San Gabriel Blood Trail (4) |

|

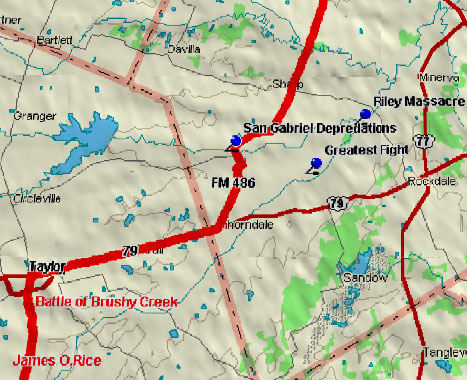

Marker Title: James O. Rice

Address: North from SH 290 11.3 miles to FM 1660/FM 973 intersection,

8 mi. S of Taylor on FM 973.

City: Taylor

County: Williamson

Year Marker Erected: 1977

Marker Location: Intersection of FM 1660 and FM 973, 8

mi. S, Taylor

Marker Text: (1815 - about 1875) South Carolina-born James

O. Rice migrated to Texas by 1835 and served in the Texas Army during

the War for Independence. In early days of the Republic of Texas, he

protected frontier settlements as part of a Texas Ranger company. On

May 17, 1839, in command of a volunteer force clashing with Mexican

troops led by Manuel Flores on the North San Gabriel River, Rice captured

vitally important documents related to the Cordova Rebellion against

the Republic of Texas. He joined the Somervell and Mier Expeditions

of 1842 and the Snively Expedition of 1843. He also served in the Mexican

War (1846-48). For military services, he received several bounties of

land. When Williamson County was created in 1848, Rice was one of the

commissioners named to select a site for the county seat. One of the

county's largest landowners, Rice built his home on Brushy Creek about

one mile west of here at a site then known as Blue Hill and later called

Rice's Crossing. He ran a store and was postmaster of Blue Hill post

office, 1849-57. For a short time, he had a tanyard in Georgetown. Rice

married Nancy D. Gilliland (d. 1860), of an early Texas family. The

couple had four daughters. Rice is buried in the Sneed Family Cemetery

near Austin. Rice, Flores Fight at the San Gabriel, May 17, 1839

Marker Title: Battle of Brushy Creek

Address: 4 mi. S on SH 95

City: Taylor

County: Williamson

Year Marker Erected: 1993

Marker Location: 4 mi. S of Taylor on SH 95, then W on

gravel road

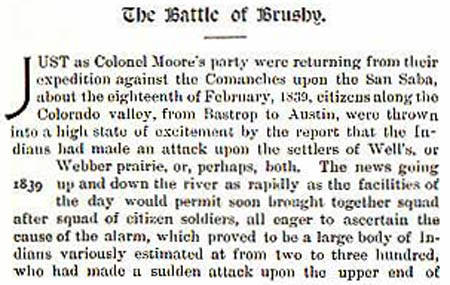

Marker Text: A skirmish between Comanche raiders and a

local militia near here in mid-winter (1839) led to the last major battle

between Anglo settlers and Indians in Williamson County. The Comanche

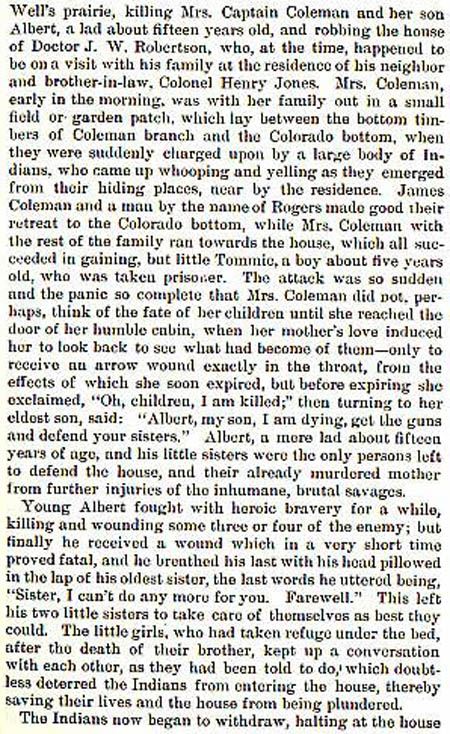

retaliated on February 18, 1939, by attacking several area homes, including

those of Mrs. Robert and Dr. J. W. Robertson. Mrs. Coleman and her son,

Albert, were killed. Another son, Tommy, and seven of Robertson's slaves

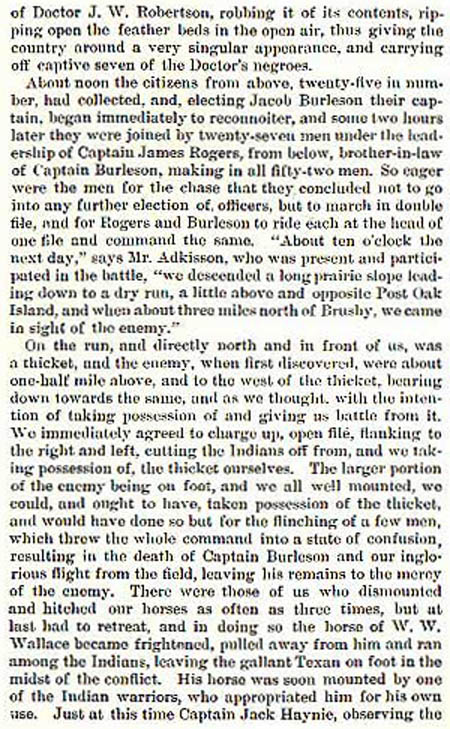

were taken captive. The ensuing battle along nearby Brushy Creek claimed

the lives of Jacob Burleson, Edward Blakely, the Rev. James Gilleland,

and John B. Walters.

The above story of the Battle of Brushy Creek is from the book Indian Depredations in Texas by J.W. Wilbarger.

February 25th, 8-1/2 miles off of the mouth of Brushy Creek off the

Brazos. There was a party of ten led by surveyor Thomas A. Graves that

was attacked by more than one hundred Indians. Two were killed including

James Drake and two others wounded.

Graves led his men in a retreat to their raft on the Little River.

Bernard Holtzclaw narrowly escaped injury when a bullet passed through

his pantaloons.

Two days after the attack, Graves wrote a letter to Sterling Robertson

from the Little River:

I suppose from appearances there could not have been less than one

hundred. I had pitched my tent cloth in the open post oak timber within

eight miles and a half of the mouth of Brushy Creek and having made

[no] particular discovery of Indian sign previously, we laid down

carelessly as we had done before; and on Friday morning a little before

daylight they charged up within twenty paces and discharged 15 or

18 guns and killed two of the company and wounded two others.

During late September, surveyor Thomas A. Graves set out from Bastrop

in Robertson's Colony with a party of seventeen land surveyors and

speculators. After surveying ten leagues near the San Gabriel River,

one of the small groups of surveyors was attacked by a party of Indians.

An Irishman named Lang was killed and scalped while working his compass.

One of the men of the party of four escaped and ran to the men under

Graves to spread the news. The other two men being unaccounted for,

the men under Graves decided to go in search of them.

One of Graves' surveyors was George Erath, who had joined his surveying

party after serving in the Moore expedition through August 28. Erath

felt that "there was little danger in our whole party remaining

a few days longer," as the Indians were believed to have fled

after lifting their scalps. Graves' men went to the scene of the attack

but didn't find any bodies. The Indian attack was enough to cut short

this surveying trip, as Erath recalled:

We paused there and, after another deliberation, Graves cut the

matter short by declaring he had fitted out the expedition, would

have to pay the hands, and did not propose to be at unnecessary

expense in public service. So we turned back. Had we gone but a

few hundred yards farther we would have found Lang's body.

Before returning to Bastrop, Graves' surveying party did find two

other badly frightened survivors of this Indian depredation.

Graves, Erath, and the other surveyors returned from their expedition

early in October and made town at Hornsby's settlement. There, they

found events that would forever change the future of Texas had occurred

in their absence.

January 1836, Thomas and James Riley were attacked by a band of forty

Caddos and Comanches. Thomas was killed and his brother was severely

wounded but survived. Stephen L. Moore describes in his book,

Savage Frontier, how the Riley depredation caused the formation

of Sterling Clack Robinson's Ranger company in January, 1836.

This event happened along the upper tributaries of the Little River,

a hunting grounds the Indians called "Teha Lanna" or "the

Land of Beauty." The pioneers they attacked were brothers James

and Thomas Riley, who were traveling with two loaded wagons and

their wives, children, and another young man.

Near the mouth of Brushy Creek on the San Gabriel River, the Rileys

met surveyor William Crain Sparks and his servant Jack. These three

were returning from Sparks' camp near the Little River, where they

had encountered Indians. Sparks and Jack Had set out from Tenoxtitlan

with a man named Michael Reed and an ox wagon loaded with corn.

As dusk fell on their camp on the Little River, Reed crossed the

river to visit the camp of newly arrived emigrant John Welsh. During

his absence, Indians attacked the camp of Sparks and Jack, who both

hid in a thicket.

Sparks and Jack survived then set out after morning for Tenoxtitlan.

En route, near where Brushy Creek met the San Gabriel, these two

happened upon the Rileys. They advised the Rileys to turn back,

but their warning was not heeded. Within another mile the Rileys

encountered a band of about forty Caddos and Comanches. The Indians

claimed to be friendly and stated that they were only following

Sparks and his black man.

The Riley party decided to turn back at this point, but the Indians

attacked them just as they reached the Brushy Creek bottom. One

of the Indians leaped onto the lead wagon horse and cut loose the

harness. Before he could strike, one of the Riley men shot him dead

and thus started the general fight. Thomas Riley managed to kill

two Indians before being mortally wounded himself. James Riley also

killed two of his attackers but was severely wounded in four places

before the remaining Indians fled.

The younger man accompanying the Rileys fled with the women and

children during the engagement. They reached the settlements on

the Brazos safely within two days. The seriously wounded James Riley

laid his brother Thomas's body on a mattress and wrapped it before

mounting a horse and heading for Yellow Prairie in present Burleson

County. After reaching safety the next day, he returned with a party

to bury his brother.

Riley survived with severe wounds that kept him confined for a

long period of time. A petition was presented to the Congress of

Texas in 1840 for the republic to provide aid to the crippled James

Riley in supporting his wife and six children.

Empresario Sterling Clack Robertson organized a ranger company

to defend the citizens of his colony. The unit's muster roll shows

that they were mustered into service on January 17, 1836. The Riley

death was reported in the January 23 issue of the Telegraph and

Texas Register, noting that the Indians had taken eight of the

Riley's horses. The paper reported that a company of twenty-five

men had gone immediately in pursuit of the Indians. This number

obviously increased as more men joined Robertson's company, for

his muster roll, signed by Robertson as "Captain Rangers,"

shows a total of sixty-five men.

Among the members of the company was Elijah Sterling Clack Robertson,

the fifteen-year old son of the captain. The company also included

rangers who had recently served under Captains Daniel Friar and

Eli Seale. Friar's reduced company remained in service throughout

January, although at least eight of his men had enlisted in Robertson's

new company.

Robertson's company had returned back to town by January 26, on which

date empresario Robertson was conducting colony business. It is unknown

exactly how long Robertson's ranger company remained in service, but

it was disbanded by late February. Sterling Robertson was elected to

the Convention of March 1 on February 1. Correspondence of Captain Robertson

further places him at Milam as of February 7 and at the Falls of the

Brazos as of February 18.

* items are taken directly from the book, Savage

Frontier, by Stephen L. Moore. |