two black troopers rode into Fort Concho to report that Captain Nicholas Nolan and a detachment of black troopers, Company A, Tenth Cavalry, along with a volunteer company of buffalo hunters were lost on the plains and starving for water. Poor judgment, bad management, and indecision by the leaders resulted in the force being scattered in the desert. Some members of the group made it to water in a matter of hours, but one party of soldiers wandered for days, surviving on only the coagulated blood and heavy urine of dying horses. The majority of the expedition's members survived, but four troopers and one civilian perished, along with twenty-three horses and four mules.

To be exact, Nolan's men had gone for 86 hours without water when they finally reached Double Lakes in Lynn County, just south of Lubbock. The Tenth Cavalry, headquartered at Fort Concho, once again proved their stamina and courageous nature when they defeated Apache chieftain Victorio, and essentially rendered the Texas frontier safe once again.

While we were in San Angelo we attended Christmas at Fort Concho, an annual event that takes place on the grounds of the Fort, but it really encompasses the whole town. San Angelo has a quaint little downtown area speckled with antique shops and inviting cafes. We drove through the town square and circled it twice to get a better look. The folks here, like those in Breckenridge, wore their festive sweaters, socks, and hats, decorating the busy street corners with their array of red, white and green. At Fort Concho, the cold December weather did not keep the curious visitors from attending Christmas. Most were families with children, and we walked through tent after tent of merchandise from the frontier period. There were costumes like the gray and blue jackets and knee-length pants the men wore, there were swords and turquoise or ivory handled pocketknives. There were sheathed daggers and arrows with fur lined quivers. There was loose tobacco and there were pipes. Coins and medallions gleamed from within glass cases. Outside in the center of the fort was a large field where men in the old military uniforms of the 1850's fired cannons and shot muskets. Ladies rode sidesaddle through the grounds, donning the dignified air of those who first lived in these Texas towns, and who first patronized the shops and first swept the floors of the houses along the rivers.

We walked through the soldiers' barracks building, which had at least two dozen wooden cots with thin feather mattresses about the thickness of a warm sleeping bag. I could picture the primitive means by which these men lived as I walked across the dirt floor and past the small coal furnace in the center of the room. I remember thinking that I would hope to be one of the two lucky soldiers whose beds were right next to the heater because those beds all the way at either end surely felt no heat. There was an unlabeled bottle of a copper liquid that appeared to be whiskey lying on a small table between two beds. So that's how they kept warm.

We walked past a round pen where children mingled with sheep and goats and romped with donkeys. The soldiers set down their muskets, leaning them each against the others, bayonets crossed at the top, forming a tall metal Teepee with a sharp, shining point at the top. Here in their annual reenactments the people of San Angelo wander back to the time when messengers came thundering in on their horses to report that Nolan's men may die of thirst. Here the Butterfield Stage came through bearing weary riders to California in hopes of a fortune in gold. And here White settlers felt they could safely move into the region, inching the Comanches further westward with each passing year.

On Sunday morning, we took Highway 277 south out of San Angelo, where the Forts Trail conveyed us to Christoval, TX. We stopped for breakfast at the Country Junction, where pickups filled the parking lot to its capacity, obstructing our view of the restaurant from the street. I ate spicy sausage patties and eggs over easy while my eyes perused the walls filled with stuffed trophies of all shapes and dimensions. These were the spoils of no archer. The head of a soft-eyed deer was mounted on the wall, as well as game fowl with wings extended. Most of the patrons wore camouflage, and they ate with either the anticipation of the hunt that would follow or the hunger after the one preceding. To create some variety in the décor, the owners of the Country Junction have placed clever silhouettes of western scenes like cowboys leaning on a fence, a horse rearing back on its hind legs, or a ranch dog sitting patiently next to his companion. These solid black renderings are the work of an animator who's handy with a scroll saw. As I walked out the door I noticed three or four tiny plastic stands, each cradling the business card of a local taxidermist.

We crossed Bois D'Arc Draw along the way to El Dorado. Another name for the Osage Orange, the Bois D'Arc's wood is flexible and smooth, making it the perfect material for a handcrafted bow. The Caddo Indians made these bows, as they found the wood in abundance in East Texas, and they found that they could trade them with Indians from other regions. The Bois D'Arc hedges were thorny, and when there came to be inadequate fencing supplies for ranchers, they discovered that they could use nature as a makeshift fence. The Bois D'Arc was considered to be "pig tight, horse high, and bull strong." These thick thorny branches were the predecessors to the barbed wire fences that came soon after.

We passed through El Dorado on Highway 190 and came eventually to Fort McKavett via Farm Road 864. When such facilities are available at these forts, we usually take a little time to walk through the museum and gift shop of each. McKavett's was my favorite. There were large partitions set up through a circular corridor that told a succinct chronology of the Indian wars in paragraphs and pictures. McKavett's grounds have some ruins and a rebuilt hospital and officers' quarters, but at one time it held a vast collection of permanent buildings including two-story officers' quarters, a bakery, a laundry facility, enlisted men's barracks, a powder magazine, and a hospital. Apparently I am not alone in my opinion of this one; General Sherman executed a famous inspection tour in 1871 and named McKavett "the prettiest post in Texas."

At one time, Fort McKavett was the operating base for four regiments of black soldiers, and in a real life enactment of To Kill a Mockingbird , a local white farmer shot a black soldier and ultimately escaped punishment. John "Humpy" Jackson discovered a letter his daughter received from an enamoured black trooper. In his rage, he killed a black soldier, though not the one with whom his daughter corresponded. According to legend, the military searched two years for Jackson before he surrendered, and he was found innocent of all charges in 1871 when he went to trial.

We stayed on 190 to Menard, TX where we picked up Highway 29 into Mason. Before the town itself existed, an unfortunate resident of the Menard vicinity was captured when Kiowa chief Satanta executed a raid throughout the plains in 1864, what would become one of the bloodiest years in the tale of the Texas frontier. Dorothy Field became their captive, and they traveled with her all the way north to Kansas. There is no record of her rescue, but there is evidence that Rangers were still searching for her 10 years later.

Driving toward Menard, the archer's blood trail led us back 100 years before the time of the frontier forts to a time that was equally treacherous, when the Spanish occupied parts of Texas, some for exploration and some for religious crusade. When these proud, ambitious men arrived with horses and artillery into a brand new world, they encountered tribes of Indians who were at war with one another. In a bitter twist of fate, these weapons and horses that equipped the Spanish when they arrived fell into the grip of the Comanches, and ultimately these warriors surpassed the Spaniards in their skills on horseback and defeated them.

Believing that to embrace the Lipan Apaches and teach them Christian doctrine would be to establish peace with the Indians, the Spanish built the San Saba Mission in 1757. They chose a site bordered on one side by the San Saba River and by the Arroyo de Juan Lorenzo (now Celery Creek) on the other. The Spanish thought that this location would provide an unending supply of water while it protected them from hostile attacks. Unfortunately, they were gravely mistaken. The Creek's steep banks allowed the warriors to pass undetected into the boundaries of the Mission, and the Presidio built to protect it sat a full half-mile from the Mission itself. Colonel Diego Ortiz Parilla, who commanded the Spanish army in that area, raised objections about the vulnerable positioning of the buildings, but they did not heed his warnings.

The Spaniards' relationship with the Apaches caused enmity like they had never seen before. The Comanches and several other plains tribes attacked the San Saba Mission to find the Apaches who might reside there and leave nothing but a trail of fire and blood for those few survivors who had befriended their ancient enemies. One of these survivors, Friar Miguel Molina, recorded a detailed personal account of the events of that fateful day. Because we have access to what his eyes and ears perceived, I can imagine what transpired:

Thereupon the Father President went out into the courtyard. I accompanied him, filled with amazement and fear when I saw nothing but Indians on every hand, armed with guns and arrayed in the most horrible attire. Besides the paint on their faces, red and black, they adorned with the pelts and tails of wild beasts, wrapped around them or hanging down from their heads, as well as deer horns. Some were disguised as various kinds of animals, and some wore feather headdresses. All were armed with muskets, swords, and lances (or pikes, as they are generally called), and I noticed also that they had brought with them some youths armed with bows and arrows, doubtless to train and encourage them in their cruel and bloody way of life.

As soon as the wily enemy became aware of the confidence we placed in them, many dismounted and, without waiting for us to unlock the gates, opened them by wrenching off the crossbars with their hands. This done, they crowded into the inner stockade, as many of them as it would hold, about three hundred, a few more or less. They resorted to the stratagem of extending their arms toward our people and making gestures of civility and friendliness. When I noticed that many chieftains had approached with similar gestures, I advised and persuaded the Father President to order that they be given bundles of tobacco and other things they prize highly. This he did most generously. I myself presented four bundles to an Indian who never did dismount and whom the others acknowledged as their Great Chief. He was a Comanche, according to the barbarians themselves, and worthy of respect. His war dress and his red jacket were well decorated, after the manner of French uniforms, and he was fully armed. His face was hideous and extremely grave.

When I gave him the four bundles of tobacco, he accepted them cautiously, but with a contemptuous laugh, and gave no other sign of acknowledgment. I was disconcerted at this, all the more so because I had already seen that the Indians, heedless of their promises of peace, were stealing the kettles and utensils from the kitchen, and the capes of the soldiers. They also took the horses from the corral, and then demanded more. When they were told there were no more, they asked whether there were many horses at the Presidio. The Fathers and soldiers told them that there were indeed many horses at the Presidio, as well as equipment and supplies of all kinds-a reply we thought expedient to make them fully aware that nothing was lacking for the defense of the Presidio. When we asked the cunning enemy whether they intended to visit the Commandant at the Presidio, they replied that they did, and asked us to give them a note to him. We did not consider his request inopportune, but rather thought it might be an effective way of clearing the Mission of the enemy, for they still had it completely surrounded and were causing great damage by their thievery, as they boldly ransacked all the buildings and offices.

Desiring retaliation for the sack of the Presidio, Colonel Parilla escorted 360 Spanish soldiers and 176 Indians north toward the Red River. After fighting the Comanches and their allies for four hours, Parilla and his men had to retreat, leaving their cannon and several weapons behind. The Comanches proved their resilience and imperviousness in the events surrounding the attack on the San Saba Mission. Like a child's quest for the place where a rainbow meets the earth, conquering them and submitting them to the Spaniards' laws and religion was a lofty and fruitless endeavor. It would require another 100 years and an opponent with much more ardor and resolve to wrest the plains from their desperate grip.

Highway 29 east leads to Mason, TX, conveying its drivers through cactus-speckled mountains along the way. On the roadside, an historic marker describes Pegleg Crossing, a favorite mountain pass of Indians as well as "adventurers, mustang hunters, Indian fighters, German settlers, gold-seekers," and it became a stage station that was notorious for hold-ups. The Spanish fought Apaches here in the 1730's before they attempted peace via the construction of the Mission. We entered Mason on a Sunday's mid-afternoon, and like a magnet pulling another into its field, Santos Taqueria drew Rick's Cadillac through the town square and into its last available parking space.

It is worth mentioning here that a secondary goal (or even tertiary and beyond), for what we have now come to learn classifies us as Heritage Tourists, has evolved in the mere practice of our embarking on these road trips and also in our necessity for sustenance that is both repeated daily and unrelenting. The goal has become of course to find the best and most authentic Mexican food. While it takes quite the back seat to the enterprise of finding and revealing the places where blood was shed for possession of the land where we can now safely and freely roam, this is no small task, and it is not to be taken lightly. There is, I have found, some correlation between the caliber of the food and the décor of the place in question. In the places where the food is unquestionably authentic, the common denominator appears to be an exuberant prominence of the color red. It might anger the bulls down there, but in these parts the plastic red roses; red velvet curtains, carpet, and cloth napkins; and the paintings depicting the red ruffled tiers of the ladies' skirts are a sure sign of great food ahead. Another sure way to determine whether or not a place will make the list is that part or all of the menu is written in Spanish. In these cases, you can order by number, and selection 1 all the way to 43 is certain to be a hit. One note: those more adventurous or more carnivorous may want to try the Tacos con Lengua , but I usually stick with pollo .

When I walked into Santos and looked around, I immediately subjected it to the criteria formed by our past experiences, and I was a little unsure. The restaurant was minimally decorated in earth tones with several pieces of southwestern style pottery. The menu, printed on a giant sign on the wall over the heads of two longhaired young men who served as both cook and cashier, looked like the menu in a college campus sandwich shop. We ordered at the counter and grabbed a table after pouring some of the homemade salsa out of a pitcher into paper cups. While we waited for the food, I noticed T-shirts and sweatshirts for sale, bearing the Santos Taqueria logo and costing about $20 a piece. It turns out that the food was unbelievably excellent, and we were both shocked to have our expectations so remarkably surpassed. Santos made the list, and Mason, TX became for me a place worth a longer look.

We drove outside of town up a steep hill where a reproduction of Fort Mason's barracks now stands. It was originally built in 1851 strategically positioned on Post Hill, providing an incomparable vantage point. In written descriptions of the fort, nearly all its visitors commented on the view from the top of the hill. I too wouldn't mind being the owner of that land-- the fort's one remaining building sits proudly above the rest of the town, and a Texas flag waves farewell to those descending and beckons those approaching. Robert E. Lee commanded troops who were stationed here before his more famous role in the Civil War. Fort Mason also served as a prison camp for Union sympathizers for a short time. However, Santos Taqueria and the climb to the top of Post Hill are only two of the treasures tucked neatly inside Mason, TX. It is also the only location in the lone star state where topaz exists, buried deep in the soil in ravines and creek beds. Two ranches in Mason County allow people to dig for Texas' state stone for a reasonable fee. You can camp at night and become a hunter by day, sifting dirt through mesh screens for the rocks that gleam rich gold or pale blue.

The Forts Trail follows Highway 386 north, then 71 west to Brady, called the Heart of Texas for its location at the geographical center of the state. It's hard to miss evidence of Brady residents' pride in this claim to fame as you pass such places as the Heart of Texas Bed & Breakfast and the Country Music Museum. There is the cleverly named Hard 8 Barbecue Restaurant depicting a pair of dice, each showing a four, and an eight-point buck. The Trail weaves through town and comes out on Highway 190 eastbound. Along 190 we passed two historical markers within half a mile of one another. The first describes the Historic Soldiers' Water Hole, where Robert E. Lee led his troops to water when they were in the vicinity scouting for marauding Indians. Immigrants camped nearby as well, using this location to revive their tired, thirsty families while they made the difficult trek westward. Twenty-seven Indians attacked one such group of 18 men, women, and children in 1850. They murdered the families and stole their horses. A little further lies the site for the 1866 Onion Creek Indian Fight, where the whites retrieved stolen horses from an Indian camp. An arrow struck one of these men in the head, and certainly against all medical odds, they removed the arrowhead with a pocketknife, and he survived the injury. What a larger than life story he must have told his grandchildren!

We continued along the Forts Trail, turning north onto Highway 45 at the town of Richland Springs. There were bloody incidents around this town in the 1850's and a few witnesses lived to pass the stories on. Our drive from Brady to Richland Springs traces the path that a posse from Richland Creek took when they pursued a band of Indians who murdered Beardy Hall. In an eye-for-an-eye fashion, they killed one Indian and gave his scalp to Hall's son Alex, who displayed it on a fence post for quite a while.

In Richland Springs, there was an unofficial fort privately owned and located on the Duncan brothers' ranch. There, families "forted up" when threats of Indians were imminent. In 1858, a company of rangers camped near the location of the old Fort Duncan, and they sent two men out to scout a path through which to take their wagons. Indians attacked, and the men ran back to camp. To the great consternation of the Indians, I'm sure, the Ranger Company outnumbered them, so a running fight ensued, and the Rangers killed four and recovered several stolen horses.

Like a vicious game of volleyball, back and forth the depredations go. One, two, even three in a row for the Indians, then a few lives and horses taken back by the whites. In blood and tears they fill their scorecards until eventually and inevitably someone gets the victory. The frontier forts are all connected on this drive by the highways that lead to them and the towns that developed because of them. But, having seen the ruins, and heard the muskets fired at Fort Concho's Christmas, and passed the forks and creeks where individuals ripped arrow heads from underneath their skin, it is more realistic for me to visualize the route as a crimson trail of blood. It only requires a look backward in time and a reliable sedan, an archer's stance with feet planted wide, a tight elbow and the steady pull of the bow.

Blood Trails through the Cross Timbers.

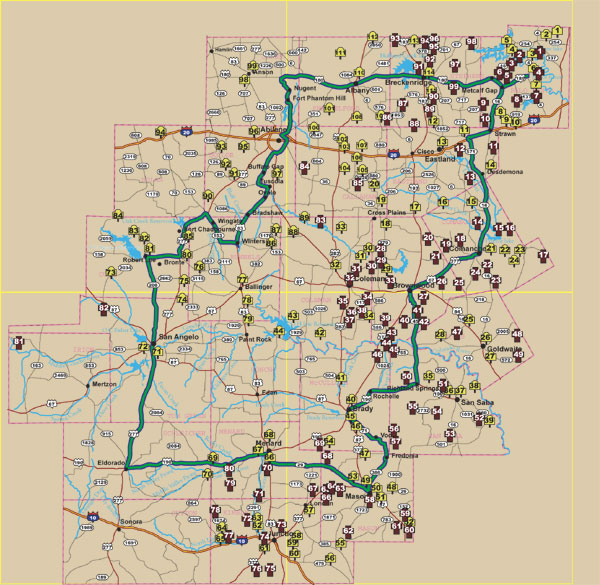

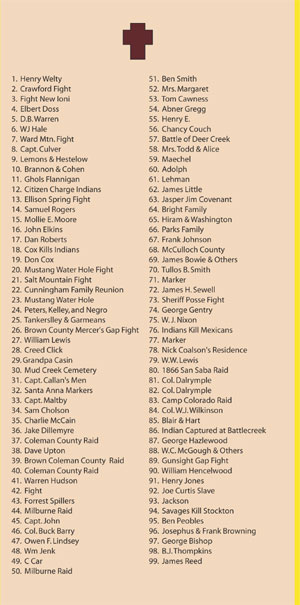

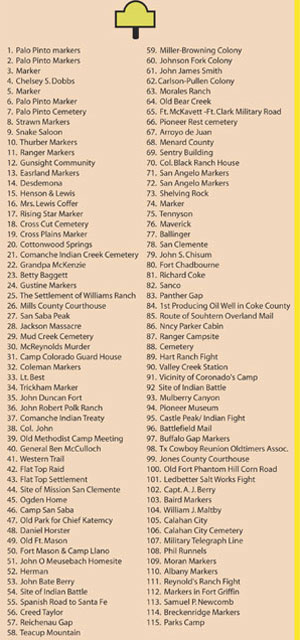

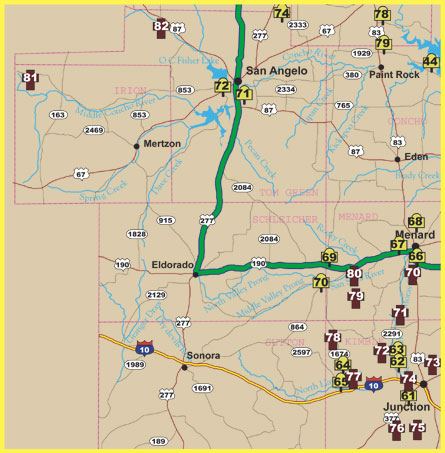

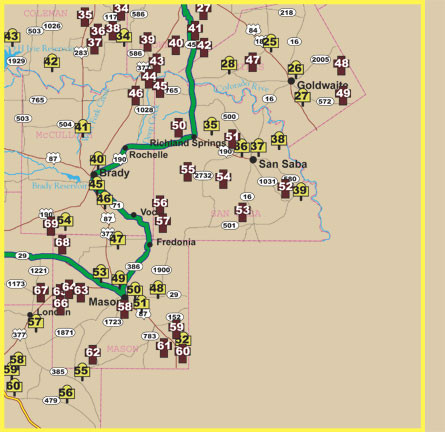

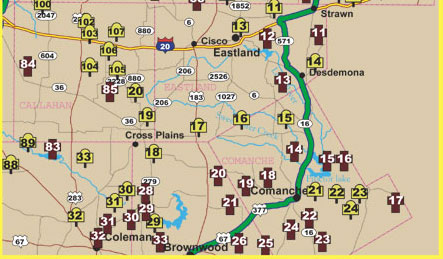

Additional maps and information related to this drive

Texas Historical Commission Fort Trail Division

Home | Table of Contents | Forts | Road Trip Maps | Blood Trail Maps | Links | PX and Library | Contact Us | Mail Bag | Search | Intro | Upcoming Events | Reader's Road Trips Fort Tours Systems - Founded by Rick Steed |