Plum Creek Leg

To the north are the beautiful counties of Comal

and Hays.

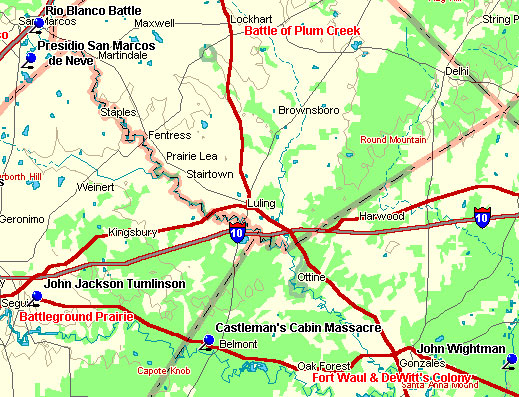

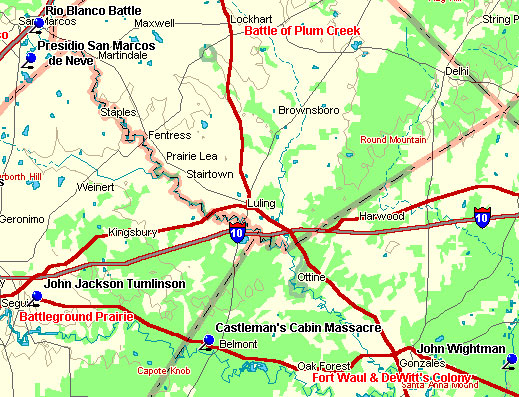

Marker Title: Battle of Plum Creek

City: Lockhart

County: Caldwell

Year Marker Erected: 1978

Marker Location: near intersection of US 183 and SH 142 in Lions

Park.

Marker Text: The harsh anti-Indian policies of President Mirabeau

B. Lamar and Mexican efforts to weaken the Republic of Texas stirred

Indian hostilities. Hatred increased after the Council House Fight in

San Antonio, March 19, 1840, where 12 Comanche chief were killed. After

regrouping and making plans for revenge, 600 Comanches and Kiowas, including

women and children, moved across central Texas in early August. They

raided Victoria and Linnville (120 mi. SE), a prosperous seaport. About

200 Texans met at Good's Crossing on Plum Creek under Major-General

Felix Huston (1800-1857) to stop the Indians. Adorned with their plunder

from Linnville, the war party stretched for miles across the prairie.

The Battle of Plum Creek, August 12, 1840, began on Comanche Flats (5.5

mi. SE) and proceeded to Kelley springs (2.5 mi. SW), with skirmishes

as far as present San Marcos and Kyle. Mathew Caldwell (1798-1842),

for whom Caldwell County was named, was injured in the Council House

fight but took part in this battle. Volunteers under Edward Burleson

(1793-1851) included 13 Tonkawa Indians, marked as Texan allies by white

armbands. Texan casualties were light while the Indians lost over 80

chiefs and warriors. This battle ended the Comanche penetration of settled

portions of Texas. More

One of the little settlements that would remain a centerpiece for

Indian troubles and revolution was Gonzales, the capital of Green

DeWitt's young Texas colony. The area of DeWitt's Colony as contracted

with the Mexican government included all of present Gonzales, Caldwell,

Guadalupe, and DeWitt Counties and portions of Lavaca, Wilson, and

Karnes Counties.

The peace in this area was shattered on July 2, 1826, when a party

of Indians attacked a group of pioneers, stealing their horses and

personal effects. Bazil Durbin was wounded by a rifle ball that drove

so deeply into his shoulder that it remained there for the next thirty-two

years of his life. The Indians next plundered the double log home

of James Kerr, where John Wightman had been left alone in charge of

the premises. Wightman was killed, mutilated, and had his scalp removed

by the Indians. The fear spread by this depredation was enough to

prevent the Gonzales area from being permanently settled again until

the spring of 1828.

Marker Title: Fort Waul

City: Gonzales

County: Gonzales

Year Marker Erected: 1988

Marker Location: US 183 R.O.W, .25 miles N of US 183 & 90

A Intersection.

Marker Text: Named for Confederate General Thomas N. Waul, Fort

Waul was built to defend inland Texas from possible Federal advances

up the Guadalupe River from the Gulf of Mexico, as well as to provide

protection for military supply trains. Construction of the earthen fortification

was overseen by Col. Albert Miller Lea, Confederate army engineer. Begun

in late 1863, the fort was partly built by slave labor and measured

approximately 250 by 750 feet. Surviving records do not indicate whether

the fort was ever actually completed.

Marker Title: Kerr's Settlement

City: Gonzales

County: Gonzales

Year Marker Erected: 1964

Marker Location: FM 146 W side of Kerr Creek, near E. city limits,

(in gazebo structure)

Marker Text: --

15 mi. W of Gonzales April 15th, 1835. From the book, Savage

Frontier, by Stephen L. Moore:

The campground was ominously quiet as the first rays of sunlight

filtered through the trees along Sandies Creek. The dawn air was cool

on the mid-April morning in South Texas. The tranquility was violently

interrupted by the sudden report of rifles and resounding war whoops

as more than sixty Comanche Indians descended on the scene.

The men of the camp scrambled to make a stand. Improvising breastworks

of carts, packsaddles, and trading goods, the besieged fired back

at the howling Indians who outnumbered them by upwards of six to one.

The contest was fierce, but it was over before it had begun.

From a small porthole type window in his pioneer cabin several hundred

yards away, John Castleman could only watch the massacre in anguish.

He was frustrated that he could not assist the besieged and that they

had not heeded his advice.

His gut instinct was to open fire with his rifle, however futile

the effort may prove to be. Only the pleading of Castleman's wife

restrained him. The first shot he fired would only ensure that he,

his wife, and his children would also be slaughtered. Even still,

it was difficult to watch as others died before him.

Castleman and his pioneer family had become bystanders to a bloody

Indian depredation in south central Texas. It was April 1835 when

the Indians descended near his place and slaughtered a party of traders.

John Castleman, a backwoodsman from Missouri, had settled with his

wife, four children, and his wife's mother in the autumn of 1833 fifteen

miles west of Gonzales. His cabin often served as a place of refuge

for travelers moving down the San Antonio Road from Gonzales. Castleman's

place was located in present Gonzales on Sandies Creek, a good watering

hole. Indians were known to be about the area, and they had even killed

his four dogs in one attempt to steal Castleman's horses.

...The traders declined the offer to use Castleman's cabin, choosing

to retire for the night near the waterhole. The Indians attacked these

traders right at daylight, the yelling from which had awakened Castleman.

The traders fired back and continued to hold their ground for some

four hours while the Indians circled them. The attackers slowly tightened

their circle as the morning sun rose, falling back temporarily whenever

the traders managed to inflict damage on their own numbers.

The traders suffered losses and drew to a desperate point. The furious

Comanches finally took advantage of their enemies' desperation and

made an all-out onslaught from three sides. They succeeded in drawing

the fire of the party simultaneously and left them momentarily unloaded.

During this brief instant, the Indians rushed in with victorious war

whoops and fell upon the traders in hand-to-hand combat.

Raiding to acquire fine stock and other goods became a ruthless sport

to the Comanche (translatable as "the real people" in Indian

tongue) as settlement of Texas began to encroach upon the hunting

lands the Indians had long claimed. By 1830 the Indian population

in the territory of Texas was perhaps fifteen thousand compared to

about seventeen thousand settlers of Anglo-European, Mexican national,

and black origin. In combat with early settlers, the Comanche warriors

had learned to exploit any advantage a battle might offer them, such

as lengthy time required to reload weapons in the case of the French

and Mexican traders. The determined Indians could accurately fire

a half dozen arrows in the time it took an opponent to reload his

rifle a single time. The battlewise Comanches forced the traders to

discharge all their weapons at once before moving in to slaughter

the men before they could reload.

This last terrific charge was witnessed by Castleman from his window,

and he immediately realized that it was all over for the poor traders.

The victims were brutally mutilated and scalped. The Comanches stayed

long enough to dispose of their own dead, round up the traders' mules,

and collect all of the booty that was desired. As they slowly rode

past his house single file, Castleman counted eighty surviving warriors,

each shaking his shield or lance at the house as they passed.

|

|

|

Col. Edward Burleson |

James Milford Day |

James Wilson Nichols |

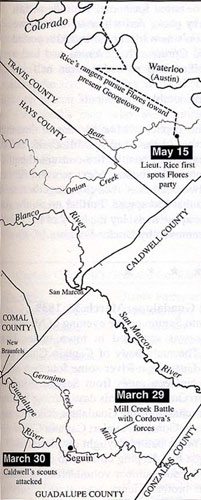

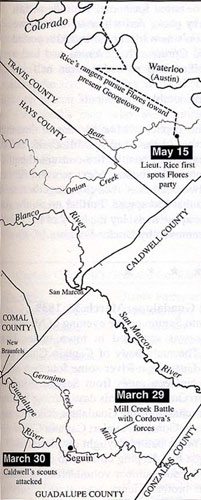

James Milford Day, pictured above, one of Guadalupe County's earliest settlers, was seriously wounded in a gun battle with Cordova's rebels on March 30, 1839.

Ranger Jim Nichols, also above, wrote of Day's suffering:

We taken them home but Milford had a lingering hard and painful time before he recovered, and after he was thought to be well his hip rose and several pieces of bone worked out. Then for many years he had to undergo the same pain and suffering from his hip rising and pieces of slivered bones working out. He finally recovered after years of pain and suffering, but it made a cripple of him for life. But he is still living at this writing and limping around on one short leg and has seen as many ups and down since that time as any man of his age.

Marker Title: Battleground Prairie

City: Seguin

County: Guadalupe

Year Marker Erected: 1936

Marker Location: from Seguin, take US 90A East five miles to

marker site.

Marker Text: Where 80 volunteers commanded by General Edward

Burleson defeated Vicente Cordova and 75 Mexicans, Indians and Negroes,

March 29, 1839, and drove them from Texas, ending the "Cordova

Rebellion." 25 of the enemy were killed. Many volunteers were wounded,

but none fatally.

John Jackson Tumlinson, who had requested the need for a ranger-type

system in January 182, was killed on July 6, 1823, by a band of Indians

near the present town of Seguin in the Colorado settlement. Tumlinson

and a companion, aide Joseph Newman, had been en route to San Antonio

to secure ammunition requested by Moses Morrison's men when he was

killed by Karankawa and Huaco Indians.

John Jackson Tumlinson's son, John Jackson Tumlinson Jr., later a

respected ranger captain, collected a posse and led them against a

band of thirteen Huaco (Waco) Indians who had camped above the present

town of Columbus. The posse leader's teenage brother, Joseph Tumlinson,

acted as a scout for this unit and managed to kill the first Indian

when the Texans surprised the Waco camp. Captain Tumlinson's posse

killed all but one of the Indians.

Presidio San Marcos de Neve was founded in the early nineteenth century

four miles below present-day San Marcos, where the Old San Antonio Road

crossed the San Marcos River. A flood in June of 1808 nearly wiped out

the community. The colony held on for several years, but harassment

by Comanche and Tonkawa Indians forced settlers to abandon it in 1812.

Archeologists recently have discovered ruins, which are probably of

the presidio and community. The location of these ruins is still being

kept a secret.

Castleman gathered his family and hurried to Gonzales where volunteers

were raised for pursuit. Just outside of San Marcos on bluff of Blanco

River, April 18th, 1835, Captain Bartlett D. McClure's posse of about

thirty men found the murderers. The posse split into two parties, one

circling around while the other attacked. John Castleman was among those

who killed a few warriors during the advance. Andrew Sowell Sr. was

part of the group of volunteers waiting behind the Indians in ambush.

His nephew, A.J. Sowell, later wrote:

Several shots were fired, and a third Indian had his bow stick shot

in two while in the act of discharging an arrow. Andrew Sowell attempted

to fire with a flintlock rifle, but it flashed in the pan. He had

stopped up the touch-hole to keep the powder dry in the fog, and had

forgotten to take it out. The other Indians now ran back towards the

river, yelling loudly. By this time most of the men had gotten clear

of the brush and charged with McClure across the open ground.

...Captain McClure's volunteer forces pursued the Indians to the

Blanco River, where the fighting became more general. More of the

fifty-odd Comanches were killed as they tried to cross the water with

their stolen goods. Andrew Sowell shot and killed on Indian as he

tried in vain to climb a steep bank on the far side. In the end, they

left much of their spoils behind and moved swiftly from the area.

The whites chose not to cross the river and continue their pursuit.

They were fortunate to have not had any man killed or any serious

injuries sustained.

|