Charley Goodnight (as pioneers all called him) often visited in the

Lasater home, when the writer was a child. His mother Mrs. Sheek and

grandmother Lasater were neighbors at old Black Springs during the Indian

times. After grandmother lost her eyesight she made her home with the

writer's parents for years. Goodnight and other old-timers were thoughtful

to drop in to see her. It was through these visits the writer heard

much about pioneer life, Indian raids, etc. After some of these visitors

departed, the writer imagined she saw Indians every time she stepped

out after dark.

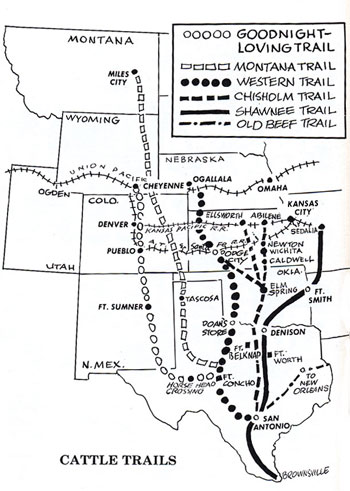

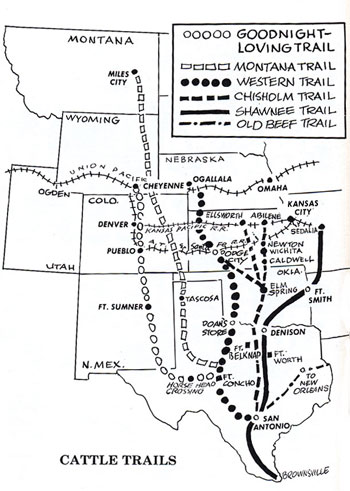

Map from the book, Panhandle Pilgrimage, by Pauline Durrett and R.L. Robertson

The writer remembers what Charley Goodnight said about his association

with Loving, and Grandmother Lasater often spoke of the details leading

to Loving's death. It was about 1858 when Loving headed a herd of

cattle for Chicago, on the first northward drive ever made from Texas.

In the Spring of 1859, he drove cattle to Colorado. It was after the

war that he formed a partnership with Charley Goodnight of Palo Pinto

County. In 1867, Loving lost his life on one of these drives to Colorado.

While the herd was in New Mexico, Loving and one-armed Wilson, (so-called

because Wilson had only one arm) started on ahead of the herd, first

promising Goodnight that they would travel by night on accounts of

the Indians. But, after about two nights of traveling and having seen

no signs of Indians, they decided it was safe to travel by daylight.

On the third day they were attacked by about eighty Indians. In the

battle Loving was wounded in the arm. They had managed to secrete

themselves in a cave-like hole. It was so small there was hardly elbow

room for the men to handle their rifles. The two men were hardly settled

in the cramped position when the Indians opened fire. These two men

held the Comanches at bay until about sunset, when an Indian slipped

through a nearby canebrake and succeeded in wounding Loving. Wilson

poured lead into the canebrake, then turned to relieve his companion.

"They got me," stammered Loving. "Get out if you can

and save yourself, find Goodnight and tell him what has happened."

"One-armed Wilson" refused to go. He worked as fast as he

could in cramped quarters, trying to bandage Loving's wound with a

portion of his shirt. Then lying on his armless side with his six-shooter

in his hand, awaited the next move. There was a rustle in the cane

but not from Indians, in the fading light Wilson beheld a huge diamond-backed

rattlesnake which crawled out of the cane and headed directly for

the hole, The men shuddered as they realized that the snake was determined

to share their place of refuge. In a moment it stopped, coiled up

with its head a few inches from Wilson's knees. The two men lay speechless,

afraid to move a muscle. It was a mere question of choice of two evils-the

poisonous fangs or arrows. Their cramped muscles were almost unbearable,

cold perspiration stood on their brows. In about half an hour, which

seemed a lifetime to the two occupants of the cave-like hole, the

snake quietly glided its scaly body across Wilson's feet, raised its

head for a moment, then left the hole by the same sweet route it had

entered. Again, Loving urged Wilson to try to escape. After much hesitation,

Wilson agreed to go in search of help. Loving insisted that Wilson

take his rifle, saying, "It is the best of the two. Find Goodnight,

If I am not here upon your return, well-just tell the folks about

it."

After loading every chamber of his cap and ball pistol, Wilson slipped

off his boots and pants and started crawling toward the river. When

he reached the river he soon learned that a one-armed man could not

make headway trying to swim and carry a rifle. He hid the guns and,

unarmed, cautiously paddled down the stream.

Throughout the long night, Loving lay listening; queer noises haunted

him. The approach of day revealed to the cattleman the reason for

those noises he had heard through the night. The Indians had been

digging a tunnel through the sand toward his place of refuge, and

about twenty feet away, he saw an Indian busily digging in. With one

shot Loving killed the Indian. Several times during the forenoon the

Indians tried to reach him via trench, but after he had killed two

more warriors, they drew to higher ground nearby and began throwing

huge rocks into the hole, missing their mark each time. He lay all

day without food or water. The river was nearby but he dared not venture

out. Night brought a heavy rain which lessened his thirst, but rendered

his guns useless. He felt sure the Indians would make another attack

at daylight, but after waiting until the sun was well up and no signs

of an attack, he crawled out of the hole and staggered toward the

river. He tried to reach a point on the river where he knew the trail

herd would cross, but became exhausted and sank down in a clump of

bushes on the bank of the river.

Footsore and hungry, Wilson reached the Goodnight herd on the fourth

day. Goodnight and six of the men went to Loving's relief. They found

the hole marked by arrow spikes, also found Wilson's rifle, but no

sign of Loving. They searched the surrounding country to no avail.

They returned to the herd and continued the trial with heavy hearts

and bowed heads.

Enroute they met a man who told them that Loving was not dead but

doing nicely at Fort Sumner, where he had been brought by three Mexicans

and a white boy who were passing on their way from Mexico when they

encountered Loving. He paid them $ 250.00 to carry him to Fort Sumner.

When Goodnight heard this report, he saddled a fresh mount and hastened

to Loving's bedside. He found him resting nicely, but in a few days

gangrene set up and an operation was necessary; then a second operation,

but in a few hours this brave, noble pioneer passed on. Before his

death he requested that he be sent back to Texas. There was difficulty

in securing a suitable casket and it was found necessary to bury him

temporarily in New Mexico, but as soon as Goodnight could freight

a metallic casket with a guard of six men, he began the slow, sad

march homeward over mountains and plains, where Oliver Loving had

driven one of the first herds ever driven from Texas. Among the guards

who accompanied the body back to Texas was the late W.D. Reynolds

of Fort Worth, Texas. After long, weary days and dreary nights the

body was delivered to the Jack County cattleman's family. Oliver Loving

rests today in the picturesque cemetery at Weatherford, Texas.

Loving was recognized a leader among men, possessing varied traits

of character which were of special value in those days of constant

danger. He was one among the seven men who volunteered to find Bill

Willis and his band (who, with a party of Indians, murdered the Mason

and Cambren families in 1858) and bring them back to Jack County.

More