Topics (click on a topic to jump to that section)

When the Indians made their appearance at the home of James Landman

on the 26th day of November, 1860, it was the beginning of one of the

most far reaching raids ever made on the West Texas frontier. Furthermore,

no foray ever perpetrated by the Indians on the pioneers of the West,

excels the massacres to be related to exemplify the treachery and brutality

of the wild hordes of the plains.

Because of this gigantic raid, the exasperated citizens, rangers

and soldiers determined to carry the war to the Indians' own doors,

and to see the Indians paid dearly for this and the following dastardly

deeds. When this policy of retaliation was pursued, the Indians were

not only crushed, but Cynthia Ann Parker recaptured, after being in

the hands of the savages for more than twenty-four years.

Volumes have been written about the capture of Cynthia Ann Parker,

but few times, if ever, has a complete story of her recapture ever

been told. Much has been written about the fight in which she was

recovered, but little has been said about this particular raid, which

was the direct cause of the capture of Cynthia Ann Parker. And of

the two phases of this very important frontier history, the part that

has been heretofore left untold, from the standpoint of history, is

equal or superior to the capture of Cynthia Ann Parker herself.

James Landman and family lived about four and three-quarters miles

northeast of Jacksboro, and about three-quarters of mile east of the

home of Calvin Gage, who lived on Lost Creek. It was the 26th day

of November, 1860. James Landman and his fourteen year old stepson

named Will, were about one and a quarter miles to the east cutting

timber. Mrs. Landman, Jane Masterson, a young lady, Katherine Masterson,

also a young lady about fifteen or sixteen years of age, Lewis Landman,

a son, six or seven years old; and John Landman, a baby were at the

house.

A large band of Indians came from the north down Hall's Creek, and

charged the home of James Landman. Mrs. Landman and her seven-year-old

son Lewis, were brutally murdered by the barbarians, and the baby,

John, left unharmed. Jane and Katherine, for they placed her on a

horse. But poor Jane was roped and dragged the entire distance. Before

they left, the warriors cut open the feather beds, took the ticking

and emptied the feathers on the floor and ground. They also took other

things that suited their fancy.

After leaving the Landman home a horrible scene, the blood-thirsty

warriors, with Katherine on a horse, and Jane dragging on the ground,

started to the home of Calvin Gage, to further murder, pilfer and

plunder.

Mrs. Landman and her son Lewis were buried at Jacksboro.

When the Indians reached the home of Calvin Gage, the following people

were present: Mrs. Calvin Gage, Mrs. Katy Sanders, a mother-in-law,

Matilda Gage, age fourteen; Johnathan Gage, age five; Polly Gage, age

one and a half, and Mary Ann Fowler, age about ten years.

Joseph Fowler, about sixteen, brother of Mary Ann Fowler, and son

of Mrs. Gage by a former husband, had penned one ox and was down in

the pasture, at the time, almost a mile from home, in search of another.

When the Indians arrived at the frontier home of Calvin Gage, who

was away, they shot and killed Jane Masterson, dragged from her home

in the manner mentioned in the preceding section. The Indians brutally

slaughtered Mrs. Katy Sanders. They also shot Mrs. Calvin Gage, several

times with arrows, knocked her in the head and left her for dead.

Polly was also seriously wounded and left to die a lingering death.

But she and her mother recovered. The death of Mrs. Gage, however,

several years later was largely attributed to this horrible onslaught

of the savages. The Indians also shot Mary Ann Fowler and Johnathan

Gage. And to appease their peculiar sense of humor tossed one of the

babies of Mrs. Gage high up in the air only to see it fall flat on

the ground. To intensify the excruciating pain of this innocent little

infant, it was again several times tossed backward over an Indian's

shoulder.

Then at the home of Calvin Gage, the Indians murdered Mrs. Katy Sanders,

mother of Mrs. Gage, and left the latter dead; they also left Jonathan

Gage, Polly Gage, and Mary Ann Fowler badly wounded. No doubt, the

Indians thought each would die. They killed Jane Masterson as has

already been related. These brutal barbarians then ripped open seven

feather beds and emptied the feathers on the ground; and after pilfering

and plundering to their hearts content, rode away and took with them

Katherine Landman, Matilda Gage, and little Hiram Fowler. Matilda

and Katherine, both about fourteen years of age were savagely abused,

stripped of most of their clothes and then released.

By this time the girls could hear Joseph Fowler driving the belled

oxen, which had strolled away. Consequently, instead of returning

home, in their pitiable condition, they hurried to convey the news

to Joseph Fowler, for fear he would run into and be massacred by the

Indians. The three cautiously hurried to the house, and Joseph Fowler

personally told the author that it was impossible to conceive of the

terrible scene he saw on that occasion. A cold wind was coming from

the north and feathers were so badly scattered, they resembled snow.

Joseph and the two girls carried Mrs. Gage and Mary Ann into the house,

but Jonathan and Polly were able to walk.

As soon as possible, Dr. S.A. Cole and Dr. Milton Hays were called

to the aid of the injured, all of whom in due time recovered. But

the death of Mrs. Gage several years later, was attributed to her

old wounds. About one year after this tragedy the bones of little

Hiram were found several miles away, where he had either been murdered

by the savages or turned loose to starve. So up to this time the Indians

had killed five people, left four for dead, and carried Katherine

Landman and Matilda Gage several hundred yards from home.

A little later during the same day after the Indians charged the

home of these two frontier families, news was narrated in all directions,

and a posse of men was soon on the Indian's trail. Joseph Fowler left

the bedside of his dead and wounded, to convey the sad news to James

Landman and his stepson were just ready to start for home, and can

we really imagine the shocking effect of this sad news? And again

can we realize the paralyzing effect of the horrible scene which presented

itself to Mr. Landman at the time he reached his frontier home? Joe

Fowler then crossed the creek to the home of Wiley Gunter, John Fowler,

etc., to relate to them his sad story. When he returned home, it was

already dark. Numbers of people at that time had gathered in. Needless

to say, every able bodied person was ready to shoulder arms against

the savages. For such a sight they had never before seen.

Note: Before writing this and the preceeding section the author personally

interviewed Joseph Fowler himself, a stepson of Calvin Gage, and the

same Joseph Fowler who was driving the belled oxen, when this tragedy

lccurred.

Also interviewed A.M. Lasater, whose father-in-law was murdered

by these same Indians the following day, B.L. Ham, James Wood, and

others who were then living in that section.

Mary Tarkington Brown Crawford (circa 1832-1916), widow of John Brown,

who, in November 1860, was killed, scalped, and mutilated by the Comanches

near his home located sixteen miles northwest of Weatherford and about

four miles southeast of Whitt. Mary Brown was struck in the forehead

by a Comanche warrior's arrow, leaving a pronounced "widow's peak"

along her hairline. Mrs. Brown later married Simpson Crawford, noted

frontier rancher of Palo Pinto County.

(From the book, Savage Frontier, by Stephen L. Moore)

At the time of this particular raid, there were less than two hundred

families living in Jack County. Since it was reasonably certain the

savages would extend their foray further on into the settlements, the

local citizens hastily dispatched a messenger to Weatherford, for aid

and to alarm the people. At that time John Brown was living sixteen

miles northwest of Weatherford, near Rock Creek, and on the Weatherford-Jacksboro

Road. The messenger reached his home just before day, November 27, 1860.

From Mr. Brown, this "Paul Revere" of the Western Frontier

secured a fresh horse and hurried to Weatherford. Mr. Brown had about

thirty-five head of horses penned in the peach orchard near the house.

About sunrise he saddled one of his slowest ponies, and started to the

home of Mr. Thompson, his neighbor, who lived about two miles to the

West. Since the Indians had not been previously depredating in that

section he told his wife before he rode away, that the redskins would

not come that far south on this particular raid, but would eventually

do so. He then started unarmed on a slow pony to the Tompson home.

About thirty minutes after Mr. Brown had gone, and before reached

the home of Mr. Thompson, two of his slaves, a Negro woman, and a

boy about fourteen years of age, were on the outside of this yard

a short distance to the southwest of the John Brown home. This house

was newly constructed and was one and a half story "Log Cabin

mansion."

To their sudden amazement, when they looked up the road towards Jacksboro,

and saw about fifty or sixty Indians riding rapidly towards the house,

the Negro Woman told the boy they must hide or else be killed. This

brave Negro lad said, "No. I'll die with de misses and chilluns."

The Negro woman then ran and hid in the high grass in the peach orchard,

but the boy hurried to the house and related to Mrs. Brown, the Indians

were coming. The approaching warriors could now be plainly seen. Mrs.

Brown hurriedly gathered the following children: Mary, about ten years

of age, John, about eight, Teranna, about five, and Seaph, about two

months old, and took them upstairs. She then closed the trap door.

About this moment it was discovered that Annie, about two and one

half years of age, was missing, So the brave Negro boy named Anthony

Brown, after the Indians had completely surrounded the house, rushed

down stairs in search of Annie. She was found playing in the Negro

cabin, about thirty feet from the house. Annie at the time was dipping

ashes with a spoon. The Negro boy and the colored boy carried little

Annie upstairs. About this time Mrs. Brown heard the rattling of chains,

and since her husbands bridle reins had chains next to the bits, she

thought it was he coming. So she looked out of a window and said,

"Have you come." About that moment she discovered a savage

in the very act of shooting her. So she jerked back only in time to

receive an arrow in her ear. This weapon struck the window facing,

where she had been standing.

During this exciting time, the Indians were also chasing the horses

in the orchard and the Negro woman then hiding in the tall grass later

stated that if she had not been hidden under the tree, the Indians

would have ridden over her several times.

The blood thirsty savages cut the bell from one of the horses, and

started the herd westward toward the home of Mr. Thompson. They had

gone only about one-half mile, when the warriors met Mr. Brown unarmed.

He was soon killed with a lance, and scalped. But it is generally

supposed he wounded one of the warriors with a pocket knife, for evidences

of a wounded Indian were later discovered.

The Indians continued their course westward, crossed the line from

Parker into Palo Pinto County, and next appeared to exact their toll

of human lives, at the home of Ezra Sherman, who lived on Stagg's

Prairie, then known as Betty Prairie, and located a few miles north

and east of the present city of Mineral Wells.

Note: Before writing this article, the author personally interviewed

A.M. Lasater, who on June 8th, 1876, married Annie Brown, the little

daughter playing in the ashes with a spoon when rescued by Anthony,

the Negro boy. Mr. Lasater not only heard his mother-in-law many times

relate this story, but remembers the occurrence himself, for he was

a boy several years of age when this occurred.

Also interviewed Mrs. Wm. Metcalf, Mrs. H.G. Taylor, Mrs. Huse Bevers,

James Wood, E.K. Taylor, Joseph Fowler, Mrs. M.J. Hart, B.L. Ham,

James Eubanks, Mrs. Wm. Porter, and others who were living in Palo

Pinto and Parker County at the time.

In his book, Indian Depredations in Texas, J.W. Wilbarger provides an account of the murder of Mrs. Sherman, which appears below:

Ezra Sherman

The following story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

Mrs. Sherman's maiden name was Martha Johnson, a sister of Jerry Johnson,

an early settler of Parker County. She had been previously married and

later wedded to Ezra Sherman. They moved to Staggs Prairie in Palo Pinto

County, and lived there only a short time before this raid. Mr. and

Mrs. Sherman made their home in a small log cabin.

On November 27, 1860, Mr. and Mrs. Sherman and children were eating

dinner, when the same Indians mentioned in the preceding sections,

surrounded their home. Some of the warriors stepped in the door and

told the family to "Vamoose." Ezra Sherman then took his

wife and children and started east toward their nearest neighbor,

who lived on Rock Creek in Parker County. Mr. Sherman, like Mr. Brown

was unprepared to fight and had no guns at home.

When this pioneer family reached a point about one hundred and fifty

or two hundred yards east of their residence, about six of the warriors

suddenly dashed up, took Mrs. Sherman by the hair of the head and

started back toward the house. Mr. Sherman was again advised by the

Indians to "Vamoose." The oldest child, a son of Mrs. Sherman

by her former husband, hid in a brush pile where he could see all

that transpired. Mr. Sherman with the two smaller children went on

to the home of a neighbor.

The wife and mother was then carried back toward the house, being

robbed by the remaining Indians. When the blood-thirsty barbarians

dragged Mrs. Sherman, to a point, about two hundred yards from the

house, she was tortured in an inconceivable manner. This faithful

frontier mother was outraged, stabbed, scalped, and left for dead.

An Indian on a horse held up her hands while another pushed an arrow

under her shoulder blade. Neil S. Betty later placed this arrow in

a museum, perhaps in Dallas, as a symbol of the severe suffering administered

to Mrs. Sherman, by the blood-thirsty savages.

The house was completely robbed and pilfered by the Comanches. The

warriors took cups and saucers and drank molasses out of a large barrel,

which Mr. and Mrs. Sherman had stored away for the winter. The blood-thirsty

warriors also ripped open feather and straw beds, took the ticking

and emptied the contents on the floor and ground. They took Mrs. Sherman's

family Bible, for what purpose no one knows, unless as a token of

war. The savages then took a southwest course almost in the direction

of the present city of Mineral Wells.

Mr. Sherman secured a gun from a neighbor and returned. His wife

was found still alive and in a pitiable condition. His house after

being robbed and ruined by the raging savages, was fired; but since

it was a rainy day, the building refused to burn.

The splendid frontier citizens, the trail blazers of the great west,

administered to Mrs. Sherman all possible aid. For three days she

lived and continually talked about her horrible experience.

Many times she shamefully referred to that "Big old red-headed

Indian." No full blooded Indian was ever known to be red-headed.

Was this red-headed man the same individual who made his appearance

in other raids before and after this time? Was it some one the Indians

had captured when a child and reared to be a blood-thirsty savage?

Or was it some renegade ruffian of our own race? Nevertheless, again

we find the presence of a red-headed man with the red men.

Mrs. Sherman was buried to the west of the Fox family in the Willow

Springs Graveyard, several miles east of Weatherford.

Note: Before writing this section, the author personally interviewed

a daughter of R.C. Betty, Mrs. William Porter, who stayed with Mrs.

Sherman a great portion of the three days she lived, after being brutally

assaulted by the savages. Also corresponded with Mrs. Joe Sherman

a daughter-in-law of Mrs. Ezra Sherman, and interviewed those mentioned

in the preceding and succeeding sections relating to this particular

raid.

I have misplaced another account of Mrs. Sherman's ordeal that described

the Indians braiding her hair with a horse's tail then running the horse

through rocks and cactus. John Graves' moving account of her ordeal

follows.

They rode up to the cabin while the Shermans were at dinner on November

27, 1860-dinner in rural Texas then and up into my young years being

the noontime meal. There were half a hundred of them, painted, devil-ugly

in look and mood. It was the year after the humiliating march up

across the Red under good, dead Neighbors; the frontier country

was not yet strange to The People, nor were they yet convinced they

had lost it. They wanted rent-pay for it in horses, and trophies,

and blood, and boasting-fuel for around the prairie campfires in

the years to come. Horses they had taken in plenty-300 or so of

them by the time they reached the Shermans'-and they had just lanced

John Brown to death among his ponies to the east, and the day before

had raped and slaughtered and played catch-ball with babies' bodies

at the Landmans' and the Gages' to the north.

Though the Shermans did not know about any of that,

their visitors lacked the aspect that a man would want to see in

his luncheon guests-even a sharper frontiersman than Ezra Sherman,

who, in that particular time and place, with a wife and four kids

for a responsibility, had failed to furnish himself with firearms.

The oldest boy, Mrs. Sherman's by an earlier husband

who had died, said: "Papa…"

But by the time Ezra Sherman turned around, they were

inside the one-room cabin, a half-dozen of them, filling it with

hard tarnished-copper bodies and the flash of flat eyes and a smell

of wood smoke and horse sweat and leather and wild armpits and crotches.

Behind them, through the door, were the urgent jostle

and gabble and snickering of the rest.

"God's Heaven!" Sherman said, gripping the

table's edge. Martha Sherman said: "Don't show nothin'. Don't

scare."

She had come to the frontier young with a brother

and his family, but even if she'd only come the year before she'd

have known more about it than her husband. There was sense in her,

and force. Her youngest started bawling at the Indians; she took

his arm and squeezed it hard until he shushed, looking up the while

into the broad face, slash-painted diagonally in scarlet and black,

of the big one who moved grinning toward the table. He wore two

feathers slanting up from where a braid fanned into the hair of

his head, and held a short lance.

"Hey," he said. "Hey," Ezra Sherman

answered. The Indian said something. "No got whisky,"

Ezra Sherman said. "No got horse. Want 'lasses? Good 'lasses."

"You're fixin' to have us kilt," his wife

said, and stood up. "Git!" she told the big Indian.

He grinned still, and gabbled at her. She shook her

head and pointed to the door, and behind her heard the youngest

begin again to cry. The Indian's gabbed changed timbre; it was Spanish

now, she knew, but she didn't understand that either.

"Git out!" she repeated.

"Hambre," he said, rubbing his bare belly

and pointing to the bacon and greens and cornbread and buttermilk

on the table.

"No, you ain't," she said, and snatched

up a willow broom that was leaned against the wall. But his eye

caught motion to the left and she spun, swinging the broom up and

down and whack against the ear of the lean, tall, bowlegged one

who had hold of her bolt of calico. She swung again and again, driving

him back with his hands raised, and then one of the hands was at

a knife in his belt, and Two-feathers's lance came down like a fence

between them. Her broom hit it and bounced up. The three of them

stood there… Two-feathers was laughing. The lean Indian wasn't.

The calico lay on the floor, trampled; she bent and picked it up,

and her nervous fingers plucked away its wrinkles and rolled it

again into a bolt.

"Martha, you're gonna rile 'em," her husband

said.

"Be quiet," she told him without looking

away from Two-feathers's laughing eyes.

"Good," the big Indian's mouth said in English

from out of the black-and-red smear. With his hand he touched the

long chestnut hair at her ear; she tossed her head away from the

touch, and he laughed again. "Mucha Mujer," he said.

The lean one jabbered at him spittingly.

Martha Sherman's oldest said calmly: "That's

red hair."

It was. In the cabin's windowless gloom she had not

noticed, but now she saw that the lean one's dirty braids glinted

auburn, and that his eyes, flickering from her to the authoritative

big one, were green like her own. Finally he nodded sulkily to something

that Two-feathers said. Two-feathers waved the other warriors back

and turned to where Ezra Sherman stood beside the dinner table.

"No hurt," he said, and jerked his head

toward the door. "Vamoose" "Yes," Ezra Sherman

said, and stuck out his hand. "Friend. Good fellow."

The big Indian glanced ironically at the hand and

touched it with his own. "Vamoose, " he repeated.

Ezra Sherman said: "You see?" He don't mean

no trouble. I bet if I dip up some molasses they'll just…"

"He means go," Martha Sherman said levelly.

"You bring Alfie."

"Go where?"

"Come on!" she said, and the force of her

utterance bent him down and put his callus-crusted farmer's hands

beneath the baby's arms and straightened him and pulled him along

behind her as she walked, holding the hands of the middle children,

out the door into the stir and murmur of the big war party. It was

misting lightly, grayly… The solemn oldest boy came last, and

as he left the cabin he was still looking back at the green-eyed,

lean, redheaded Comanche.

Two-feathers shouted from the door and the gabble

died, and staring straight ahead Martha Sherman led her family across

the bare wet dirt of the yard and through the gate, past ponies'

tossing hackamored heads and the bristle of bows and muskets and

lances and the flat dark eyes of fifty Comanches. She took the road

toward the creek. In a minute they were in brush, out of sight of

the house, and they heard the voices begin loud again behind them.

Martha Sherman began to trot, dragging the children.

"Where we goin' to?" Ezra Sherman said.

"Pottses'."

He said: "I don't see how you could git so ugly

about a little old hank of cloth and then leave the whole house

with-"

"Don't talk, Ezra," she said. "Move.

Please, please move." But then there was the thudding rattle

of unshod hooves on the road behind them, and a hard-clutching hand

in her chestnut hair, and a ring of ponies dancing around them,

with brown riders whose bodies gave and flexed with the dancing

like joined excrescences of the ponies' spines.

Before she managed to twist her head and see him,

she knew it was the redheaded one who had her; he gabbled contemptuously

at Ezra Sherman, and with the musket in this other hand pointed

down toward the creek. The pony shied at the motion, yanking her

off balance. She did not fight now, knowing it pointless or worse.

"Durn you, let her be!" Ezra Sherman yelled,

moving, but a sharp lancepoint pricked his chest two inches from

the baby's nose and he stopped, looking up.

"Go on, Ezra," his wife said. "They'll

let you go."

Ain't right," he said. The lancepoint jabbed;

he backed away a half-foot. "Go on."

He went, trailing stumbling children, and the last

she saw of them was the back-turned face of her oldest, but one

of the horsemen made a plunging run at him, and he turned and followed

the family… The redhead's pony spun and started dancing back

up the road. The hand jerked her hair, and she went half down, and

a hoof caught her ankle; then she was running to keep from dragging.

Snow was drifting horizontally against the chinaberries she had

planted around her dooryard, though it was not cold; she saw finally

that it was feathers from her bed, which one of them had ripped

open and was shaking in the doorway while others laughed. In a shed

some of them had found the molasses barrel and had axed its top

and were drinking from tin cups and from their hands, throwing the

ropy liquid over each other with yells. The old milk cow came loping

and bawling grotesquely from behind the house, A Comanche astride

her neck, three arrows through her flopping bag…

Deftly, without loosening his grip, the redhead swung

his leg across his pony's neck and slid to the ground and in one

long strong motion, like laying out a rope or a blanket, threw her

flat. Two of the others took her legs, pulling them apart. She kicked.

The flame-pain of a lance knifed into her ribs and through her chest

and out the back and into the ground and was withdrawn; she felt

each inch of its thrust and retreat, and in a contraction of shock

there relaxed elsewhere, and her legs were clamped out wide, and

the lean redhead had let go of her hair and stood above her, working

at his waistband.

Spread-eagled, she twisted her head and saw Two-feathers

a few yards away, her big Bible in his hands, watching. Her eyes

spoke, and maybe her mouth; he shrugged and turned toward the shed

where the molasses barrel stood, past a group that was trying to

light fire against the web cabin wall…

The world was a wild yell, and the redhead went first,

and the third one, grunting, had molasses smeared over his chest

and bed feathers stuck in it, and after that she didn't count; though

trying hard she could not slip over into the blackness that lay

just beyond an uncrossable line. Still conscious, and that part

over, she knew when one on horseback held her arms up and another

worked a steel-pointed arrow manually, slowly, into her body under

her shoulderblade, and left it there. Knew, too, when the knife

made its hot circumcision against the bone of her skull, and when

a horseman messed his fingers into her long hair again and she was

dragging beside his panicked, snorting pony. But the hair was good

and held, and finally a stocky warrior had to stand with a foot

on each of her shoulders as she lay in the plowed field before the

house, and peel off her scalp by main force. For a time after that

they galloped back and forth across her body, yelling-one thing

she recalled with a crystallinity that the rest of it lost, or never

had, was that no hoof touched her-and shot two or three more arrows

into her, and went away. She lived for four days (another writer

says three, and another still says one, adding the detail that she

gave birth to a dead child; take your pick), tended by neighbor

women, and if those days were anything but a continuing fierce dream

for her, no record of it has come down.

In delirium, she kept saying she wouldn't have minded

half so much if it hadn't been for that red hair…

The oldest boy had quit his stepfather and had circled

back through the brush and had watched it all from hiding. No record,

either, states how he felt about Comanches afterward, or the act

of love, or anything.

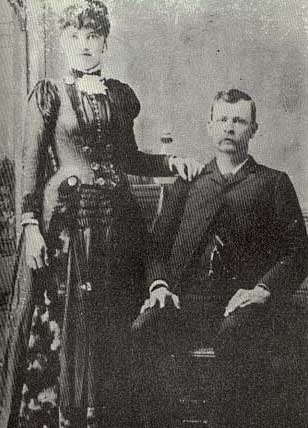

Younger brother, Joe Sherman with wife, Pearlina Underhill Sherman.

No picture or record exists of his older brother.

The above story is from the book, Goodbye to a River,

by John Graves.

After the Indians left the home of Ezra Sherman, they stopped about

two or three miles north of the present city of Mineral Wells. The savages

then took a northwest course toward Turkey Creek and next appeared at

the home of Joe Stephens. But here they did little damage, and soon

went away. Joe Stephens counted fifty-five savages painted for war.

The Indians now had a herd of about three hundred head of stolen

horses. They made their next stop about one mile from the home of

William Eubanks, who lived about five or six miles northwest of Mineral

Wells. Four or five of the warriors were sent to reconnoiter his home.

These Indians were first discovered by James G. Eubanks, about eleven

years of age, who in company with John and George Eubanks, had been

to the spring for water. James told his mother and older sisters that

his father was coming. The sister came out to see, but soon discovered

the horsemen were Indians. The three Eubanks girls, Mary, age eighteen,

Emily, fifteen, and Guss, thirteen, put on men's hats, and stood on

a bench stationed near the strongly fortified picket fence, and just

on the inside of the yard. Only their heads and shoulders could be

seen. Mary the oldest girl also armed herself with a loaded double

barrel shotgun. The Indians then dashed up as if they intended to

make a charge, but when Mary pointed the gun as if she intended to

shoot, the savages circled and rode away. Had these brave frontier

girls become frightened, perhaps a different story would have to be

related. Mary actually fired one shot and the gun kicked her from

the bench. It had the desired effect, however, for the Indians appeared

frightened, and hurriedly made their retreat.

The savages then started toward the mouth of Big Keechi, a favorite

Indian crossing. But it was not long before another unusual event

transpired.

During the dark hours of night, Wm. Eubanks, who was away when the

Indians visited his home, and who was now returning, found himself

surrounded by about three hundred head of horses, and fifty-five warriors.

Since it was dark, it occurred to him that the safest thing to do,

was to remove his hat, assume a stooping position like an Indian and

follow the herd. This he did, but made it a special point to drop

behind as rapidly as he could. Finally, when he reached the timber,

and had an opportunity to slip away, he lost no time in reaching his

residence on Turkey Creek.

It was a rainy, misty night, but a bright moon was shining beyond

the clouds. The savages crossed Big Keechi above its mouth and then

took a westerly and northwesterly course toward Dark Valley. When

the Indians crossed the rough country, bordering on the breaks of

the Brazos near the mouth of Keechi, they lost several of their stolen

horses. Each of the thirty-five head of Mr. Brown's horses returned

home, including the horse he was riding when killed.

During the following day, when the Indians passed the home of Jowell

McKee, who then lived in Dark Valley, near the Flat Rock Crossing,

about eight miles north of Palo Pinto and seven miles southwest of

Graford, they took about three hundred head of his horses. The Indian's

herd now consisted of approximately five or six hundred head, and

was about one half mile wide.

After leaving the home of Jowell McKee, the savages discovered Tom

Mullins and Billy Conatser. An exciting chase followed with the latter

in the lead. Mullins and Conatser, however, were not overtaken before

they reached Ansel Russell's store, which was about one and a half

miles west of Graford, and on the old Fort Worth and Belknap Road.

And this brings to a close one of the largest forays ever made by

the savages on the West Texas Frontier. Seven people were killed,

five wounded, two innocent girls made captives, but later released,

and several others seriously menaced and greatly frightened by their

presence.

Note: Before writing this section, the author personally interviewed

James G. Eubanks, who first saw the Indians when they appeared at

the home of William Eubanks; also interviewed Mrs. H.G. Taylor, Mrs.

Huse Bevers, A.M. Lasater, Mrs. M.J. Hart, Martin Lane, James Wood,

E.K. Taylor, B.L. Ham, Joe Fowler, John McKee, whose father lost

the two or three hundred head of horses in Dark Valley. Also interviewed

others mentioned in the preceding sections relating to the same raid.

This is, no doubt, by far the most detailed and accurate amount of

this major raid that has ever been offered. And it is the result of

hundreds of miles of hard driving, and many months of close study.

The above story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by

Joseph Carroll McConnell. |