Posted

on Sun, Sep. 15, 2002

Miss Charles speaks

FIRST OF TWO EXCERPTS FROM "OUR LAND BEFORE WE DIE"

Jeff Guinn

Star-Telegram Staff Writer

One

day in summer 1994, Star-Telegram Books Editor Jeff Guinn headed to

Brackettville, Texas, to write a newspaper story on the little-known

past of the Seminole Negro, whose descendants still live in the dusty

little town. This journey inspired his book, Our Land Before We Die:

The Proud Story of the Seminole Negro , published this week and nominated

for both the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award by publisher Tarcher/Putnam.

It is the first oral history of the Seminole Negro ever written. Guinn's

book tells us of a people who sought shelter in the shadow of a tribe

whose land and welfare already hung in the balance. And yet in their

tireless journey -- from Florida to Indian Territory in Oklahoma,

on the 700-mile flight from persecution that took them across the

Rio Grande into Mexico, and then back across the Rio Grande to Texas

-- they never surrendered hope of attaining land of their own. But

that hope was continually thwarted; in 1914, after decades of dedicated,

distinguished performance as scouts in battles against the Comanche,

Apache and border outlaws, the Seminole Negro were marched at gunpoint

off the grounds of Fort Clark in Brackettville. The government had

no more use for them, or for the agreement the tribe believed had

guaranteed them land of their own in return for their service. Still,

modern-day descendants celebrate Seminole Heritage Days each year

on the third Saturday in September -- and still hope for land of their

own.

Today,

and in Monday's Life & Arts section, we print excerpts from the

prologue and Chapter One.

Miss

Charles Speaks

PROLOGUE

Miss

Charles Emily Wilson, last survivor of the Seminole Negro camp on

Fort Clark across from Brackettville in South Texas, doesn't organize

the Seminole Heritage Days celebration anymore. She has what her Brackettville

friends call "the Alzheimer's," and has been moved 70 miles

away to a niece's home in Kerrville.

It

was 18 years ago that the 91-year-old retired schoolteacher, known

to everyone as "Miss Charles," declared there had to be

an annual Brackettville event celebrating the rich history of the

Seminole Negro. With the tribe's modern-day young people getting so

distracted by television and video games, Miss Charles warned, the

storytelling tradition of the Seminole Negro was fast disappearing.

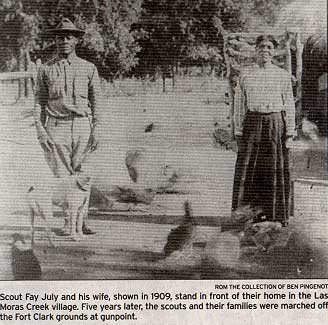

Tribal

descendants had scattered around the Southwest after the terrible

day in 1914 when the United States Army, having run out of uses for

scouts on horseback, evicted them from the shady Las Moras Creek village

on Fort Clark land where they'd lived for more than 40 years. Miss

Charles herself was the last one left who'd been there when the empty

wagons arrived, who saw the soldiers with their guns and heard the

old people crying when they were left on the Brackettville streets

to survive or starve -- the Army didn't care anymore.

The

story of the Seminole Negro was so glorious, going back to the days

when the Spanish owned Florida and escaped slaves eagerly ran south.

There was so much everyone, not just the Seminole Negro children,

should know about the great chiefs, the great battles -- how the Seminole

Negro fought the U.S. Army in Florida, then helped the Mexicans guard

their borders, then returned to Texas to show the Americans how to

finally beat down the Apache. Whole history books could have, should

have, been filled with these things.

But

historians overlooked the Seminole Negro. Only tribal bards told the

stories, and there were fewer of them as years passed and people died

or drifted away. Now, Miss Charles said she was getting on, her memory

might weaken at any time, and after she was gone, knowledge of all

those great and terrible times still had to be passed down from one

generation to the next, or else everything that had happened to the

Seminole Negro would be forgotten, and the blood and tears shed over

centuries would come to nothing.

So

they chose the third Saturday in September, when the blast-furnace

South Texas heat abates a little. Miss Charles and other tribal elders

conferred with Brackettville leaders. Traditionally, whites among

the 1,700 or so town residents never cared much for their dark-skinned

neighbors, whose numbers had steadily dwindled over the years, though

many Brackettville Hispanics, comprising about half the population,

had some Seminole Negro blood in them. But times had changed enough

so everyone agreed it would be good for the community as a whole to

have a Seminole Negro celebration.

Miss

Charles orchestrated everything -- a parade, the wearing of traditional

turbans and cloaks, gospel singing, dancing in the cool of the evening

and, above all, time for the children to hear the tales of Abraham

and John Horse, of the slaves who ran away to Florida and the Seminole

tribe that welcomed them; about fighting the American Army to a bloody

draw in the early 1800s, then relocating to Indian Territory; the

treachery that awaited the Seminole Negro there and the amazing exodus

to Mexico that, 150 years later, still seems almost impossible to

comprehend, it was so awful and yet so brave; then the fine service

to the Mexican government and the request from the Americans to come

back to Texas. Help us defeat the Apache and we'll give you land of

your own, that was the promise, and, though the promise was broken

by the white men, the tribe's children needed to know, to be proud,

that their ancestors, the Black Indian scouts, more than kept their

part of the bargain.

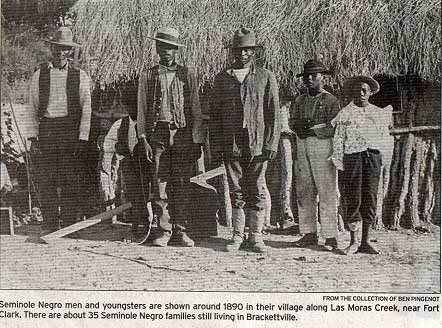

For

13 years, Seminole Days went almost according to plan. The 35 or so

Seminole Negro families left in town were joined by a few hundred

scout descendants who came back to visit from Oklahoma or Mexico or

wherever they had drifted, some from as far away as California and

Illinois. They didn't come for the scenery -- Brackettville is a charmless

hamlet between Uvalde and Del Rio that ceased to have a reason to

exist when Fort Clark was shut down in 1946. The surrounding countryside

is flinty and desolate.

When

John Wayne wanted to film The Alamo someplace so isolated that nobody

would bother his cast and crew, where he could blow up buildings and

not have to worry about scarring the countryside, he chose a ranch

just outside town. Filming ran three weeks over schedule in part because

hundreds of rattlesnakes had to be cleared off the set every morning.

Brackettville is a place most people don't go on purpose, except for

the oasislike grounds of adjacent Fort Clark, and rights to any of

that land were unceremoniously taken from the Seminole Negro in 1914.

No,

scout descendants came because they loved Miss Charles -- she had

taught most of them, or their parents, or their cousins, in elementary

school -- and because the Seminole Negro value family ties with a

devotion almost unimaginable to outsiders who haven't shared their

generations of incredible struggle. If the crowd never seemed to include

as many young people as Miss Charles had hoped, well, perhaps they

would be more interested next year. Saturday's events went on from

morning until dark, and on Sunday there were outdoor services in the

tiny tribal cemetery outside town, the only property the Seminole

Negro have been able to retain. Four Medal of Honor winners are buried

in that cemetery, but their descendants must ask permission before

visiting the Fort Clark site where Adam Payne, John Ward, Isaac Payne

and Pompey Factor once lived.

So

for years the annual get-together was a success. Occasionally, people

would talk about how Miss Charles was looking frail, probably it was

time for somebody else to really jump in and take over, but it is

human nature to take people like her for granted. Then Miss Charles

turned 90, and suddenly she couldn't remember anyone's name. Now she's

brought down from Kerrville as guest of honor, but it isn't the same.

Nobody

can tell the old stories like Miss Charles, except maybe Willie Warrior,

and he's in his 70s, has heart disease and doesn't get along well

with the younger officers of the Seminole Indian Scouts Cemetery Association,

the group organized by Miss Charles to tend the cemetery and serve

as de facto keepers of the tribal flame. So the speakers now are less

interesting -- they lack rhythm, and they take an hour to say what

Miss Charles or Willie Warrior could have told better in 10 minutes.

The heat seems more oppressive, too, and the teen-agers still don't

come. A cynic might even point out that more people ride in the parade

than line up to watch it; Brackettville's nontribal citizenry apparently

has better things to do with its third Saturday morning every September.

But

the beer is free. Area Budweiser and Coors distributors make generous

donations. The barbecued goat is tasty, and old friends enjoy seeing

each other again. Though Willie Warrior isn't fond of him, current

association president Clarence Ward is a great genial bear of a fellow.

And there, all dressed up and looking pretty, is Miss Charles, now

gaunt instead of plump but still, at age 91, able to sit on a parade

float and wave vaguely at old friends she can no longer recognize.

Most of the "floats" are just pickups dotted with flowers

fashioned from Kleenex, but Miss Charles' float is an elaborate, if

tiny, reproduction of the wood huts in which the scout families used

to live along Las Moras Creek. She sits in front of the hut on a high-backed

chair, looking regal.

After

the parade is over, everyone troops to the tiny park Brackettville

has set aside for the Scout Association. Forty-five minutes are given

over to well-meaning speakers who are more confusing than informative

when they try to pay tribute to the Seminole Negro's noble history.

Awards are given for the best parade floats, and then two staffers

from San Antonio's Institute of Texan Cultures make remarks -- at

least they get the facts right, though their presentations are more

scholarly than entertaining. With the Seminole Negro storytellers

all but gone, the institute's exhibit delineating the tribe's past

may soon be the best record that ever existed.

Through

it all, Miss Charles sits quietly on a metal folding chair in the

front row. Each speaker makes a point of praising her. When she hears

her name mentioned, she smiles and waves. At one point she's even

called to the microphone --"This wouldn't be Seminole Days without

a word from Miss Charles," somebody cries. In a reedy voice,

tottering in the warm breeze, Miss Charles says everybody looks nice.

Then she sits back down.

After

the program, many of the men head for the free beer. The women hug

each other and exclaim over dresses and jewelry. There is endless

talk involving family -- who married whom, where they might be living

now, trying to learn the whereabouts of as many third cousins as possible.

The few children in attendance amuse themselves playing on some rickety

swings and climbing bars. Even in mid-September, it is still blazingly

hot, as it has been since May. A few weeks earlier, using the weather

as an instructive example, the marquee of Brackettville's Frontier

Baptist Church noted, "Hell Is A Lot Hotter!!!" Now, Miss

Charles sits on her metal chair, perspiring but still smiling.

"So

nice to see you, Miss Charles," she is told over and over. "You

look so well."

"Thank

you," Miss Charles responds politely. Her eyes are cloudy.

Then,

gradually, the memories return. The reason she proposed Seminole Heritage

Days is somehow back, burning in her mind. Miss Charles twists a little

in her chair, looks up at the people all around, most now turned away

from her and chatting about jobs and families and who's had three

of those free beers already when, Lord, it isn't much past noon.

Seminole Woman

"Our

people . . ." Miss Charles begins. Her voice fades for a moment,

but her eyes seem to focus better, and she sits up straight and tries

again, talking to people's backs and elbows and not caring, because

the words are so important to her, it is crucial to get the story

told the right way, with all the good and bad things that happened.

"Our

people were originally from Africa," Miss Charles declares. "We

came to America as slaves hundreds of years ago. Soon many of us chose

to run away. We fled south, to Florida, and there were taken in by

the Seminole . . ." Her voice weakens. She slumps a little. But

her eyes remain bright. She is remembering. If she can just get her

breath, she'll try telling the story again.

"They

ran," Miss Charles says, softly but clearly. "They ran,

and finally they saw -- "

Chapter

One

The

first things they saw, as they followed a path through the prickly

brush into a clearing, were the fields. Corn was being grown there;

the stalks waved in the soft breeze. The air was rich with the odors

of tilled earth, animal droppings, cooking food, and oranges and lemons.

At least, that's the way it probably was. Miss Charles always admitted

she couldn't be certain what those first runaway slaves saw, or even

who they were. No records were kept then, not by escaping slaves or

the Seminole who took them in.

"But

we know they ran there and were welcomed," Miss Charles recalled

in 1994 on the first morning that I met her. We sat in the darkened

living room of her clapboard house in Brackettville. Like most houses

there, it was box-shaped with a tiny yard whose spiky grass had been

blasted a dull yellow color by the relentless sun. The living-room

curtains were drawn and only one dim light was on. As a retired schoolteacher

who had to be careful with her pension dollars, Miss Charles kept

a watchful eye on her electricity bill. Like everyone else in Brackettville,

she was already expending endless wattage that summer on air conditioning.

At 10 a.m., the temperature outside was already in the mid-90s. Miss

Charles' house was cooled by a couple of cranky window units. The

one in the living room, straining to combat the heat, groaned rather

than hummed. The noise almost drowned out Miss Charles' hushed voice.

I'd

come to Brackettville on assignment from my newspaper. Like many Texans,

for years I'd heard fragmentary tales about a black Indian tribe down

by the Texas-Mexico border. They were supposed to have helped the

Army defeat the Comanche and Apache. There were Medals of Honor involved,

and a cemetery. But for most of us, these Seminole Negro, whoever

they really were, remained more rumor than legend.

When

I finally took time to consider it, the black Indian story seemed

interesting enough to follow up. There was surprisingly little reference

material about the Seminole Negro in the downtown Fort Worth library.

From the limited sources of a few articles from scholarly magazines

and a mention in The Handbook of Texas, published by the Texas State

Historical Association, it seemed the tribe's history broke down into

well-defined sections.

Its

origin involved runaway slaves reaching Florida and being adopted

by the Seminole Indians. After the Second Seminole War, the Seminole

Negro were shipped off to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Persecuted

and miserable there, they embarked on a lengthy escape across Texas

and down into Mexico, where they fought Indians for the Mexican government.

After the Civil War, the Seminole Negro came back to Texas, where

their men served as scouts for the United States, tracking marauding

Comanche and Apache. Several scouts won the Medal of Honor. In 1914,

the army eliminated the scouts, some of whose descendants still lived

in the tiny West Texas town of Brackettville. There was just enough

sketchy information to be intriguing -- at least, enough for the basis

of a Sunday feature story and the chance to get out of the office

for a couple of days.

I

flew from Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport to San Antonio,

rented a car and drove southwest for almost two hours. The land became

progressively harsher. Brackettville, when I arrived, was disappointing.

The town itself was a small, depressing conglomeration of clapboard

shacks, roadside convenience stores and more than a few shuttered

shops that had closed for lack of business. There was a huge sign

by the highway touting Alamo Village, a vast ranch about six miles

north where John Wayne made his epic (if historically inaccurate)

movie, and where other Westerns like Lonesome Dove needing desolate,

harsh-looking locations had later been filmed. There was also a formal

entrance to Fort Clark Springs. The old military installation adjacent

to Brackettville had been turned into a combination residential community/golf

resort. I took a room at the motel there -- the charge came to less

than $40 a night -- and drove to Brackettville's tiny combination

City Hall/police station, where I asked a heavy-set Hispanic woman

at the front desk whom I should talk to about the Seminole Negro.

"That

would be Miss Charles Emily Wilson," she said immediately. "You're

from a newspaper? She's their leader. A retired teacher, you know.

Lovely lady. I'm sure she'll be glad to see you." She turned

her back and made a quick phone call. I could hear a few words --

"reporter" was emphasized. Then the woman turned around

and said Miss Charles would be glad to see me. I was given directions

to her house. They weren't complicated. Brackettville doesn't have

many streets.

Though

I'd later learn she had once been heavy, the 84-year-old woman who

greeted me now had a bony frame. She wore a print dress -- its hemline

reached halfway down her shins -- a gold necklace and just a touch

too much of the sort of sweetish perfume favored by elderly ladies

everywhere. Miss Charles -- "Call me that or Miss Wilson, but

Miss Charles will do" -- also retained a teacher's air of authority.

She invited me inside, pointed to the living-room chair where she

wanted me to sit and, after establishing which newspaper I represented

and that I intended to write a nice story about her people, said she

would tell me all about it.

"I'll

tell you just what I always tell our children," Miss Charles

said. I had to lean forward to hear her. The window air-conditioning

unit was very loud. "Do you know about our Seminole Days celebration

in September? Do you have children of your own? You could come back

then, and bring them to hear the stories."

So

Miss Charles began, saying her people had originally been slaves in

the American Colonies and that they escaped from their white masters,

ran south and were taken in by Seminole in the Spanish colony of Florida.

"When did the first slaves escape and do this?" I interrupted,

scribbling in my notebook. "In what year? What were their names?"

"Oh,

no one knows," Miss Charles replied, sounding slightly impatient.

"Who was there to write down such things? I know what my mother

and father told me, which was what their parents told them, and so

on back through the generations. Just listen to the story. For the

first part, the names don't matter much."

"Well,

do you know how many escaped to the Seminole? Just one or two at first?

Did they come in groups or separately?"

Miss

Charles was clearly not pleased. Adopting the tone she must have used

for decades with especially recalcitrant students, she said, "It's

not certain. I believe they may have come in small groups. Perhaps

six. Half a dozen. That's as good a number as any." Irritation

made her voice slightly more audible above the laboring air conditioner.

Miss Charles began her story again. On this occasion, as on the others

that followed, her reedy tone gradually took on a near-hypnotic rhythm.

She spoke with her eyes closed and her head swaying slightly, no doubt

imagining, as she always hoped her listeners would imagine, the great

saga as it unfolded.

"The

six runaways came into a clearing," Miss Charles said again.

"They looked about them, and then they saw . . ."

They

weren't certain what to expect. They fled south because, like many

blacks in American bondage, they heard there was freedom if you could

elude pursuit and get to what white men called "the Floridas."

But this substantial village surprised them; they stared at it, almost

unable to believe it could be real.

The

so-called Revolutionary War had just ended. American colonists had

overthrown British rule, but it made no real difference in the lives

of their slaves. These half-dozen Africans, all men, perhaps ran away

from a South Carolina plantation months earlier. They came more than

300 miles south, mostly moving at night, stealing food from farms

they passed, staying alert for the sound of hooves or hounds that

would indicate pursuit.

Every

unexpected noise or movement could have meant the slavers were on

them, those men with their guns and chains, eager to drag them back

to where they'd run from. Capture would have meant certain agony,

for runaway slaves could be punished at the discretion of their masters.

No law limited the severity of the discipline -- nose-slitting or

lashings that left backs permanently torn were most common. They could

each have had an ear cut off as punishment, or, if their South Carolina

master was sufficiently furious, they might have been castrated. Hanging

was less common, though not unprecedented, if a master wanted to make

a lasting impression on his remaining slaves. But these six were not

captured.

Instead,

they ran south until, finally, they came to the fabled Spanish town

of St. Augustine, revered by American slaves as the place where white

men allowed black men to be free and gave them tools for farming and

even guns to help protect Florida from invaders. These newcomer slaves

were puzzled when, with signs and broken English, it was indicated

by the white men in St. Augustine that they should keep going south

and west. They did as they were told, and there was relief in knowing

they were probably safe from any American pursuers.

And

now this! It was more than a camp, more than a village -- a town,

a much grander one than the shacks and mucky streets that comprised

many white American communities. Looking past the fields and the hog

pens, the runaways saw many long cabins built from palmetto planks

and thatched with fronds, and they somewhat resembled the huts with

leafy roofs some of these Africans remembered from their native homelands.

This

grand community was undoubtedly the Seminole town of Cuscowilla on

the Alachua Plain, 50 miles southwest of St. Augustine. I deduced

this later from old maps and history books, not Miss Charles, who,

when her tale involved early tribal events in Florida, was much less

specific than she would be regarding the Seminole Negro experience

in Indian Territory, Mexico and Texas. For purposes of pegging Cuscowilla's

location, the modern-day city of Gainesville is in approximately the

same area.

Although

the newcomers didn't know it, the Seminole were relatively recent

Florida arrivals, too. Chief Cowkeeper established Cuscowilla 30 years

earlier, making his peace with the British when they acquired Florida

from Spain in 1763. Had these slaves arrived at Cuscowilla while Cowkeeper

was still chief, in the days before the Americans won their freedom

and chased the English back into Canada or across the great ocean,

they would have had a different reception. Cowkeeper was loyal to

the British and would have returned runaway slaves to their colonists.

But in 1783, with the British reeling from the loss of their American

colonies, Spain took control of the Floridas again. Cowkeeper was

dead. His successor, King Payne, made friends with the Spanish and,

as they did, welcomed escaped blacks.

"Didn't

the Seminole make the blacks their slaves?" I asked Miss Charles.

"You'll

see," she replied, her eyes still closed, her mind still picturing

it all. "It took awhile for everyone to figure out what was what."

The

six black men were directed into town, toward the larger huts in the

center of the village. There they were formally greeted by a particularly

well-dressed man who might have been King Payne. If he didn't happen

to be present, there would have had subchiefs on hand for such duty.

The blacks felt relieved. The extent of the welcome made them hope

they would be allowed to stay. Conversation proved impossible. Besides

their own native Muskogee dialect, the Seminole may have had a few

words of Spanish. The runaway slaves probably knew some English --

white slaveowners did their best to keep slaves ignorant of anything

that might help them to escape -- and, of course, their own native

tongues, but they were not all from the same region of Africa and

had a hard enough time communicating among themselves.

Then

there was a commotion off at the north end of the village, and happy

shouting. Someone else had arrived, several others from the sound

of all the voices, and then the runaways nearly reeled with shock,

because walking up to them were other black men, dressed in the same

bright colors as the Seminole. These Indian-Blacks greeted the runaways

in an odd language that included some English. It was astonishing.

The

six newcomers were urged to their feet. Friendly hands on their shoulders

filled in gaps left by unfamiliar words. The Indian-Blacks led them

out of Cuscowilla, back into the brush, and the runaways wondered

if they were being sent away to fend for themselves. But their new

guides made it clear they were to all stay together, and there was

a path they followed through the brush and past the lemon and orange

trees until, in a clearing perhaps a mile from Cuscowilla, there was

a second village, a smaller one, but the fields and pens and herds

looked the same and the huts were bigger, built better. There was

another, more amazing sight: The men and women and children rushing

to greet them were all black, every one! Some held hoes and other

farming implements. A few men had bows and arrows. One or two cradled

muskets. Since being removed from their native lands, the runaways

had not seen black men with weapons. The sight made them proud.

There

were main huts in the center of this village, too, and the newcomers

were ushered to them. A stooped black man in bright finery stepped

out of one and walked to the runaways with his arms wide in greeting.

The

six new arrivals looked around. After so many years in bondage, it

was hard to comprehend the possibility of free black people in their

own homes. "Where are?" one runaway asked, summoning his

best pidgin English.

The

man considered."A casa ," he finally said. "Home."

And

so six runaway slaves needed to run no farther. In the days ahead,

they would be assimilated into village life. They would be given tools

to cut palmetto trees and build huts, parcels of ground for fields,

seed to sow, weapons for hunting. If they found willing women, they

could take wives. There were rules, of course, in this first camp

of the Seminole Negro, these runaway slaves who aligned themselves

with the Indian tribe. The newcomers had much to learn about their

complicated relationship with their Seminole hosts, and about the

Seminole relationship to the Spanish.

While

they forgot about their old masters for a while, there was little

chance the Americans would let their valuable property get away quite

so easily. The relative tranquility of Cuscowilla and the adjacent

Seminole Negro camp was not going to last much longer. The Americans

wanted their slaves back, and they also wanted Florida. They would

be coming soon.

In

the decades and centuries ahead, critical events in history would

often impact the Seminole Negro, almost always to their detriment.

This moment, this speck of time in the 1780s, might have been when

they were closer to happiness than before or since. Protected by the

Seminole, they were relatively safe. Their numbers grew slowly but

gradually as more escaped American slaves made their way into Florida.

They proved themselves excellent hunters, good farmers, fine builders

-- their fields yielded more crops than the Seminoles' and their huts

were built better, because in their time of bondage to the white man

they became skilled in such useful arts. Seminoles treated their slaves

better than the white man did. It is easy to understand why the Seminole

Negro valued their relative freedom so much and why, soon, they fought

desperately to keep it.

After

an hour or so, Miss Charles began to wear down. Her voice lost its

rhythm; her breathing became thready. When I suggested a break, she

didn't argue.

"Are

you here for some time?" Miss Charles asked. "Will you come

back in the afternoon?"

Part

Two

Posted

on Mon., Sep. 16, 2002

Miss Charles listens

JEFF GUINN

Star-Telegram Staff Writer

Star-Telegram photo by Ron T. Ennis -Miss Charles Wilson stands

near an unmarked grave in the Seminole Indian Scout Cemetery outside

Brackettville, Tex.

One

day in summer 1994, Star-Telegram Books Editor Jeff Guinn headed to

Brackettville, Texas, to write a newspaper story on the little-known

past of the Seminole Negro, whose descendants still live in the dusty

little town. This journey inspired his book, Our Land Before We Die:

The Proud Story of the Seminole Negro, published this week and nominated

for both the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award by publisher Tarcher/Putnam.

It is the first oral history of the Seminole Negro ever written. Guinn's

book tells of a people who sought shelter in the shadow of a tribe

whose land and welfare already hung in the balance. And yet in their

tireless journey -- from Florida to Indian Territory in Oklahoma,

on the 700-mile flight from persecution that took them across the

Rio Grande into Mexico, and then back across the Rio Grande to Texas

-- they never surrendered hope of attaining land of their own. But

that hope was continually thwarted; in 1914, after decades of dedicated,

distinguished performance as scouts in battles against the Comanche,

Apache and border outlaws, the Seminole Negro were marched at gunpoint

off the grounds of Fort Clark in Brackettville. The government had

no more use for them, or for the agreement the tribe believed had

guaranteed them land of their own in return for their service. Still,

modern-day descendants celebrate Seminole Heritage Days each year

on the third Saturday in September -- and still hope for land of their

own.

The

Star-Telegram chose to print two excerpts (the first ran in Sunday's

Life section) from the prologue and Chapter One. The Sunday excerpt

introduced modern-day tribal matriarch Miss Charles Emily Wilson,

who 18 years ago organized an annual celebration to help Seminole

Negro descendants keep their history alive with a day of parades,

barbecues and, above all, Miss Charles passing down the oral history

of her people. But now Miss Charles has Alzheimer's disease. She is

brought to Seminole Heritage Days by relatives and welcomed there

by old friends whose names she can no longer recall. Still, as other

would-be historians stumble through speeches, Miss Charles begins

remembering, and once again launches into the tale of how escaped

slaves from British colonies ran away to Florida and were taken in

there by the Seminole tribe. The Seminoles, too, practiced slavery,

although a more benign version than that of the whites.

On

Sunday, through flashbacks to his interviews with Miss Charles years

ago, Guinn took readers through the early years of the blacks' existence

among the Seminole. In today's excerpt, Miss Charles explores the

tribe's gradual disenchantment with being kept in any sort of slavery.

From

Chapter One

I

stayed in Brackettville for five days and came back again afterward.

The more I learned about the Seminole Negro, the more I wanted to

know. Besides doing my own research, I spent several mornings and

afternoons with Miss Charles in her dark living room and many more

hours with Willie Warrior, her old pupil who succeeded her as tribal

historian. They were really the only two Seminole Negro descendants

left who knew enough to be mesmerizing storytellers.

But

even their knowledge had gaps, mostly concerning the tribe's early

years in Florida. Once the great U.S.-Seminole Wars concluded and

the Seminole Negro were transferred to Indian Territory, there were

government records, many letters, and a few books and other documentation.

But of the Seminole Negro in Florida very little was recorded, and,

apparently, the early tribal storytellers didn't provide much detail.

Recourse

to history books and non-Seminole Negro historians, though, provided

me with background to more fully appreciate Miss Charles' first tales

of the anonymous half-dozen slaves, and to flesh out what she and

Willie told me later. The existence of the Seminole Negro resulted,

as most cultures had to, from merging forces of history. That there

were blacks seeking freedom; that they fled to Florida above all other

regions of the North American continent; that the Seminole tribe was

there to greet and shelter them -- these were separate elements that,

through chance or some higher design, came together in that place

and time.

Later,

when I shared what I'd learned with Miss Charles, she listened raptly,

leaning forward but usually with her eyes closed. I could easily imagine

her sorting through what she was hearing, deciding which facts could

be incorporated into her own tale-telling. It had been necessary,

I said, to go back some 350 years from the time the first slaves ran

to the Seminole in Florida. To understand all that was going to happen,

I'd needed to begin with the development and eventual collision of

three historic facts -- slavery in the New World, the colonial ambitions

of Spain and the decision by members of the Creek tribe to break away

and form their own nation.

"Oh,

yes," Miss Charles said. "Let me get some paper." She

rummaged in a desk drawer and brought out a pad and pencil. Then she

gestured for me to begin.

Slavery

came first. In 1415, Portugal became the first European nation to

actively participate in the slave trade. Spain and the Netherlands

became heavily involved. For a long time, France and England participated

to a lesser extent. In Europe, there was limited use for uneducated

African slaves. There was not an endless amount of land to be tilled

and harvested. But, across a great ocean, there were new economies

that could only flourish with an immense influx of slave labor.

Early

on in their New World colonies, the British didn't dabble in the African

slave trade. As in England, indentured servants provided the first

labor for American colonial masters. When British colonists did experiment

with slave labor, they used captured American Indians. That plan failed

miserably. The Indians were still in their homeland; it was easy for

them to escape. Members of their tribes often skulked about and stole

them back. So when Indians didn't prove suitable, and the number of

available indentured servants dropped off -- this New World was, by

wide repute, a dangerous place, and poor, young Englishmen were reluctant

to gamble on a period of indenture in return for eventual freedom

if they survived -- African slaves suddenly seemed necessary.

In

a very real sense, blacks were brought to America from Africa to die.

Three or four Africans in 10 died on the slave ships crossing the

Atlantic Ocean. On average, the slave who survived the voyage lived

five years after arriving in the British colonies. Measles and influenza

killed them. Living in shanties and rough lean-tos, many died of exposure.

Some were worked to death, with no more value assigned to their lives

than those of mules that dropped in the traces of a plow. A percentage

died from beatings, and it was not unknown for slaves to commit suicide.

So

slaves faced hard choices. Once sold to an owner and put to work on

his property, each captive African could, of course, accept his or

her sad fate and work resignedly until freed by death. Fighting back

was almost certainly fatal. A single armed slave was easy for whites

to subdue and execute; rebelling in a group only meant more Africans

would die. Trying to run away, individually or as part of a group,

was also risky. Recapture would certainly mean terrible punishment,

and even if white pursuers could be eluded, there were hostile Indians

everywhere who might either kill Africans or enslave blacks themselves.

But

among the three choices -- work until death, fight until death, run

until captured or free -- one had, in modern jargon, the best upside.

The healthiest, strongest slaves looked for chances to run away. The

potential penalties for a failed escape -- beating, mutilation, even

execution -- weren't that much worse than everyday pain endured in

the fields. So, many slaves tried to run.

"How

many?" Miss Charles asked. "I don't know," I admitted.

"Most people then didn't keep accurate records."

"I

told you," she said, grinning. "But they all wanted to come

south, didn't they? To Florida."

Africans

fleeing masters in northern colonies could try for Canada. But there

were fewer blacks in the north, and towns were closer together. There

was less room to hide, and dark skin was more conspicuous. To the

west were the Allegheny Mountains, and Indians who were as dangerous

to runaway slaves as the masters they were fleeing. To the east was

the Atlantic Ocean -- no hope there.

But

to the south was Florida, territory of the Spanish, and many black

slaves in the British colonies dreamed of escaping to Florida, where

Africans were allowed to be free.

From

the moment in October 1492 when Christopher Columbus and his crew

spied land -- not mainland America, of course, but an island, which

Columbus named San Salvador -- the Spanish were eager to conquer and

occupy as much New World territory as possible. While the British

wanted land and the French pursued trade, Spain wanted everything,

especially the fabulous treasures its explorers believed were waiting

to be taken from the native people who had accumulated them.

In

the so-called New World, Spain concentrated on Mexico -- "New

Spain"-- and the north and west South American coasts (there

was an agreement with Portugal that left the interior of South America

for Portuguese occupation). But the Spanish had one other colonial

holding.

In

1513, Juan Ponce de León landed near the spot where, one day,

Jacksonville would be built. Having come to the New World as a member

of Columbus' first colony on Hispaniola, Ponce de León had

a grant from the king to find and settle additional new lands, with

any natives being forced into slavery and given as property to Spanish

colonists. Not an especially observant explorer, Ponce de León

thought he had landed on an island. He sailed his ships south and

west, charting a unique, finger-shaped coastline, and named the "island"

Florida.

Spain's

main colonial focus was elsewhere. New Spain and its South American

holdings held the promise of gold, or at least access to further vast

expanses of land to conquer. Florida was oddly shaped, cratered with

swamps, and full of angry natives who declined to be conquered. But

Spain needed Florida. England was in the process of establishing colonies

all down America's Atlantic coast and extending west with the colony

named Georgia. Spain required its own foothold in this portion of

the American continent.

In

1565, King Philip II's colonists built St. Augustine on the east Florida

coast between the Atlantic Ocean and the St. Johns River. The settlers

there were able to stave off initial Indian attacks and gradually

began making friends with the natives. Catholic priests were sent

to St. Augustine with specific instructions to bring red-skinned heathens

to Christ, but soon lacked potential converts. Florida Indians seemed

especially vulnerable to European diseases. Within a few years, these

native tribes -- the Tocobaga, Chilucan, Yustaga, Oconee, Pensacola

and several others -- virtually disappeared. Perhaps 1,000 American

Indians were left in all of Florida.

Spain

allowed its Florida colonists to own black slaves. The few remaining

American Indians were tolerated, not annihilated. The central Florida

plains offered some opportunity for farming, and game was plentiful.

Besides deer, there were bear and wild pigs and even panthers. Lush

citrus fruit was readily available. It became apparent Florida had

great potential as a place to live, raise crops and hunt. The quirky

Florida coastline offered all sorts of possibilities for ports. Fishing

in its coastal waters was prime.

None

of this escaped the notice of English colonists who spread down the

Eastern seaboard. Settlers in South Carolina and Georgia felt no obligation

to stop moving south. As more slaves were imported into these British

colonies, their owners had greater interest in expanding their land

holdings. In the 1680s, British colonists in Georgia and the Carolinas

approached the Creek nation, one of the largest among all American

Indian confederations, with the suggestion that the Creek raid Spanish

settlements in Florida. The Creek were well-organized and essentially

autocratic. Chiefs -- called miccos -- required taxes from their subjects,

using the crops collected in this way to benefit poorer tribal members.

The Creek also kept slaves, including some Africans sold or given

to them by white colonists. The British/Creek alliance was a substantial

danger to Spanish Florida.

Since

the British and Creek made a habit of raiding Florida, the Spanish

wanted armed manpower more than slave labor. They not only welcomed

escaping slaves, they encouraged them to send word back to the Carolinas

and Georgia that there were opportunities in Florida for runaways

to be completely free. They would have to take instruction in Catholicism.

And they would, of course, have to be willing to bear arms on behalf

of their new Spanish friends.

In

1704, Gov. Jose de Zuniga y Cerda of Florida's Apalachee Province

declared that "any negro of Carolina, Christian or not, free

or slave, who wishes to come fugitive, will be [granted] complete

liberty, so that those who do not want to stay here [in this area

of Florida] may pass to other places as they see fit, with their freedom

papers which I hereby grant them by word of the king."

Miss

Charles asked me to spell the governor's name for her. When I did,

checking it carefully against my notes, she wrote it down on her own

notepad. I asked why she wanted to know.

"I

know about Ponce de León, of course," she said. "But

not this Governor Cerda. Now, if one of our children asks me about

him, I can answer."

"I

don't think any of them will ask you that," I said.

"Children

are a wonder," Miss Charles replied. "Someday, one of them

might."

In

February of 1739, Florida Gov. Manuel de Montiano built a coastal

fortress a few miles north of St. Augustine. He invited free blacks

to populate it; Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, more commonly

known as Fort Mose, was the first free black community in North America.

Spain did its best to make Fort Mose attractive to Africans. Seed

and tools for farming were provided, and food was sent in until the

first crops could be raised. There was a priest assigned to the fort

for religious instruction. Cannon were placed on the ramparts. Muskets

were issued to men who wanted them, and most did. The only obligation

placed on the Africans living there was to help defend Florida against

invaders.

Word

about Fort Mose spread quickly to slaves in the southern British colonies.

The colonists and the English army personnel stationed in the southern

regions of their American colonies decided they had only one option

-- to invade Florida, destroy St. Augustine and Fort Mose, and, they

hoped, drive out the Spanish colonists forever. All they needed was

an excuse.

In

October, they got one. Britain declared war on Spain over Spanish

harassment of English shipping. It was known as the War of Jenkins'

Ear, because British sea captain Robert Jenkins supposedly had his

ear hacked off by Spaniards near the coast of Cuba. British colonists

in America marched south into Florida and attacked St. Augustine.

They were amazed to find the city's

defenders

included several hundred black soldiers. The Africans received the

same pay and benefits as Spanish enlistees and fought under the command

of black officers.

Though

St. Augustine withstood the attack, Fort Mose didn't. Enough of its

buildings were destroyed that the Africans living there had to be

relocated to St. Augustine. It was 1752 before it was rebuilt and

became an African stronghold again.

Britain's

colonies in the New World eventually had trouble on two fronts. In

1754, the extended French and Indian War broke out between the English

and French. England was trying to extend its colonies west of the

Allegheny Mountains, and the French felt they already had claimed

the land there.

Even

with the British also fighting France, and even with its contingents

of black soldiers, Spain was still handicapped in efforts to retain

Florida. Colonists in Georgia encouraged the Creek to stage hit-and-run

attacks on Spanish colonies; the Creek especially welcomed the raids

because it enabled them to capture Africans who would serve as tribal

slaves.

Eventually,

the Treaty of Paris in 1763 temporarily ended both the English-Spanish

and English-French conflicts. But by the time the War of Jenkins'

Ear was over, there was a new player in Florida, perhaps the critical

mass in the violent explosion of war that would come 50 years later.

"This

is where the Seminole come in, isn't it?" I asked Miss Charles

on my first day with her.

"I

know something about that, but Willie Warrior knows more," she

said. It was late in the afternoon. After leaving Miss Charles earlier,

I'd looked round Brackettville to find someplace to eat. I knew there

was a restaurant on the old fort grounds near my motel, but I didn't

want to drive back across the highway. Instead, I cruised the limited

blocks of Brackettville and found exactly one cafe. It was called

the Krazy Chicken. The menu consisted of a few things fried in grease.

I ate a hamburger there and was immediately sorry. Afterward, I poked

around town, killing time until I thought Miss Charles had sufficient

time to rest. I passed one grocery and two video stores. There was

a small public library, but no bookstore or movie theater.

When

I got back to her house, the temperature outside was well over 100

degrees. The air conditioner in the living room window couldn't compete

with such heat. The air inside was warm and sticky. Miss Charles blotted

herself with a Kleenex.

"Willie

and some girl from a college were talking about where the Seminole

got their name," she said. "She was telling him things,

and he was laughing at her. I think he said nobody knows about the

name, they just think they know. Have you talked to Willie yet?"

I

said I was going to see him the next day in Del Rio, a town some 30

miles west of Brackettville. I'd called from a pay phone outside the

Krazy Chicken -- the helpful woman at City Hall had given me his phone

number, too. A man with a deep voice on the other end of the line

identified himself as Dub Warrior, and when I asked for Willie Warrior,

he said that was his name, too.

"He's

a good one," Miss Charles said proudly. "He and his wife,

Ethel, are both in the Scout Association. He goes to schools all the

time to give talks. He can tell you all about the Seminole."

Historians

have argued for years where the name Seminole comes from. Some believe

it is a bastardized term from the old Creek language. Others insist

it is a corrupted pronunciation of the Spanish word Cimarron. Most

agree Seminole is suppose to mean runaway. What is important is why

there was a newly formed Indian conglomerate known collectively as

the Seminole, because it would directly affect the eventual relationship

between the Seminole and the black runaways the newly hatched tribe

took in.

Early

in the 1700s, the Spanish realized they needed more inhabitants in

the Florida lands between Georgia and the Carolinas and St. Augustine.

This would make it more difficult for the English colonists to conduct

raids. Runaway slaves weren't numerous enough to occupy sufficient

territory. Prospective Spanish colonists were mostly sent to New Spain

and South America. So the same European power that gleefully slaughtered

natives by the hundreds of thousands in New Spain rolled out the proverbial

welcome mat in Florida to Indians who wanted to come and live there.

As it happened, there were some Indians who were pleased to be invited.

Small

bands began breaking away from the Lower Creek nation; these pushed

south and east into Florida. Various struggles between colonists and

Indians to the north drove additional American Indians south. So long

as they would comply with Spanish rule, they were welcome in Florida.

Chief

Cowkeeper and his Oconis established primacy among the newcomers,

who were also joined by surviving members of Florida's indigenous

tribes. A less stringent form of Creek government was enacted. Each

village chief could assess taxes from crops and generally oversee

daily life. Designated from among the village chiefs would be a few

principal chiefs, who collectively would make decisions on behalf

of the entire tribal nation. "Nation" might give the impression

of greater numbers than were initially in Florida. Perhaps 2,000 Seminole

lived there by the end of the 1700s. The tribe's numbers continued

to swell as more Indians left the Creek and migrated east.

These

newcomers were allowed to build on land unoccupied by the Spanish.

Unlike many tribes in the western plains and Southwest, the Seminole

built permanent villages. They meant to stay. They were primarily

farmers and hunters.

And,

from the beginning of their Florida existence, the Seminole had slaves.

Their system of vassalage was more benign than that of the Creek.

Slaves, captured in battles with other tribes, had their own lands,

huts and weapons. They were required to give a portion of their crop

to their owners. Slaves and owners intermarried, most often Seminole

men and slave women. Monogamy was not required of Seminole males.

Different

tribes joining to form the Seminole nation spoke different languages.

It would be the 1820s before the Muskogee tongue of the Lower Creeks

became the most common means of verbal communication. They learned

some Spanish, too, but in 1763 they abruptly needed to learn English,

when European powers met, negotiated and ended up trading large tracts

of land in the New World. Spain received the French holdings west

of the Alleghenies. Spain also received Cuba from England. England

got Florida from Spain.

Immediately,

the Spanish shipped most of their black Floridian allies off to Cuba

and other island holdings. English colonists from the Carolinas and

Georgia rushed into Florida searching for runaway slaves, and some

were recaptured. But many black refugees stayed in the Florida swamps;

other freedmen booked passage to Spanish islands in the Caribbean.

As

English settlers swarmed in, they brought slaves with them. The British

made friends with the Seminole, who had no reason to particularly

miss the Spanish. The Indians noted how ownership of Africans conferred

social status on English owners. The richer Seminole began to buy

occasional black slaves for themselves. The British also made a habit

of awarding slaves to various Seminole chiefs. These were known as

"King's gifts."

From

the beginning, the Seminole had to decide what to do with their slaves.

They certainly had no intention of imposing the same harsh rules as

the white men and Creek did. The Seminole-owned Africans were given

tools and instructed to build huts of their own, in villages adjacent

to but separate from those of the Indians. The blacks had seed to

plant their own crops. Some even received a few cattle or pigs to

start their own herds. They were expected to share part of their harvests

with their owners, but in all, blacks quickly discovered that being

a slave among the Seminole was far preferable to white man's bondage.

On a daily basis, they were as free as the Seminole themselves, and

most often called Seminole Negro -- Black Seminole.

Word

of this spread among slaves still held in the Carolinas and Georgia,

and to slaves of white masters in Florida. These Africans kept running

away, running south and east -- but now they were running to the Seminole,

not to the Spanish. Some of the chiefs who were especially loyal to

Britain, Cowkeeper in particular, returned runaway slaves. But other

chiefs didn't.

The

outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1776 uprooted many landholders

in the Carolinas and Georgia who had remained loyal to the British.

These people -- and their slaves -- took refuge in Florida. But in

the Caribbean and other places, the French and Spanish fought the

British as well. It was only in 1783, with yet another Treaty of Paris,

that all hostilities in the New World ended, at least for a little

while. Once again, the European superpowers traded colonial holdings,

and this time the new American nation also was a participant. And,

while America gained certain fishing rights off the Newfoundland coast,

and other rights regarding passage and exploration along the Mississippi

River, there was one aspect of the treaty that infuriated Americans,

particularly those with land and slaves in Southern states. Spain

had taken Florida back from Britain.

This

meant that runaway slaves were welcome in Florida again. Spain had

no particular stake in the prosperity of the so-called United States.

While America had won its freedom from Britain, the fledgling nation

was far from a global superpower. Spain intended to hang onto Florida

this time.

"This

is where you always start your story, Miss Charles," I said one

afternoon as we sat in her living room. I can't remember what time

of year it was, but the window air conditioner was emitting its usual

roar because it was so hot outside. It almost always is hot in Brackettville.

"Yes,"

she replied sleepily. It was obvious she was tired. I offered to leave,

but she said she wanted to "visit" a little more. "It

happened just like I told you, didn't it?" she asked.

"Just

like you said," I agreed.

The

Spanish began encouraging runaway slaves to go to Seminole villages.

The Indians' lenient tribal system of vassalage suited Spanish aims

perfectly. The blacks would be part of the Seminole, and the Seminole

could help fight Americans if and when it became necessary. By aligning

the Indians and Africans, Spain increased its defenses without having

the responsibility of providing for the runaways.

Outraged

American slave owners in the South did what they could to retrieve

their human property from Florida. They entered into new treaties

with the Creek, and those chiefs promised to return the Florida runaways.

The problem, of course, was that the Seminole now considered themselves

separate from the Creek and in no way bound by that tribe's agreements.

Such Seminole recalcitrance worsened relations between the tribes.

Blacks

living with Indians or in their own camps were commonly called "Maroons"

by the whites. In some history books, the Seminole Negro are identified

only as Maroons. They were also called Black Seminoles or Black Indians.

But Seminole Negro -- the latter word pronounced NAY-gro, not NEE-gro

-- seemed to suit them best.

Early

letters and trading documents describing visits to Seminole Negro

villages describe inhabitants as hard workers. Certainly, the life

they had in Florida with the Seminole was infinitely better than existence

as slaves of white men on their Southern farms and plantations. But

they weren't entirely happy. They were better off than before, but

they still belonged to someone else. They were still property . And

the Seminole, though benevolent masters, had no intention of ever

giving up the slaves they owned.

The

most telling measure of the very real division between the Seminole

and Seminole Negro was the separation of their villages. There was

always space -- a mile, two miles -- between them. Put simply, the

Seminole Negro were considered allies, but not blood kin. The Seminole

clearly felt themselves to be superior.

Such

class distinctions developed over the years. The Seminole Negro spent

these relatively quiet times assimilating some of the Seminole culture

and developing their own. In particular, they gradually created their

own language, Gullah , a mixture of English, Spanish and various African

dialects. Slaves on America's southeastern seaboard also formed variations

of Gullah, and future linguists would spend entire careers rooting

out the origins of individual words.

Seminole

Negro religion incorporated aspects of African faiths, Indian beliefs

and American Christianity. Through the addition of runaways and some

intermarriage with the Seminole, the tribe grew more numerous. Eventually

there were several Maroon towns in northern Florida and along the

Alachua Plains. Perhaps, if left alone, the Seminole Negro would have

indefinitely stayed allied with, but subservient to, the Seminole.

They might eventually have declared their freedom in much the same

way the Seminole separated from the Creek. Certainly there were Maroon

communities in the Caribbean where they would have been taken in,

or they might have established their own lands farther south along

the Florida peninsula, somewhere the Seminole hadn't yet reached and

the Spanish settlers didn't want. But there wasn't enough time for

such possibilities to play out, because a decade into the 1800s, America

decided to take Florida away from Spain, precipitating tragic events

that followed one upon another like bloody footprints across history.

"All

that happened so long ago," Miss Charles commented late in our

first day together. "That's why our kids at Seminole Days don't

want to listen. They think if something's old, it's not important."

Later,

when I'd learned more about her own remarkable history, I thought

Miss Charles could have spent that first day telling me all about

herself -- how she became the first scout descendant to go off to

college, how she earned not only an undergraduate but a graduate degree

as well (this in a time when young black women rarely completed high

school), how she'd spurned opportunities for life in big, exciting

cities to come home to seedy Brackettville and work with her people

there. Miss Charles not only ruled the Scout Association, she'd founded

it. She not only survived segregation in Brackettville, she was eventually

named the town's citizen of the year. Charles Emily Wilson was one

of the first black teachers in Texas to teach integrated classes.

All this, and the only personal reference she made that first day

was how, as a 4-year-old child, she'd cried in 1914 when the Army

marched the Seminole Negro off Fort Clark grounds at gunpoint.

"Willie

Warrior will tell you interesting things in Del Rio tomorrow,"

Miss Charles promised as she escorted me to her front door. "What

we've talked about today is only the beginning of my people's history.

Come back after you've seen Willie."