Jack Hays

In his book, Texas Rangers, Walter Prescott Webb

describes Hays:.

John C. Hays, known in Texas as Jack Hays, was born at Little

Cedar Lick, Wilson County, Tennessee, on January 28, 1817. He was

from the same section of the country as the McCullochs, Sam Houston,

and Andrew Jackson, and was the same adaptable sort of person. It

is said that Jackson purchased the Hermitage from Jack Hays's grandfather,

John Hays, who served with Jackson in some of his Indian wars, and

who built Fort Haysboro. Jack's father, Harmon Hays, also fought

with Jackson and named his son for General John Coffee, one of Jackson's

trusted officers.

Andrew Jackson. From a painting in New York City Hall.

In his book, Men Who Wear The Star, Charles M.

Robinson, III includes Ranger Lockhart's description of his captain:

In the dry and rocky portions of West Texas a squad of fifteen

or twenty Indians could go through the country without leaving much

sign, consequently a trailer was considered a very effective man.

This faculty Captain Hays had to a very marked degree, it almost

amounted to instinct with him; he could ride along at a good pace

and see the signs where other men could see nothing, hence his great

tact in overhauling and finishing Indians. It is said that often

he could dismount and observe the small pebbles, and by noticing

the slightest displacement made by the horses, could, in a moment,

tell in what direction they had gone.

Webb also quoted Hays' Lipan Apache scout, Flacco:

"Me and Red Wing not afraid to go to hell together. Captain

Jack heap brave; not afraid to go to hell by himself."

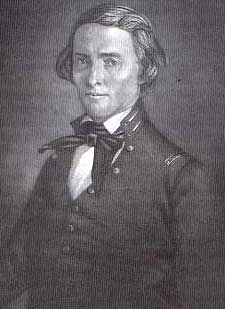

Captain Jack Hays

About 1844, Kit Ackland, Mike Chevalier, Creed Taylor,

Noah Cherry, an Irishman named Paddy, and others, under the leadership

of the brave and bold John C. (Jack) Hays, made an expedition up the

Nueces River in search of Indians. But no Indians were found, so the

rangers started home. After traveling for a considerable distance, someone

about noon discovered a bee tree, and the point of entrance of the bees

was a considerable distance, someone about noon discovered a bee tree,

and the point of entrance of the bees was a considerable distance from

the ground. Noah Cherry took a small axe and ascended the tree to get

some honey; and his position gave him a splendid perspective of the

surrounding country. At a moment when least expected he sang out, “Jerusalem!

Captain, yonder comes a thousand Indians.” Since they were coming

at a rapid gait, Captain Hays who was sitting on the ground, jumped

to his feet and exclaimed, “Come down from there quick! Men, put

on your bridles, pick up your ropes. Be ready for them! Be ready for

them! The rangers were armed with two colt five or six shooters, a rifle

and a holster single-shot pistol.

Captain Jack Hays has been credited with having never

lost a single Indian battle, although he was almost invariably greatly

outnumbered. On this occasion, he had fourteen men, and they were charged

by approximately two hundred Comanche warriors. The Indians, thinking

that such a small number would be easily routed, came charging and yelling

like wild demons. Captain Hays cried out, “Now, boys, don’t

shoot too quick; let them come closer; hit something when you shoot,

and stand your ground. We can whip them, there is no doubt about that.”

When the citizens fired, the Indians who were at close range, lost several

of their number, and many of their horses were also wounded. Indeed,

they were surprised that the few whites were still standing their ground,

so the remaining Indians divided and were making an effort to strike

them from each side. Capt. Jack Hays instantly sprang into his saddle,

and shouted, “After them boys; give them no chance to turn on us;

crowd them; powder burn them.” The Indians fully expected the rangers

to assume the defensive, and in a short time, cause them to exhaust

their ammunition. Evidently never before had this particular band of

Indians encountered rangers using the five shooters. Such weapons of

war with which they had previously come in contact were single shooters,

and this new weapon had only recently been invented. So, when Hays and

his men boldly charged into their very midst, the Indians although they

outnumbered the whites nearly fifteen to one, became completely confused,

demoralized, and being unable to rally their forces sought safety in

flight. Some of them dropped their bows and shields, and other implements,

while trying to dodge the flashing pistols. The Comanches were charged

for about three miles, by the rough and ready rangers. In this mad rush

for life, some of them prevented the rangers from really powder burning

them, only by the force of their lances. Brave Kit Ackland followed

the captain’s orders closely, in trying to powder burn the Indians

and he was lanced on three different occasions.

When the fight was over, and the rangers rode back to

their bee tree, the Irishman Paddy, said he saw a wounded Indian go

in a certain thicket and that he was going in there after him. Capt.

Hays exclaimed, “If there is a wounded Indian in there, you had

better let him alone. If you go in where he is, he will kill you before

you see him.” But he persisted in going, and was pierced through

the heart by the wounded warrior. Three or four of his companions cautiously

advanced to his aid. When the first movement of the wounded Indian became

discernible, each of them fired and upon examination, it was found that

none of them had missed their mark. Poor Paddy, however, lay dead with

an arrow through his heart, and he was buried nearby.

Jack Hays

Many years afterwards, the Comanche chief who led his

warriors on this occasion, asked a friendly Delaware who it was that

made so brave a fight on this occasion. The Delaware replied, that it

was Captain Jack Hays, and his Texas Rangers. The chief shook his head

and said that he never wanted to fight him again, for his men had a

shot for every finger on his hand, and that the Comanches lost half

of their number. He also stated that the warriors died for a hundred

miles back towards Devil’s River.

About 1844, while scouting in the present Gillespie County,

Capt. Jack Hays in charge of a detachment of fourteen men, discovered

about fifteen Comanche warriors who showed signs of wanting to fight;

but Hays realizing that the Indians, no doubt, were endeavoring to ambush

the Texans, led his men around the timber and stationed them on a ridge,

separated from the Indians by a narrow valley. The Comanches realizing

that their strategic maneuvers had failed to decoy the rangers about

seventy-five in number rode out into the open, and summoned Captain

Hays and his men for a fight. The challenge was accepted and the rangers

slowly rode down the hill in the Indians’ direction. But contrary

to expectation instead of charging in front, they followed a ravine

and charged the Indians in the rear. This, of course, somewhat demoralized

the Indians, who nervously awaited the first appearance of the Texans

from the opposite direction. The Indians, however, soon rallied and

made a countercharge. Captain Hays ordered his men to be ready, and

they waited until the Indians were almost within throwing distances

with their lances, before they fired a single shot. Twenty-one warriors

almost immediately fell from their horses, and the Indians fell back

in confusion. The rangers in turn charged the retreating savages. Charge

after charge was made by both the Indians and rangers; and the fight

lasted nearly an hour. The Texans had almost exhausted their loads in

both revolvers and rifles. Capt. Jack Hays asked who was loaded. Ab

Gillespie replied that he was, and Hays told him to dismount and made

sure work of the chief as that would, no doubt, end the fight. Although

the ranger was badly wounded, he tumbled the chief from his horse. The

Comanches now retreated and when the smoke of battle had cleared away,

thirty dead Indians remained to indicate the accuracy of the Texans’

deadly aim.

In his book, Indian Depredations in Texas, J.W. Wilbarger provides a description of Hays' victory:

Enchanted Rock

On one occasion when Capt. Jack Hays and about twenty

members of his company were scouting in the vicinity of the Enchanted

Rock, Hays became separated from his companions. At an unexpected moment

he was charged by Indians, and as a consequence, retreated to the Enchanted

Rock. Hays was pursued by the Indians until he reached the summit of

this great wonder of the southwest. Here he entrenched himself in a

crevice and intended to sell his life as dearly as possible. He did

not fire until it became absolutely necessary, and when he did, an Indian

hit the granite. Again and again it became necessary for him to fire,

and nearly every time other Indians were desperately wounded or killed.

For a time the Indians, who were losing heavily, fell back, and this

gave Captain Hays an opportunity to re-load his firearms. And in this

manner for sometime, he made a desperate fight for his life. His comrades

were having a fight of their own near the bottom of the Enchanted Rock,

but could hear the firing of their Captain and screaming of Indians

near the crest of this wonderful structure. As rapidly as possible they

fought their way in his direction, and so deadly was their fire, the

Indians were soon forced to flee. Those warriors who had surrounded

the Captain, now saw the advance of the rangers and immediately retreated

to the opposite side of the Enchanted Rock. Consequently, Capt. Jack

Hays and his men were soon again together, and another victory was added

to the lists of this noble Indian fighter and his men. After the smoke

of the battle had cleared away, five or six Indians lay around the spot

where Hays had fought, and twice the number were found below. Three

or four rangers were seriously, but none fatally wounded. The exact

date of this fight is not known, but it occurred about 1844 or 1845,

and is reported at this particular time.

J.W. Wilbarger's version of the fight appears below. (From the book Indian Depredations in Texas)

Different accounts do not agree concerning the date

of this engagement. According to one account, it was fought in the

spring of 1841, while others place the date in 1843. Nevertheless,

the story will be related at this time.

Soon after the big raid of the Comanches on Victoria

and Linnville, President Houston felt a stronger need for frontier

protection. So he appointed Capt. John C. Hays to recruit a company

of rangers. Many noted Indian fighters saw service in Capt. John Hays’

company. Among the number were: Big Foot Wallace, Ben Highsmith, Creed

Taylor, Sam Walker, Ed Gillespie, P. H. Bell, Kit Ackland, Sam Luckey,

James Dunn, Tom Galberth, Geo. Neill, Frank Chevallier, and others.

When the famous fight of the Bandera Pass was fought in about 1843,

some of Capt. Hays’ best men at the time, were prisoners in Old

Mexico. But on this particular occasion, Sam Walker, Ed Gillespie,

P. H. Bell, Ben McCulloch, Kit Ackland, Sam Luckey, James Dunn, Tom

Galbreth, Geo. Neill, Frank Chevallier, and others, numbered among

the fighting forces. Hays and his men arrived at the Pass about 11

o’clock in the morning and were unexpectedly charged by a large

band of Comanches. At first his men became somewhat demoralized by

the sudden shock, but the voice of the brave Captain cried out, “Steady

there, boys, dismount and tie those horses, we can whip them. No doubt

about that.” The Colt five and six-shooters had just been invented

and Captain Hays and his men were fortunate to acquire fifty or sixty

of these weapons, which were apparently unknown to the savages. Although

many times outnumbered, the Texans began discharging their rifles

and new pistols, and every shot seemed to strike an Indian. Sam Luckey

was soon wounded and as he fell, Ben Highsmith caught him and laid

him down easy on the ground. He immediately called for water which

was tendered by Highsmith out of the latter’s canteen. The Comanche

chief during the thickest of the fighting, charged and wounded Sergeant

Kit Ackland. Ackland then wounded the chief with his new pistol, and

immediately following the two clinched and went to the ground. Both

of the men were large and fought a terrific combat with their knives.

Over and over they rolled, but finally the ranger was successful in

the duel. Covered with blood and dirt, he then arose from the ground

where lay the chief literally cut to pieces. This engagement of Captain

Hays and his men was one of the most bitter and bloody battles ever

fought in the West and continued until the Indians finally ceased

fighting and retreated to the upper end of the Pass, leaving the rangers

in charge of the battleground. Five rangers, however, lay dead on

the field, and others wounded. A large number of horses were also

killed and their bleaching bones could still be seen in this famous

old Pass for many years afterwards. After the Indians had retreated,

Capt. Hays and his men withdrew to the south entrance of the mountains,

and the night was spent burying the dead and treating the wounded.

During the same time, the Comanches buried their chief near the others

end of the exit through the mountains.

The above stories are from the book, The West Texas

Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

The Texas six-shooter was first made famous by a Ranger

captain named Jack Hays. John Coffee Hays was a Tennessean, from the

same county as Andrew Jackson and Sam Houston; in fact, his grandfather

had sold Jackson the Hermitage estate. Hays was a born adventurer,

of the type called forth by many frontiers. He went west to Texas

as a surveyor, was mustered into a ranging company, and suddenly found

his métier. Hays was a natural warrior. He was soon recognized

as the captain of his band, and, at the age of twenty-three, he commanded

the San Antonio station, the most dangerous and important Ranger post

in western Texas.

Jack Hays was the prototype for a certain kind of emerging

American hero. He did not look like a fighting man's hero: he was

slight and slim-hipped, with a clear, rather high voice; he had lovely

manners and was seen as a "perfect gentleman" by the belles

of San Antonio. Hays was utterly fearless-but always within the cold,

hard bounds of practicality, never foolhardy. He was not a talker, and

not even a good gunman, but a born leader of partisans who by great

good luck had been born in the right time and place. Hays was calm

and quiet, almost preternaturally aware of his surroundings and circumstance,

utterly in control of himself, and a superb psychologist, in control

of all the men around him. His actions appeared incredibly daring

to other men who did not have Hay’s capacity for coolly weighing

odds. It is known that most of the other Ranger leaders, and hundreds

of future riders, consciously tried to "be like Jack Hays"-strong,

silent, practical, explosive only in action. He put an indelible stamp

on the force that was soon to be formalized as the Texas Rangers.

He personally trained the great captains Ben McCulloch

and Sam Walker, and his image and example deeply influenced McNelly,

Jones, and Rogers. His example made individual Rangers into one-man

armies.

Hays was the first captain in Texas to recognize the

potentialities of Colt's newfangled revolvers. Because of this, in

early 1840 he fought the first successful mounted action against the

Pehnahterkuh Comanches. Riding beside the Pedernales River northwest

of San Antonio with only fourteen men, Hays was ambushed by a party

of some seventy Comanches. Previously, the standard Texan tactic was

to race for cover and hold off the horsemen with their long rifles-heretofore,

the only hope for survival. Hays, however, wheeled and led his men

in a charge against the howling, onrushing horse Indians; the fourteen

rangers rode through a blizzard of shafts and engaged the Comanches

knee-to-knee with blazing revolvers. Hays lost several men to arrows-but

his repeating pistols struck down a dozen warriors.

Startled, amazed by white men who charged and whose

guns seemed inexhaustible, horrified by heavy losses, the Comanche

war band broke and fled. The Rangers killed thirty Comanches.

The engagement was quickly celebrated along the frontier:

"the best-contested fight that ever took place in Texas,"

in one observer's view. Hays immediately realized that the revolvers,

plus the element of surprise, gave him a great advantage over the

raiders. He resolved to patrol boldly and to meet the enemy on horseback

at every opportunity.

Only a few days afterward, Hay’s company ran into

a vastly superior force of Pehnehterkuh in the Nueces Canyon west

of San Antonio. Hays allowed the warriors to charge, sweep around,

and completely surround him, while his troop dismounted. Then he ordered

his men to discharge their rifles, with deadly effect, and as the

exultant enemy, sure that the white men were now at the Indians' mercy,

swirled in for the kill, he mounted and led a point-blank assault.

Each Ranger singled out a Comanche warrior and rode after him. The

tactic was so surprising that the Texans were at close quarters before

the Comanches reacted.

Hays screamed: "Powder-burn them!" His riders

ripped though the Comanche circle, knocking down warriors left and

right. Enraged, the Comanches swarmed after the Rangers, believing

that they were now fleeing with empty weapons. Hays wheeled about

and charged through them again, fire spitting from his men's pistols,

shooting down the enemy before they could notch bowstring to arrow.

The Comanches, ponies and riders, were thrown into immense confusion.

Again, the Texans singled out individuals, rode beside them cheek

by jowl, and shot them out of the saddle at pointblank range.

Now there occurred that phenomenon that the whites were

to see again and again in the coming years, and which the canny Ranger

captains were to use to their deadly advantage. In the face of something

they could not fully understand-immediate bad medicine-the bravest

of warriors' morale cracked. More of the milling Amerindians were

blasted from their horses by guns that never emptied, the Comanches

became panic-stricken. They screamed and fled as if pursued by Furies.

Great warriors threw away useless shields and spears and rode away

howling, bent low over their horses' sides for protection. In their

flight the Comanches suffered far greater losses than they would have

taken had they pressed the fight. Hays pursued them mercilessly, killing

all he could overtake.

Even after the exhausted Rangers broke off the chase,

the remnants of the war band fled on to the Devil's River, more than

a hundred miles to the west. Fatally wounded warriors fell out and

were abandoned all along the trail. Fully half of the Comanches died,

and the survivors were gripped with superstitious horror. The war

chief, who lived, swore hysterically that he would never face Hay’s

Rangers again.

Samuel Walker

Ranger Walker traveled to New York at his own expense to visit Colt.

He persuaded the gun manufacturer to produce a heavier version of

his repeating pistol which would be a .45 calibre six-shooter as opposed

to the .32 calibre five shot version that had been used at Bandera

Pass. The result was a Walker Colt Revolver. The first shipment was

sent to the Ranger forces fighting in the Mexican War.

Hays gave himself no credit; he credited only the Colt

revolvers. This was, of course, too modest, yet the six-shooters did

permit white frontiersmen to meet and match Plains Indians at their

own mode of mounted warfare. Hays and his band were the new breed

of Anglo-American fighting men who had been bred in the West, audacious

and coolly competent, ready to seize any advantage and exploit it

to the hilt. Hays wrote no books and held no classes, but, by example,

he was instructing every Indian fighter near the plains. Incredibly,

almost all that is known of his exploits comes from brief, admiring

mentions by equally inarticulate contemporaries. These, however, show

what he accomplished against the Amerindians.

Hays now took the offensive, riding with confidence

into Pehnahterkuh country. He never commanded more than fifty riders,

but he had learned almost everything there was to learn about Comanche

war warfare. He picked up much from his Lipan scouts, but he also

taught them a few things. He made cold camps and rode silently by

moonlight, like Indians on the war trail, seeking out the Pehnahterkuh

in their scattered lodges and secluded but vulnerable encampments.

Now he hunted Indians. He had learned how to find them, even when

hidden in the most inaccessible canyons, by watching carefully for

the swirl of vultures that followed Comanche lodges. The buzzards

descended regularly to feed on the bloody Amerindian garbage. Hay’s

troop rode like Comanches and attacked like Comanches, with one exception:

Hays and his men were disciplined, purposeful as well as deadly. They

wasted no energy in exultation or victory dances, and no time making

ritual sport with captives. They could not be burdened with prisoners,

and they took none.

If possible, Hays preferred to surprise the Indians

and shoot them down in their sleeping robes, or else surprise a camp

and chase its warriors, dismounted, into brush. The Comanche warrior

was at a tremendous physical and psychological disadvantage when afoot,

and his lances and bows were ineffective in the brushy canyons in

which the Pehnahterkuh, the Honey-Eaters, liked to camp. Hay’s

men mauled the Pehnahterkuh from the Nueces to the Llano, killing

Amerindians of every age and both sexes. By their own lights, defending

a battered, bleeding, ravished frontier, they were not making war

but exterminating dangerous beasts.

Very little mention was made of this, but no one in

Texas would have had it any other way. The Lipan chief, Flacco, was

in awe of Hays, saying often that he was not afraid to ride into hell

all by himself. Lamar’s papers, in an age when few systematic

records were kept and every Texas political figure was inordinately

jealous, indicate that Hay’s troop was instrumental in halting

Comanche depredations on the southwestern frontier in 1840. Even Sam

Houston who deplored wars against the red men and was disgusted with

the brawling Texas borderlands, wrote, “You may depend on the

gallant Hays and his companions.” Hays’s bloody marauding

beyond the frontier was a great factor in the Comanches’ decision

to seek a truce. Other Ranger companies, formalized by the Texan Congress

as border troops, followed his example. The Pehnahterkuh were in no

sense exhausted or defeated, but the warfare against the tejanos was

ceasing to be sport. The Rangers sometimes wiped out camps whose warriors

were away raiding deep in Mexico. Also the Comanches quickly overcame

their initial superstitious fear of repeating pistols. The People

were not given to awe or cringing, and their chiefs quickly understood

that these were only guns of a new and better kind. They desired a

truce so that they might obtain such firearms from traders.

The above story is from the book, Comanches, The Destruction

of a People, by T.R. Fehrenbach.

The following story and picture is from the book, Encyclopedia of Indian Wars, by Gregory F. Michno.

Truckee River

3-4 June 1860, Wadsworth, Nevada: After their fight at Williams Station, John C. Hays and the Washoe Regiment marched north. Capt. Joseph Stewart and his regulars joined them at a campsite on the Truckee River. The next day the combined force moved eight miles down the river and built an earthwork defense. Downriver, in the valley near Pyramid Lake, an advance party found the remains of volunteers from the 12 May rout there. They also spotted 300 Paiute warriors rapidly approaching.

With the Paiutes in pursuit, the vanguard hurried back to the main force. The men formed a skirmish line about a mile long and held the Paiutes back, but they could not drive them from the field. After three hours, at sunset, the Paiutes pulled back north toward the lake. Stewart, Hays, and their men followed for a while, then built a fortification in which to spend the night.

The next morning, the force continued its pursuit, leaving one company in camp to care for the wounded. In a canyon, Paiutes ambushed the five advance riders, killing volunteer William Allen, the expedition's last fatality. After that, the Paiutes vanished; the command reached the south end of Pyramid Lake to find the village gone. After several days, Hays returned to Carson City and disbanded his regiment. Stewart stayed in the area for another month, but the Paiutes did not return.

In all, the regulars and volunteers killed 25 Paiutes and wounded about 20. The Paiutes killed 3 men and wounded 5.

|