|

||||

|

|

||||

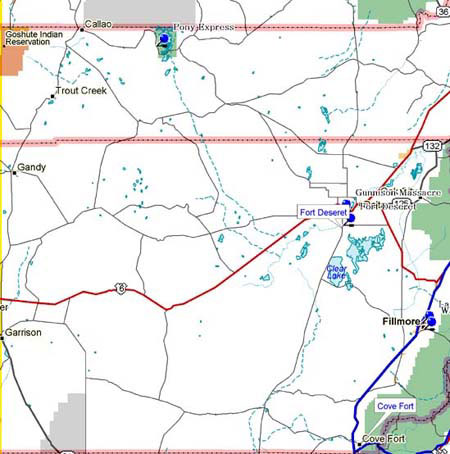

Fort DeseretMarker Topic: Fort Deseret Gunnison MassacreMarker Topic: Gunnison Massacre Bishop Call warned him of Indians near the Sevier River because an old Indian brave in the Kanosh Tribe had been killed by members of a California-bound wagon train. Moshoquop, son of the dead brave, had vowed to avenge his father. Gunnison knew Kanosh and Moshoquop as friends, but they did not know of his return to Utah. On the evening of October 28, 1853, Gunnison and his party made camp on the bank of the river. They took a few shots at migrating wildfowl. Two Indians heard the shots and crept near enough to see the military uniforms and army equipment, but no close enough to recognize the men. The Indians reported the news, and during the night plans were made and the camp was surrounded. At daylight the cook made a fire, Gunnison went to the river to wash up, and men began working with the horses. As the sun appeared over the mountain the first shot was fired. Three men escaped on horses, although one fell and had to hide in the brush. One man swam the river and hid in the willows. Eight men were killed by guns and arrows. The survivors made their way to Fillmore and reported the tragedy. Gunnison’s body was taken to Fillmore for burial. William Potter, a Mormon guide, was buried at his home in Manti. Six men rest in a common grave at this site. Pony ExpressMarker Topic: Boyd Springs Pony Express Station Here He Comes The Pony Express April 6, 1860-October 1861 Completion of the transcontinental telegraph line in 1861 put an end to the Pony Express. The “Talking Wire met the need for urgent communications and the overland stage served for general letters. Despite its high prices (up to $5 an ounce at its peak) the Pony Express was a losing enterprise from its beginning. Receipts were often high, but expenses were enormous. In spite of its contributions to the Union and the westward expansion, the Pony never received any financial assistance from the government. Yet its founders, William H. Russell, Alexander Majors, and William B. Waddell, felt the need was important, and the Pony Express operated in the red until it went out of business on October 28, 1861, four days after the first coast to coast telegraph message. Pony Express relay stations were from 10 to 35 miles apart along the route and each had 2 to 4 men and extra horses. About 500 of the heartiest western horses were bought at prices up to $200 each. There were about 80 riders in all and they were recruited from the most daring, determined, and toughest “wirey young fellows” in the west. Lightly equipped and armed with a Navy Colt revolver, each man rode at least 35 miles in each direction, changing horses at three relay stations along the way. Over his saddle the rider carried the mochila, a leather cover with four mail pouches for letters. He wasted no time at the relay stations, stopping only for water and to transfer the precious mochila onto a waiting horse. Day and night, good weather and bad, winter and summer, the Pony riders covered 10 to 15 miles an hour on their routes. Surprisingly, over the 18 months the Pony operated, only one mail pouch was lost. Service was held up for only one month during the Indian wars. Historic sites like these along the Pony Express route have been interpreted for your enjoyment as part of the nation’s bicentennial observance of the American Revolution. To aid in following the Pony Express route, concrete and wooden posts mark the actual trail. Station LifeKnown as Butte or Desert Station in the days of the Pony Express, this Pony Station gets its present name from Bit Boyd, a station keeper who continued to live here in the early years of this century. Life at the station was isolated and lonely. The daily routine of the station keeper, spare rider and blacksmith centered on caring for the horses and almost immediate departure of 2 riders each day. Living conditions were extremely crude. |

||||

|

||||