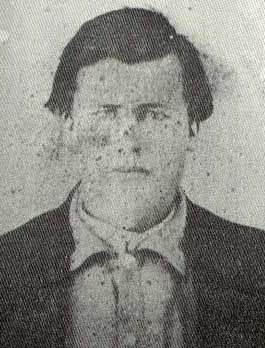

M.Y. (Roe) Littlefield Wounded |

|

Approximately three miles from Millsap, about noon, and just after

a shower, in 1868, Webb Gilbert turned out his horses to graze. At

the time, sixteen Indians were concealed on a red bluff not a great

distance away, and in a short time rounded up the horses. Indian signs

were soon discovered, however, and Johnce Gilbert and Amos Ashley,

discovered the horses were gone. Word was conveyed to neighbors, who

came over to the Littlefield Bend. In a short time, M.Y. (Roe) Littlefield,

Webb Gilbert, Johnce Gilbert, Geo. Emberlin, Carroll Mabry, Tom Lane,

James Littlefield, Amos Ashley, and, perhaps, one or two others were

soon in hot pursuit of the savages. When the Indians were crowded,

they began to throw off blankets and other loose luggage that could

be spared. The Indians were pursued until overtaken about three or

four miles further. Here a running fight followed. In a short time

the Indians made a stand, fired a few shots, dropped their stolen

horses, and then made a retreat toward the mountains, and occasionally

continued to drop blankets and other baggage. When the Indians were

about three miles north of Millsap, they were again closely crowded

and a running fight followed with the Indians still in the lead. One

by one the fleeing Indians were shot from their horses, and finally

M.Y. (Roe) Littlefield received a serious wound.

M.Y. (Roe) Littlefield

When the fight was over, the citizens took the back trail to scalp

the fallen Indians. Only about two scalps, however, were recovered.

One or two other Indians who had been wounded, were gone. M.Y. (Roe)

Littlefield recovered, but approximately eighteen years later his

death was largely attributed to his old wound received in this fight.

Roe Littlefield was a member of the well-known Littlefield family,

who located in Littlefield Bend December 24, 1854.

Note: Author personally interviewed Dave and F.S. Littlefield, James

and Sam Newberry, R. Bradford, Henry Blue, and others who lived in

Palo Pinto and Parker Counties at the time.

The above story is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by

Joseph Carroll McConnell.

In the running fight mentioned by McConnell, the following story is

from the book, A Cry Unheard, by Doyle Marshall:

Twenty-five-year-old Monroe Littlefield rode in advance of the other

settlers, firing at the band. After the raiders had passed the Millsaps

double log cabin and were east of the home of a widow living about

one-quarter mile north of the Millsaps place, the fleeing band began

to split an age-old maneuver commonly employed by the Indians to confuse

their pursuers. As one of the Indians turned his horse off the trail

to the right and up a steep hill, Roe Littlefield followed. When he

saw another Indian aim a six-shooter at him and, at the same time,

found that his own pistol was empty, Littlefield quickly reversed

his direction, reduced the target by lowering himself close to his

horse's body, and spurred his steed in an attempt to escape the field

of battle. However, a well-aimed shot from the Indian's gun struck

Littlefield in the back at the point of the shoulder blade. This ended

the fight at a location just northeast of the widow's cabin. Seriously

injured, Littlefield was carefully moved to the nearby Millsaps home,

where Fayette Ikard attempted to relieve the pain by applying wet

cloths to the wound until the Weatherford doctor removed the ball

from must above the collarbone. The doctor "sterilized"

the wound by pushing a pure silk handkerchief through it. In spite

of the seriousness of the injury, the crude operating procedures,

and the absence of sanitary precautions against infection, Littlefield

survived. The hospitable Millsaps family cared for Littlefield in

their home for about six weeks, when the patient partially recovered

enough to make the trip home to Littlefield Bend. Littlefield's neighbors

did his farm chores during his extended convalescence.

...Some of the boys of the settlement found the two scalped Indian

bodies, tied them to their horses' tails, and dragged them to Millsaps'

home for viewing. One of the boys, Sam Newberry, from the Newberry

Community, east of the Millsaps place, told that the Indians were

so tough that dragging them over rocks and brush did nothing to their

skin. It soon became necessary to dispose of the bodies. In order

to avoid any appearance of honoring the enemy with a burial-the remains

were removed to the widow's home north of the Millsaps place and were

thrown to her ravenous hogs.

Because the North Texas settlers had seen the scalped and mutilated

bodies of their friends and family members, viewing the scalps or

bodies of the savage victims seemed to satisfy the settlers' curiosity

and craving for vengeance. In addition to the public showing of the

bodies at the Millsaps home, there were at least two other instances

of such local public displays. In much the same sense that glory was

conferred upon a savage by his people by means of a scalp dance, when

he proudly displayed the scalp of a white settlers, the frontiersman

who could prove his valor by taking an Indian's scalp, or if possible,

the victim's body, achieved instant fame and honor from settlers all

along the Texas frontier.

During the heat of the Indian forays in and around Parker County

a party of frontier volunteers originating in Palo Pinto County scouted

the countryside in search of depredating bands which continued to

ravage the farms and ranches of the outlying settlers. Because they

were seldom successful in trailing the marauders, the volunteers,

on one occasion, were elated at their unusual success in dispatching

one of the enemy. The victim's body was brought to an abandoned house

near the village of Palo Pinto, where it was viewed by the impassioned

settlers throughout the area. Also proudly displayed by the victors

were the victim's scalp, bow, arrows, and feather headdress taken

in the battle.

On a spring day in 1863, the alarm was given in the north Parker

County communities of Erwin and Goshen that Indians were in the area.

Several families gathered at the home of "Uncle' Steve Erwin.

The men gathered their horses, turned them into a green wheat field,

and selected a detail to guard them through the night. While the women

and children spent the night in the house, the guards stood watch

over the horses. As it began to rain some time after midnight, two

of the guards, Steve Erwin and Henry Roberts, went to the house for

protective clothing. Sam Stennett and Jack Fidler remained on guard

in the fence corner. When Erwin and Roberts left, two Indians, unaware

that the two guards remained on duty, quietly laid down the rail fence

and began to round up the horses. Limited with only single-shot cap-and-ball

weapons, the remaining two guards killed one of the Indians; the surviving

Indian disappeared into the adjacent woods. The guards tied one end

of a rope to the saddle horn and the other end around the victim's

neck-then dragged the body to the house. On the following morning

settlers came from miles around to view the spectacle while the scalp

was still in place. "Uncle" Steve Erwin was selected to

"lift" the scalp, and he proved capable of performing the

task. After the excitement diminished, a log-chain was hitched around

the Indian's neck, and the body was dragged by a team of oxen and

rolled into a ravine about a mile away. Later, some of the youngsters

of the settlement went to the ravine, took strips of skin from the

victim's back, and used them for shoelaces. Sometime later, after

the body decomposed, the Indian's arm and leg bones were used for

making gun stocks and file handles. One unusually imaginative settler

put a bail on the inverted skull and used it as a bucket for carrying

fish bait.

|