Rangers

The early Republic of Texas Rangers Organization was based on the English tradition of the rural sheriff riding or ranging across his jurisdiction to administer justice and keep the peace. They were further influenced by Roger's rangers, formed during the French/Indian war and Clark's rangers during the Revolutionary wars. Made up of volunteers (usually Scots/Irish frontiersmen), they elected their captains and specialized in quickly covering long distances and delivering hard-hitting surprise attacks. The modern U.S. Army still maintains an elite Ranger Corp whose training includes Roger's ranger manual.

The Texas Rangers

From the time that Texas became a republic, up until the present day, the rangers have played a prominent part in the history of our state, and invariably waged an effective war against the wild Indian tribes. While the Federal government was making preparations to wage an aggressive campaign against the hostile Indians, the state government, which had for many years furnished Texas troops to protect the frontier citizens, took active steps to, also, wage a more aggressive campaign. As a consequence, on the 10th of April, 1874, the Legislature passed an act, among other things, providing that the governor be required to organize, or cause the same to be done, one company of not less than twenty-five, nor more than seventy-five men for each county that may be subjected to invasions of Indians, outlaws, and others. This act further provided that the governor also cause to be mobilized a battalion of mounted men to consist of six companies of seventy-five men each; that the battalions be under the command of a major, and that each company should have one captain, two lieutenants, and one quartermaster, and other inferior officers. The salary of the major was placed at $125.00; captain's, $100.00; lieutenant's, $75.00; sergeant's, $50.00; and non-commissioned officers and privates, $40.00. This act was an amendment of other acts previously passed. The battalion was placed under the comand of Major John B. Jones. One of his companies, which headquartered in Jack County, was headed by Capt. Stephens. Another, located in Palo Pinto County, and for a time camped near the Flat Rock Crossing in Dark Valley was commanded by Capt. W.C. McAdams, an old experienced Indian fighter. Still another company saw action in Menard County, and elsewhere, and was commanded by Rufe Perry. Capt. W.G. Maltby had charge of another, stationed in Brown County, and Capt. Ikard and Capt. Caldwell were in command of companies further down the line. This battalion waged an aggressive campaign and rendered very effective service towards suppressing Indian depredations along the frontier. Ref: Author dug into old reports and documents on file in the Adjutant Generals office in Austin; referred to early Statutes, etc.

The above story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

Major Robert Rogers. From the John Carter Brown Library

Rangers suffered early defeats against well-mounted Plains tribes, such as the tragedy at Stone Houses fought just north of Cottonwood Springs. That same year, 1837, and a little further south in the Palo Pinto Mountains, Texas Ranger Big Foot Wallace was captured and adopted by Comanches. He eventually escaped, rejoining his Ranger Company just about the time its captain, Jack Hays, developed a winning combination of thoroughbreds and repeating Colt pistols.

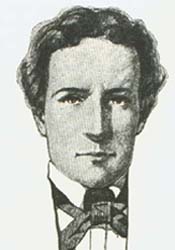

Sam Walker

Capt. Hays sent this Ranger to see the gun maker, Colt, in New York about making a heavier forty-five caliber six shooter for the Rangers.

(Photo from the book, The Texas Rangers, by Walter Prescott Webb)

Aided by Apache scouts, these Rangers could finally take the fight to the Comanches. They found they not only had the ability but the advantage in the high speed and knee to stirrup brand of combat perfected by the Comanches. East Texas Ranger companies depended more on axes and rifles as they fought their way through thick forest.

Indian Actions

The following is from the book, Savage Frontier II, by Stephen L. Moore:

Rangers in colonial Texas raised posses to punish or drive out renegade Indian tribes. The Republic organized Ranger Companies to perform this duty but there were several bitter defeats when they first tried to pursue the tribes upon the plains, such as the Battle of Stone Houses. Ranger victories allowed the Republic to expand west as Captain Jack Hays successfully led his men, including Big Foot Wallace, far beyond the Colorado River, deep into Comancheria. East Texas Ranger Companies fought their way up the Trinity and the Brazos, expanding the Republic to the site of modern-day Fort Worth under the treaty of Bird's Fort.

Following statehood, Ranger companies were called into service of the United States in its war with Mexico, and much of the credit for the victory belongs to the Rangers.

When the United States built a western line of forts to protect the migrating gold seekers, the soldiers and the action moved one hundred miles west to Fort Belknap, the frontier's new hot spot. Reservations were established for the Indians, and the cream of America's military talent rode onto the North Texas frontier with the Second Cavalry. Rip Ford was authorized to form a Ranger battalion to protect the frontier and the Texas Indian Reservations when the Second Cavalry was relocated to Utah. Important Ranger battles were fought at Antelope Hills and the Pease River before Texas joined the Confederates. Captain Barry and Captain Cureton's Rangers were stretched thin, and the frontier suffered devastating Indian attacks particularly the Elm Creek Raid. Capt. Ira Graves led a bunch of cowboys in the bloody Salt Creek Fight. Ranger Companies continued to operate out of Decatur headquarters long after the U.S. Army returned to the frontier. The Indians remained a very dangerous threat as proven by A.J. Sowell's account of his company's 1871 fight at the Keep Ranch. A few years later, Major Jones formed the Rangers' frontier regiment. His company's 1874 defeat at Lost Valley during Lone Wolf's Revenge Raid proved the frontier would remain a deadly place until the raiding Indians were completely defeated, however, a year or so later when all the Indians had surrendered, Jones found out his men would stay busy just the same.

Jones reports frontier conditions, 1874:

Besides…scouting for Indians, the battalion has rendered much service to the frontier people by breaking up bands of outlaws and desperadoes who had established themselves in these thirty settled Counties [patrolled by the Rangers], where they could depredate upon the property of good citizens, secure from arrest by the ordinary process of law, and by arresting and turning over to the proper civil authorities many cattle and horse thieves, and other fugitives from justice…

Although the force is too small and the appropriation insufficient to give anything like adequate protection to so large a territory, the people seem to think we have rendered valuable service to them, and there is a degree of security felt in the frontier counties, that has not been exhibited [or] experienced for years before. CMR

The Rangers had a reputation for their brave service, but also for their wild, reckless spirit when they were off duty. The following description of the town of Jacksboro, from the book History of Jack County by Thomas F. Horton, portrays the part the Rangers played in the disorderly nightlife:

On the south side of town was a huge military post, Fort Richardson, which had a horde of heavy drinkers and hell-raisers; on the north side of town was a camp of Texas Rangers who got pretty wild when they came to town; all of the cowboys let off steam when they got to town; stir in a bunch of buffalo hunters, government freighters, and saloon girls; and mister, we had a "Red Hot Town."

There were frequent shoot-outs on the streets of Jacksboro. Some of the saloons had fiddle and accordian players that played and sang all night long. When the soldiers got paid at Fort Richardson, it wasn't safe on the streets for 2 or 3 days. Jacksboro was in dire need of law and order.

The Texas Rangers were and continue to be an

inspiration for comic book, movie and television dramas.

(Photo from the book, The Men Who Wear The Star, by Charles M. Robinson, III)

Ranger stories from the book, Texas Ranger Tales, Stories That Need Telling, by Mike Cox:

Back in Texas on September 9, 1843, after escaping from Mexican custody along with two other Texans-including the man who would one day deliver his eulogy-Walker soon signed up to ride with the legendary Ranger Captain John Coffee Hays. In the words of a contemporary writer, Texas was "then embroiled with the abrasions of the great Camanche [Comanche] race and the minor tribes strewn along her northern frontier." Mindful of these "abrasions," in January 1844 the Congress of the Republic of Texas authorized Hays to organize "a Company of Mounted Gun-men, to act as Rangers."

Hays recruited his men in February and March and went to work on the frontier. All the Rangers were armed with a new weapon, originally purchased by the Republic for its navy: a five-shot revolver manufactured by a Connecticut gunsmith named Samuel Colt. Walker and the other Rangers soon got a chance to use the new pistols.

On June 8, 1844, near a creek in the Pedernales River watershed, at a point Hays later described as about fifty miles north of Seguin (no other communities existed in the area at the time), the Rangers-including Walker-tangled with seventy to eighty Comanche and Waco Indians. Hays reported some Mexicans also were in the party.

This is how Hays described the fight in his official report:

After ascertaining that they could not decoy or lead me astray, they came out boldly, formed themselves, and dared us to fight. I then ordered a charge; and, after discharging our rifles, closed in with them, hand to hand, with my five-shooting pistols, which did good execution. Had it not been for them, I doubt what the consequences would have been. I cannot recommend these arms too highly.

The Rangers killed twenty-three of the hostiles, badly wounding another thirty. Hays lost one Ranger to Indian arrows with Walker, Robert Addison Gillespie, and another Ranger suffering wounds.

Walker later assessed the fight in this light:

Col. J.C. Hays with 15 men fought about 80 Comanche Indians, boldly attacking them upon their own ground, killing and wounding about half their number. Up to this time these daring Indians had always supposed themselves superior to us, man to man, on horse…the result of this engagement was such as to intimidate them and enable us to treat with them.

This battle changed the history of the West. It marked the first time Rangers had been able to fight the Comanches with an effective close range weapon that did not have to be reloaded after each shot. In firing an estimated 150 rounds, Hays and his men shot 53 Comanches in a running battle. The Rangers had the frontier equivalent of the atomic bomb on their side.

The Comanches, though clearly at a disadvantage in weaponry, still were extremely competent in using their bows and arrows and lances.

"In this encounter," Graham's Magazine reported only a few years later, "Walker was wounded by a lance, and left by his adversary pinned to the ground. After remaining in this position for a long time, he was rescued by his companions when the fight was over."

Walker was taken to San Antonio, where he recovered from his wounds. Despite his close call, Walker stayed with Hays until the Ranger company ran out of funding. In 1845 he served in another Ranger company, this one led by Gillespie. On March 28, 1846, Walker was honorably discharged from the "Texas Mounted Rangers." But more rangering lay ahead.

Another story from the book, Texas Ranger Tales, Stories That Need Telling, by Mike Cox:

Former Ranger A.J. Sowell remembered years after his Indian-chasing days an occasion when his company, sixty miles into the frontier beyond Fort Griffin, was running low of the essentials-flour, bacon, coffee, and tobacco. Not only that, an icy norther was blowing and the Rangers only had two tents. On top of all that, it was Sowell's turn to stand guard, hungry and cold, while the other men tried to sleep.

As Sowell sat alone in the cold, his rifle about to freeze to his hands, "It seemed as if all the coyotes and wolves that roamed these vast solitudes had collected, and taken their position on the hills around our camp, to serenade us with dismal howls and yelps."

Sowell did not write whether he thought about shooting some of the coyotes for breakfast, but it would be a violation of orders to shoot at one at night. The other Rangers might think Indians were attacking and that could be more dangerous than an empty stomach.

Having some fresh coyote meat would not have done much good in this case. The Ranger did not have any firewood, either.

"Without wood; our provisions nearly exhausted; with no chance of getting any, unless we could eat coyotes, we were in a sad fix. Coyotes by the million," Sowell wrote.

The Rangers turned to head back to Fort Griffin, but it took another couple of cold, hungry days to reach the fort. At their next camping spot they did find wood for a fire and grass for their horses, but no game. They were living on coffee and half-rations of bacon. By the time they set up camp near Fort Griffin, they were not far from the point of cooking some coyote when a detail of Rangers rode in to the fort to get some fresh supplies.

|