Southeast Texas |

Uncommemorated Historical Sites  (Blue Pinpoints with Black Numbers)

(Blue Pinpoints with Black Numbers)

Listed Alphabetically

62-Alexander, Amos R. | 84-Arreolo, Lieutenant Leandro | 52-Battle on the Rio Blanco | 70-Bastrop Indian Attack | 2-Brown's Fort | 61-Buckner's Rangers | 10-Camp Austin | 47-Camp Bee | 35-Camp Bowie | 9-Camp Cazneau | 7-Camp Chambers | 34-Camp Chambers | 27-Camp Corpus Christi | 36-Camp Crockett | 49-Camp Crockett | 45-Camp d' Asile | 16-Camp Felder | 19-Camp Groce | 32-Camp Irwin | 37-Camp Johnson | 28-Camp Marcy | 18-Camp Millican | 29-Camp Nueces | 46-Camp on the San Jacinto | 31-Camp Semmes | 17-Camp Waul | 55-Captain's Jesse Burnman and Amos Rawls | 51-Castleman's Cabin Massacre | 89-Clapp's Blockhouse | 85-Coleman Fort's Remuda, Indians Steal | 80-Colorado Depredations-Story One | 81-Colorado Depredations-Story Two | 50-Cooke's Camp | 88-Coryell, Slaying of Ranger James | 5-Dunn's Fort | 73-Duty, Matthew | 74-Edwards, John | 78-Elm Creek Fight, Sergeant Erath's | 60-Flowers and Cavina | 44-Fort Chambers | 11-Fort Colorado | 38-Fort Crockett | 40-Fort de Bolivar | 33-Fort Esperanza | 42-Fort Grigsby | 3-Fort Henderson | 41-Fort Las Casas | 43-Fort Sabine | 6-Fort Sullivan/Fort Nashville | 8-Fort Tumlinson | 14-Fort Wilbarger | 69-Greatest Fight | 76-Harris, Blakely and Another | 68-Hibbons Story | 56-Jones, Captain Randall | 71-Little River Settlers Attack | 39-Maison Rouge | 75-Menefee and Marlin | 30-Mission Nuestra Senora del Refugio | 13-Mission San Francisco Xavier Los Horcasitas | 48-Mission Senora de la Purisima Concepcion de Acuna | 15-Moore's Fort | 86-Post Oak Springs Massacre-1 | 87-Post Oak Springs Massacre-2 | 12-Presidio San Marcos de Neve | 77-Reed, Joseph and Braman | 67-Riley Massacre | 72-Rohrer, Conrad | 58-Ross, James J. | 65-San Gabriel, Depredation on the | 83-Seguin's Cavalry | 66-Taylor, Joseph | 59-Thompson, Thomas | 90-Trinity River Fort | 53-Tumlinson, John Jackson | 54-Tumlinson, Jr., and his brother Joseph, John Jackson | 82-Wren's Ambush, Lieutenant | 57-Wrightman, John

Historical Markers (Numbered in Red)

60- Alamo | 2-Battle of Jones Creek | 64-Battle of Brushy Creek | 76-Battle of Palo Alto | 17-Battle of Plum Creek | 70-Battle of Plum Creek | 77-Battle of Resaca de la Palma | 72-Battle of the Salado | 32-Battleground Prairie | 65-Battleground Prairie | 20-Bird Creek Battlefield | 69-Bird Creek Battlefield | 21-Bird Creek Indian Battle | 68-Bird Creek Indian Battle | 36-Black's Fort | 50-Camp Independence | 48-Camp Henry E. McCulloch | 88-Clapp, Captain Elisha | 38-Camp Mabry | 75-Carricitos (Thornton Skirmish) | 73-Dawson Massacre | 44-DeWitt's Fort | 1-Edens-Madden Massacre | 66-Manuel Flores | 7-Fort Anahuac | 8-Fort Anahuac | 10-Fort Bend | Fort Bend Museum | 15-Fort Boggy | 16-Fort Boggy, Site of | 23-Fort Casa Blanca, C. S. A. | 19-Fort Gates | 26-Fort Lipantitlan | 71-Fort Lipantitlan | 27-Fort Lipantitlan, On This Site Stood | 25-Fort Merrill, Site of | 35-Fort Milam | 33-Fort Oldham | 89-Fort Parker | 90-Fort Parker Memorial Park | 91-Old Fort Parker State Historic Site | 52-Old Quintana | 62-Fort Sam Houston Museum | 12-Fort St. Louis | 5-Fort Sullivan | 34-Fort Tenoxtitlan | 3-Fort Teran, Site of | 4-Fort Teran Park | 11-Fort Travis | 53-Fort Velasco | 45-Fort Waul | 51-Fort West Bernard Station | 85-Gotier Trace | 84-Harvey Massacre | 79-Hynes Bay | 30 & 63-Indian Battlefield | 22-Kenney's Fort | 18-Linnville, Site of the Town of | 31-Little River Fort | 86-McLean Claim, Daniel | 87-McLean-Sheridan-Barnes Slayings | 42-Mission de las Cabras | 56-Mission Nuestra Senora de la Luz | 6-Mission Nuestra Senora de la Luz del Orcoquisac and Presidio San Agustin de Ahumada | 46-Mission Nuestra Senora del Espiritu Santo de Zuniga | 47-Mission Nuestra Senora del Rosario | 57-Mission San Francisco de la Espada | 39-Mission San Ildefonso | 59-Mission San Jose | 58-Mission San Juan Capistrano | 13-Presidio de Nuestra Senora de Loreta de la Bahia | 43-Presidio El Fuerte de Santa Cruz del Cibolo | 14-Presidio La Bahia | 67-Rice, James O. | 49-Round Top House | 61-San Fernando Cathedral | 24-Stringfield Massacre | 78-Texas Rangers' Battle, Vicinity of | 9-Texas Revolution, Events at Anahuac Leading to the | 41-Washington-on-the-Brazos | 28-Webster Massacre | 29-Webster Massacre, Victims of the | 40-Wood's Fort

To South Texas Map

Pinpoint Information

Pinpoint Information

2-Brown's Fort

Possibly the earliest settlement fort in Texas, built around 1833 in northeastern Houston County by Reuben Brown.

3-Fort Henderson

This Texas Ranger fort was built by Major William H. Smith's battalion early in 1837 and commanded by Captain Lee C. Smith as part of the defensive line established by the Republic of Texas against marauding Plains Indians. The fort was named for General James Pinckney Henderson. It was on the upper Navasota River near the present boundaries of Robertson and Leon counties. At that time, this area was deep in Indian country. The fort was difficult to supply and of questionable defensive use. For those reasons the fort was abandoned soon after its construction, probably in the fall of 1837. There are no visible ruins.

5-Dunn's Fort

Dunn's Fort was established southwest of Wheelock in 1832. It was a combination land office-courthouse, but it was initially built for defense. A state commemorative marker is at the original site southwest of Wheelock close to the Robertson-Brazos county border.

6-Fort Sullivan and Fort Nashville

In the vicinity of where Highways 79 and 190 and FM 485 cross the Brazos were the now ghost towns Nashville (it had a fort) and Fort (Port) Sullivan. Both have disappeared, leaving an interesting history. As early as 1843, the settlements' developers dreamed of establishing Fort Sullivan as a part for steamboats moving up the Brazos River, and by 1845, a steamboat was driven up to the mouth of nearby Little River. In nearby Nashville, there were more than 20 stores and a population of 1,000. Then both of the communities vanished without a trace.

7-Camp Chambers

A regular army post near the site of present-day Marlin in Falls County, Fort Chambers was established in May or June of 1840 on the east bank of the Brazos River, two miles north of the present-day Highway 7 crossing. Nothing remains.

8-Fort Tumlinson

In 1836, Captain John Jackson Tumlinson, Jr., of the Rangers charged with patrolling and protecting the new Anglo settlements along the Colorado River north of Austin, built this fort on Brushy Creek in present-day Williamson County. There is a state historical marker on Highway 183 near present-day Leander noting the location of Fort Tumlinson.

9-Camp Cazneau

Located adjacent to Kenny Fort, east of present-day Round Rock, Camp Cazneau was on Brushy Creek at the Double File Trail Crossing created by Indians passing through the area. It was used in 1840 by the Travis Guards and Rifles under the command of George W. Bonnell when he led raids against the Comanches in May and June of that year.

10-Camp Austin

In 1846, during the Mexican War, a detachment of the 2nd Dragoons of the U.S. Army was moved from Indian Territory to Austin. Their camp, like many other holding camps at the time had no name. Two years later, the camp was named Camp Austin and was more involved with paperwork than patrols. When the Civil War broke out, the camps arsenal manufactured cannons and cartridges. Following the Civil War, 26 regiments of Federal infantry and cavalry were stationed here to restore order in Texas. Camp Austin at this time consisted mostly of tents with a mess hall, kitchen, bakery, and quarters. In August of 1875, the camp's garrison was closed and troops were moved to the frontier.

11-Fort Colorado

Fort or Camp Coleman, also Fort Colorado

After Texas gained its independence, Sam Houston authorized the formation of Texas Rangers and the establishment of blockhouses to protect settlers from Indian attacks. Two facilities were near Austin in 1836. The Texas Rangers established Camp Coleman, or Fort Colorado, as it would later be called. It was on high ground above the north bank of the Colorado River just west of Walnut Creek and six miles southeast of Austin in present-day Travis County. Built during 1836 by Colonel Robert M. Coleman, it was first garrisoned by two companies of his battalion. Lieutenant William H. Moore was the last commander of the fort when it was abandoned in April 1838. There are no remains of the blockhouse, abandoned as the frontier moved westward.

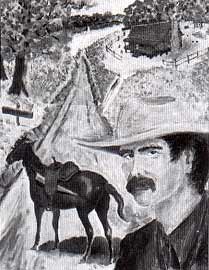

Colonel Robert Morris Coleman

Photo from DeShield's book, Border Wars of Texas.

Coleman wrote to Senator Sterling Robertson on October 16, describing Fort Colorado and the deployment of his new ranger battalion.

I have selected the most beautiful site I ever saw for the purpose. It is immediately under the foot of the mountains. The eminence is never the less commanding, and in every way suited to the object in view.

I have ordered Capt. Batton to build a block house at or near Milam, where he will station one half of his company. The other half of the company under the 1st Lieut. is also ordered to build a block house at, or near, the three forks of the Little River. I shall in a short time commence a block house at the head of San Marcos, and one at the crossing of the Guadalupe, by which means I hope to be able to give protection to the whole frontier west of the Brazos.

12-Presidio San Marcos de Neve

Presidio San Marcos de Neve was founded in the early nineteenth century four miles below present-day San Marcos, where the Old San Antonio Road crossed the San Marcos River. A flood in June of 1808 nearly wiped out the community. The colony held on for several years, but harassment by Comanche and Tonkawa Indians forced settlers to abandon it in 1812. Archeologists recently have discovered ruins, which are probably of the presidio and community. The location of these ruins is still being kept a secret.

13-Mission San Francisco Xavier Los Horcasitas

This was the first of three San Xavier missions, located on the San Gabriel River (then known as the San Xavier River) about five miles from present-day Rockdale. The beginning for the mission came in June 1745 when a group of Indians came to San Antonio asking for a mission to be built in their territory. During the winter of 1745 a temporary mission, known as Nuestra Senora de Los Dolores Del Rio de San Xavier, was built. Later in 1748, a permanent mission was established on the south bank to serve those tribes. Archeologists working in an area near the original site of the mission found indications of walls and burials, Spanish ceramics and glass, and Indian pottery and projectile points.

14-Fort Wilbarger

Josiah had joined Stephen F. Austin's colony in 1828 and received a Mexican land grant in present-day Bastrop County where he settled in the community of Utley near the Colorado River. The Wilbarger's home consisted of a cabin and a stockade that may have been a family fort. He also prepared a cave in the banks of the Colorado River for shelter in case of Indian attack. Little else is known about the fort. At one time there was a commemorative marker at the site of Wilbarger Bend in the Colorado. If the marker still exists, it is now on private property.

15-Moore's Fort

Colonel John Henry Moore

Photo from University of Texas at Austin, Prints and Photographs Collection,

The Center for American History, CN Number 03821

In 1826, John Henry Moore built two blockhouses within what are now the city limits of La Grange. Area settlers were also allowed to use this shelter as a defense against the Indians. Buildings from Moore's Fort have been rebuilt in the nearby community of Round Top.

16-Camp Felder

Camp Felder was a Confederate camp for Union prisoners of war. It was located near present-day Chappell Hill in Washington County and was named for Gabriel Felder, owner of the Brazos River bottomland where the camp was established.

17-Camp Waul

Camp Waul was a Confederate training camp seven miles north of Brenham and was named for Thomas Neville Waul. Waul's Texas Legion was organized on May 13, 1862 and ordered out of state in August that year.

18-Camp Millican

Texas' northern most terminal of the Houston and Texas Central Railroad was the settlement of Millican. It became the site of Camp Millican during the Civil War. Enlistees arrived by train to this camp that was nothing more than a gathering site. Sometimes recruits were trained here before marching for duty in Arkansas and Louisiana but some went to nearby camps to train. A marker for Camp Millican is across from the Millican Post Office on Highway 159.

19-Camp Groce

Colonel Leonard W. Groce's Liendo plantation stood on Clear Creek two miles east of present-day Hempstead in Waller County. Camp Groce, or Camp Liendo as it was frequently referred to, was probably established in 1862 to house Union soldiers captured by Confederate forces at the Battle of Galveston. Camp Groce served as a recruiting station for the Confederate Army and a refugee center for women and children fleeing southern states. In December of 1864, all of the prisoners at Camp Groce were paroled and the camp was permanently abandoned as a military prison as nearly 500 prisoners were taken to the port of Galveston where they were turned over to Union forces.

27-Camp Corpus Christi

In November of 1850, Camp Corpus Christi was established in Corpus Christi for two companies of the Fifth Infantry. The camp was moved the following April, when Commander Major G.R. Paul moved his troops 30 miles inland to a location that was also given the name Camp Corpus Christi. Regardless of a lack of good drinking water and there not being any permanent building materials, the camp stayed at this location for four years. Two companies of the Seventh Infantry manned Camp Corpus Christi and in 1852 it became the headquarters for General Persifor F. Smith until he moved his headquarters to San Antonio in 1855. There are no remains of Camp Corpus Christi.

28-Camp Marcy

General Zachary Taylor and his troops landed off San Jose Island near Aransas Pass on July 25, 1845 and there planted a U. S. flag on Texas soil for the first time. While waiting for the entire company of troops to land, Taylor selected a site for an encampment on a strip of the coast north of a settlement called Kenney's Ranch. The camp was strongly fortified with a surrounding wall that had slots cut for rifle firing and two cannons mounted for defense. The camp was called Camp Marcy. Artesian Park in Corpus Christi has a monument and marker to honor Zachary Taylor, otherwise there is no way to know that 3,000 troops once camped in what is now downtown.

29-Camp Nueces

Camp Nueces was established in 1842 in the Corpus Christi Bay area near another camp called Kenney's Fort. The two camps as well as nearby Camps Williams and Everitt were probably built in response to a fear in the 1830-40s that Mexico might invade Texas by the sea.

30-Mission Nuestra Senora del Refugio

This was the last mission the Spanish established in Texas. Founded February 4, 1793, it was part of a plan by Spanish priests to convert all the Indian tribes living along the Texas coast. Indians helped choose the mission site in an area known as El Paraje del Refugio "Place of Refuge." This new mission was named Nuestra Senora del Refugio. In January 1795, the mission moved to its final location at the site of present-day town of Refugio. Despite difficulties, the construction of the mission was nearly completed by 1799. Traces of the ruins of the mission are found under the structure of Our Lady of Refuge Catholic Church in Refugio.

31-Camp Semmes

Camp Semmes was built on San Jose Island in the Gulf of Mexico in Aransas County as a Confederate post for storing cotton. It was captured by the Union forces in 1863 and then recaptured by the Confederacy. It was then retaken once again as the Union fought to gain control of the cotton grown in Texas. These continuing fights destroyed the only town on the island, Aransas, and it was never rebuilt.

32-Camp Irwin

Twelve miles inland from Port Lavaca, the Second Illinois Volunteers of Brigadier-General John E. Wool established Camp Irwin on August 1, 1846, as a holding camp until their supplies arrived. Nothing remains of Camp Irwin, except a place in history.

33-Fort Esperanza (Also known as Fort De Bray and Fort Washington)

This fort was a Civil War earthwork fortification on the east shore of Matagorda Island constructed to guard Cavallo Pass, the entry to Matagorda Bay. It was built in 1861 when it was determined that Fort Washington, a small fort near the lighthouse on Matagorda Island was too exposed. On November 29th, 1863, the Confederates, outnumbered and outflanked, evacuated the fort and it was occupied and repaired by Union forces and they used it as a base of operations for other campaigns in the area. In the spring of 1864, Union troops withdrew from Matagorda Bay and the fort was then reoccupied by the Confederates and held until the end of the war. Eastern walls of the fort were destroyed as the shoreline was eroded by a storm in 1868. By 1878, the rest of the 9-foot-high, 20-foot-thick, turf-covered walls had eroded away. Outlying emplacements and rifle pits can still be traced in some areas. Nothing else remains.

34-Camp Chambers

This was the last camp established along the Lavaca and Navidad rivers by the army of the Republic of Texas. It was occupied from August through October in 1837 under command of Colonel Edwin Morehouse, and was named for Major-General Thomas Jefferson Chambers. The camp was located on Arenosa Creek near the road from Texana to Victoria.

35-Camp Bowie

The principal encampment of the army of the Republic of Texas from April 22 through the middle of June 1837, was Camp Bowie located on the east side of the Navidad River at Red Bluff, 8 miles southeast of the community of Edna. Nothing remains of this camp.

36-Camp Crockett

Named for Alamo defender David Crockett, the camp became the main encampment and headquarters of the army of the Republic of Texas after Camp Bowie was closed in June 1837. Camp Crockett was somewhere in central Jackson County, probably on the Navidad River near Camp Bowie and northeast of the site of present-day Edna. Colonel H.R.A. Wiggington commanded the camp until it was abandoned in July. The troops were then transferred to Camp Chambers.

37-Camp Johnson

One of the many camps established in counties along the Gulf coast during the Texas Revolution, Camp Johnson was the headquarters for the Texans army around September 1836. The camp was probably named for Francis W. Johnson who had fought at the Siege of Bexar in 1835. It was located near the Lavaca River five miles from the Dimmit Landing and four miles south-southeast of present-day Vanderbilt.

38-Fort Crockett

Fort Crockett was first established in Galveston around 1834. It was rebuilt in 1897 in the vicinity of present-day 45th Street at Seawall Boulevard. It was not manned until 1898, then destroyed by the hurricane of 1900. A new Fort Crockett was subsequently built in the twentieth century for a training facility for artillerymen. The buildings are being used by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Texas A&M University and also Galveston College.

39-Maison Rouge (The Red House)

Maison Rouge, at the present-day site of Saint Mary's Infirmary, was a block long and was armed with 36-pound cannons inside and a battery of 42-pounders outside. Pirates Jean and Pierre Laffite considered Maison Rouge their fortress. Maison Rouge was destroyed by one of the hurricanes that ripped Galveston in the 1800s.

40-Fort de Bolivar

Serving as a rendezvous place for Indians, pirates, freebooters, privateers, filibusters, explorers, and settlers, the peninsula of Point Bolivar found its place in the history of Texas. Francisco Xavier Mina built an earthwork fortification there in 1816 and after Mina's defeat by Mexico, the French pirate, Pierre Laffite recruited Mina's troops. Pierre made a base, Fort de Bolivar, on the peninsula. There is evidence that both Laffite brothers may have been in conspiracy with French settlers at Champ d' Asile in what was later revealed to be a Napoleonic plot to invade Mexico. Confederate troops destroyed the Point Bolivar lighthouse to avoid assisting the enemy.

41-Fort Las Casas

In 1818, Dr. James Long came to Texas with 300 troops to liberate the land. In 1819, he established his headquarters, Fort Las Casas, on the bay side of Bolivar Peninsula at the present site of Fort Travis. Las Casas was made of the only material available; mud and sticks.

42-Fort Grigsby

Fort Grigsby was located at the site of present-day Port Neches, southeast of Beaumont, as part of the defense to block any Union advance after the fall of Fort Sabine. It was occupied from October to December in 1862, then was no longer necessary after the construction of Fort Manhassett. Fort Grigsby seems to have been abandoned after July 1863.

43-Fort Sabine

Citizens of Sabine Pass in the southeast corner of the state, fearing a Union invasion during the Civil War, built a fort to protect their town. Residents, including slaves, constructed a dirt and timber earthworks fort overlooking the Sabine River. September 24, 1862, the fort was shelled by Union gunboats and severely damaged. Following construction of a new fort (Griffin) the 32-pounds cannons were then moved and installed there.

44-Fort Chambers

This was a mud fortification built during the Civil War by the Confederacy in late 1862. It was located halfway between the site of Fort Anahuac and the town of Anahuac in Chambers County. The small fort included two cannons, a 24-pounder and a 32-pounder, that were later mounted outside the doors of Galveston's Artillery Hall. Nothing else remains.

45-Camp d'Asile

Frenchmen arrived in Galveston in 1818, led by French General Charles Lallemand, whom the British refused to accompany Napoleon into exile. The group claimed to be exiles from France and only wanted to settle in Texas and establish a new life. They built their fortification along the Trinity River near the Liberty-to-Nacogdoches Trail. One source reports the camp was in the vicinity of Moss Bluff, north of Wallisville, in Liberty County. While another source, a book published in Paris in 1819, says the location was near Liberty. A third source reports there were two forts built (at undisclosed locations) along the river. The 1819 Paris book reported that the settlement had more than 400 persons, including Germans and Spaniards, and contained four forts with eight artillery pieces. Another report describes it as being a five-sided fort containing twenty-eight wooded houses, each a miniature fort in itself. Despite these reports of its large size, archeologists today have found no ruins or artifacts.

46-Camp on the San Jacinto

San Jacinto Battleground State Historical Park, the site of the Battle of San Jacinto, is located along the San Jacinto River off of I-10 east of Houston. This is the battle where Sam Houston reminded his men of the fall of Goliad and the Alamo. As the battle began and the forces ran forward, they cried, "Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!"

47-Camp Bee

The Second Texas Infantry, a Confederate regiment organized in Galveston in 1861, was moved to Camp Bee in the Houston area for training. Little is known of Camp Bee. It remained in existence only until after the war. There is no history of the camp after that era.

48-Mission Senora de la Purisima Concepcion de Acuna

Mission Concepcion was first established as Mission Senora de la Purisima Concepcion de Los Hainai in East Texas in 1716. It was moved to its present site near San Antonio in 1731 after Spain and France went to war. Missionaries had the Indians build homes inside the walls, and tried to replace the traditional Indians rituals with Christian beliefs. Initial success was quickly overcome when other Indians raided. Indians attacks continued into the 19th century. Later, during the times before the Texas Revolution, this mission was a frequent meeting place for revolutionaries and it was the scene of a battle in the Siege of Bexar in 1835. During the Mexican War, Mission Concepcion was used as a barracks for Federal troops. Concepcion is well preserved and located on Missions Trail in San Antonio. Its church has never fallen into ruin and it is considered to be the oldest un-restored mission in the U.S.

49-Camp Crockett

Located on a spring three miles north of the Alamo, this camp was home to the troops of General John E. Wool in the Mexican War. San Pedro Park in San Antonio is now where Camp Crockett once stood.

50-Cooke's Camp (Not Shown on Map) Further West

Named for founder William Gordon Cooke who arrived in Texas in October, 1835, with a volunteer company called the New Orleans Greys. Headquarters camp established in San Antonio. Exemplary service during the Battle for Independence and later served as a colonel of the infantry and laid out the road from Little River to the Red River in 1840. Took every opportunity to fight Mexico including Somervell, Snively and Edwin Moore's expedition to the Yucatan. Cooke County is also named for him.

51-Massacre at Castleman's Cabin

15 mi. W of Gonzales April 15th, 1835. From the book, Savage Frontier, by Stephen L. Moore:

The campground was ominously quiet as the first rays of sunlight filtered through the trees along Sandies Creek. The dawn air was cool on the mid-April morning in South Texas. The tranquility was violently interrupted by the sudden report of rifles and resounding war whoops as more than sixty Comanche Indians descended on the scene.

The men of the camp scrambled to make a stand. Improvising breastworks of carts, packsaddles, and trading goods, the besieged fired back at the howling Indians who outnumbered them by upwards of six to one. The contest was fierce, but it was over before it had begun.

From a small porthole type window in his pioneer cabin several hundred yards away, John Castleman could only watch the massacre in anguish. He was frustrated that he could not assist the besieged and that they had not heeded his advice.

His gut instinct was to open fire with his rifle, however futile the effort may prove to be. Only the pleading of Castleman's wife restrained him. The first shot he fired would only ensure that he, his wife, and his children would also be slaughtered. Even still, it was difficult to watch as others died before him.

Castleman and his pioneer family had become bystanders to a bloody Indian depredation in south central Texas. It was April 1835 when the Indians descended near his place and slaughtered a party of traders.

John Castleman, a backwoodsman from Missouri, had settled with his wife, four children, and his wife's mother in the autumn of 1833 fifteen miles west of Gonzales. His cabin often served as a place of refuge for travelers moving down the San Antonio Road from Gonzales. Castleman's place was located in present Gonzales on Sandies Creek, a good watering hole. Indians were known to be about the area, and they had even killed his four dogs in one attempt to steal Castleman's horses.

...The traders declined the offer to use Castleman's cabin, choosing to retire for the night near the waterhole. The Indians attacked these traders right at daylight, the yelling from which had awakened Castleman. The traders fired back and continued to hold their ground for some four hours while the Indians circled them. The attackers slowly tightened their circle as the morning sun rose, falling back temporarily whenever the traders managed to inflict damage on their own numbers.

The traders suffered losses and drew to a desperate point. The furious Comanches finally took advantage of their enemies' desperation and made an all-out onslaught from three sides. They succeeded in drawing the fire of the party simultaneously and left them momentarily unloaded. During this brief instant, the Indians rushed in with victorious war whoops and fell upon the traders in hand-to-hand combat.

Raiding to acquire fine stock and other goods became a ruthless sport to the Comanche (translatable as "the real people" in Indian tongue) as settlement of Texas began to encroach upon the hunting lands the Indians had long claimed. By 1830 the Indian population in the territory of Texas was perhaps fifteen thousand compared to about seventeen thousand settlers of Anglo-European, Mexican national, and black origin. In combat with early settlers, the Comanche warriors had learned to exploit any advantage a battle might offer them, such as lengthy time required to reload weapons in the case of the French and Mexican traders. The determined Indians could accurately fire a half dozen arrows in the time it took an opponent to reload his rifle a single time. The battlewise Comanches forced the traders to discharge all their weapons at once before moving in to slaughter the men before they could reload.

This last terrific charge was witnessed by Castleman from his window, and he immediately realized that it was all over for the poor traders. The victims were brutally mutilated and scalped. The Comanches stayed long enough to dispose of their own dead, round up the traders' mules, and collect all of the booty that was desired. As they slowly rode past his house single file, Castleman counted eighty surviving warriors, each shaking his shield or lance at the house as they passed.

52-Battle on the Rio Blanco

Castleman gathered his family and hurried to Gonzales where volunteers were raised for pursuit. Just outside of San Marcos on bluff of Blanco River, April 18th, 1835, Captain Bartlett D. McClure's posse of about thirty men found the murderers. The posse split into two parties, one circling around while the other attacked. John Castleman was among those who killed a few warriors during the advance. Andrew Sowell Sr. was part of the group of volunteers waiting behind the Indians in ambush. His nephew, A.J. Sowell, later wrote:

Asa J.L. Sowell

Several shots were fired, and a third Indian had his bow stick shot in two while in the act of discharging an arrow. Andrew Sowell attempted to fire with a flintlock rifle, but it flashed in the pan. He had stopped up the touch-hole to keep the powder dry in the fog, and had forgotten to take it out. The other Indians now ran back towards the river, yelling loudly. By this time most of the men had gotten clear of the brush and charged with McClure across the open ground.

...Captain McClure's volunteer forces pursued the Indians to the Blanco River, where the fighting became more general. More of the fifty-odd Comanches were killed as they tried to cross the water with their stolen goods. Andrew Sowell shot and killed on Indian as he tried in vain to climb a steep bank on the far side. In the end, they left much of their spoils behind and moved swiftly from the area. The whites chose not to cross the river and continue their pursuit. They were fortunate to have not had any man killed or any serious injuries sustained.

53-65 are taken directly from the book, Savage Frontier, by Stephen L. Moore.

53-John Jackson Tumlinson

John Jackson Tumlinson, who had requested the need for a ranger-type system in January 1823, was killed on July 6, 1823, by a band of Indians near the present town of Seguin in the Colorado settlement. Tumlinson and a companion, aide Joseph Newman, had been en route to San Antonio to secure ammunition requested by Moses Morrison's men when he was killed by Karankawa and Huaco Indians.

54-John Jackson Tumlinson, Jr., and his brother Joseph

John Jackson Tumlinson's son, John Jackson Tumlinson Jr., later a respected ranger captain, collected a posse and led them against a band of thirteen Huaco (Waco) Indians who had camped above the present town of Columbus. The posse leader's teenage brother, Joseph Tumlinson, acted as a scout for this unit and managed to kill the first Indian when the Texans surprised the Waco camp. Captain Tumlinson's posse killed all but one of the Indians.

55-Captains Jesse Burnman and Amos Rawls

In June 1824 Austin reorganized his militia into five companies. Soon thereafter, Captains Jesse Burnam and Amos Rawls fought nine Karankawa Indians on the Colorado River, killing eight. Austin also sent Captain Aylett C. Buckner with a party of volunteers to the Waco Indian village to make a treaty with the Waco, Tawakoni, and Towash Indians.

56-Captain Randall Jones

Captain Randall Jones' twenty-three man militia company was authorized by Austin to make an expedition against a force of Indians who had killed several immigrants en route to Austin's Colony. Jones' men fought two skirmishes with the Indians in September 1824. In the first, the whites killed or drove away all of their attackers. On the following day, Captain Jones and his men made a surprise dawn attack on the Indians. They managed to kill an estimated fifteen Indians before losing three of their own killed and several wounded, forcing Jones to order a retreat.

57-John Wightman

One of the little settlements that would remain a centerpiece for Indian troubles and revolution was Gonzales, the capital of Green DeWitt's young Texas colony. The area of DeWitt's Colony as contracted with the Mexican government included all of present Gonzales, Caldwell, Guadalupe, and DeWitt Counties and portions of Lavaca, Wilson, and Karnes Counties.

The peace in this area was shattered on July 2, 1826, when a party of Indians attacked a group of pioneers, stealing their horses and personal effects. Bazil Durbin was wounded by a rifle ball that drove so deeply into his shoulder that it remained there for the next thirty-two years of his life. The Indians next plundered the double log home of James Kerr, where John Wightman had been left alone in charge of the premises. Wightman was killed, mutilated, and had his scalp removed by the Indians. The fear spread by this depredation was enough to prevent the Gonzales area from being permanently settled again until the spring of 1828.

58-James J. Ross

The most serious encounter of 1826 occurred when Tawakoni Indians came into the settlements stealing horse and hunting the Tonkawa Indians they so hated. The Tonkawa name was derived from "They all stay together" but has been translated as "men who eat men." They were also reported to have killed and scalped a Mexican resident while on their depredation. The Indians made their camp in the bed of Ross Creek in present Fayette County near the town that later became La Grange. Captain James J. Ross led thirty-one militiamen out to fight these Indians on April 4, 1826. His party was composed of many future Fayette County settlers, including John J. Tumlinson Jr., John Cryer, and S. A. Anderson. When Ross's men raided the Indian camp, they caught them by surprise. Some of the Indians were dancing around with fresh scalps, while others were parching corn of lying down. Of an estimated sixteen Indians, the Texans killed eight and wounded most of the others.

59-Thomas Thompson

The balance of 1827 and 1828 found Austin Colony settlers and the native Indians on somewhat better relations. In July 1829, however, a battle was fought against Indians who had taken control of Thomas Thompson's small farm near present Bastrop on the Colorado River. Thompson led then men in a fight against the Indians, killing four and chasing away the others. Colonel Austin ordered two volunteer companies of fifty men raised. The companies were under Captains Oliver Jones and Bartlett Sims and under the supervision of Colonel Abner Kuykendall. Captain Harvey S. Brown raised another volunteer company during this time due to murders and depredations committed by Indians around the Gonzales area. Although Captain Sims and his company scouted extensively in pursuit of the Indians, these combined forces only managed to kill one Indian while on their offensive.

60-Flowers and Cavina

The homes of Charles Cavina, who had immigrated to Texas in 1828 and received a league in Matagorda County, and neighbor Elisha Flowers were attacked by an estimated seventy Karankawa Indians in 1830 near Live Oak Bayou on Old Caney Creek in Austin's Colony. Four women in the Cavina house were killed, as was Mrs. Flowers. Two badly wounded girls survived the assault.

61-Buckner's Rangers

Cavina raised sixty of Austin's settlers, and command was given to Captain Buckner. At the site of present Matagorda on the Colorado River, Buckner's men fought a heated battle with the raiding Indians. Among his volunteers who narrowly escaped death in this battle was Moses Morrison, who had been the organizer of what was arguably the earliest Texas Rangers. In the ensuing massacre, the vengeful Texans killed Indian men and women. As many as forty or fifty Indians were killed and the riverbanks literally ran red with blood.

62-Amos R. Alexander

From the Falls of the Brazos, the townspeople selected Samuel McFall to run ahead and warn the Bastrop citizens. Bastrop was the uppermost white settlement of any size on the Colorado River in 1835. The local residents had been forced to band together to protect themselves from neighboring Waco, Tawakoni, Kichai, and Comanche raids. Consequently, a strong log stockade or fort was erected in the center of the little town. In the event of a serious Indian attack, the townspeople could take shelter inside.

McFall, a lean and quick man of six feet, three inches, ran the distance on foot and is fabled to have been a faster runner than most saddle horses of the time. Before he could arrive, a party of eight Indians made a vicious attack on June 1. On the road from San Felipe to Bastrop, they attacked the wagon of Amos R. Alexander near Cummins Creek.

Alexander, a Pennsylvania native, had brought his wife and two sons to Texas in the spring of 1833. They settled in Bastrop and eventually opened a store and hotel. In April 1835 Amos and son Amos Jr. went to the coast to get a supply of goods they had ordered. They hired two other men to serve as teamsters to haul their goods. The Alexanders were attacked by Indians on June 1 at Pin Oak Creek about thirty-five miles from Bastrop.

Amos Alexander was killed outright. His son was on horseback and was shot through the body. The younger Alexander rode full speed from the scene of the attack toward Moore's Fort at La Grange, the last town they had passed. He met the second wagon being hauled by the two brothers his father had hired as teamsters. The three started for Moore's Fort, but the young Alexander died from his wounds. His body was laid under a tree and covered with leaves and moss. More

65-Depredation on the San Gabriel

During late September, surveyor Thomas A. Graves set out from Bastrop in Robertson's Colony with a party of seventeen land surveyors and speculators. After surveying ten leagues near the San Gabriel River, one of the small groups of surveyors was attacked by a party of Indians. An Irishman named Lang was killed and scalped while working his compass. One of the men of the party of four escaped and ran to the men under Graves to spread the news. The other two men being unaccounted for, the men under Graves decided to go in search of them.

One of Graves' surveyors was George Erath, who had joined his surveying party after serving in the Moore expedition through August 28. Erath felt that "there was little danger in our whole party remaining a few days longer," as the Indians were believed to have fled after lifting their scalps. Graves' men went to the scene of the attack but didn't find any bodies. The Indian attack was enough to cut short this surveying trip, as Erath recalled:

We paused there and, after another deliberation, Graves cut the matter short by declaring he had fitted out the expedition, would have to pay the hands, and did not propose to be at unnecessary expense in public service. So we turned back. Had we gone but a few hundred yards farther we would have found Lang's body.

Before returning to Bastrop, Graves' surveying party did find two other badly frightened survivors of this Indian depredation.

Graves, Erath, and the other surveyors returned from their expedition early in October and made town at Hornsby's settlement. There, they found events that would forever change the future of Texas had occurred in their absence.

The preceeding 53-65 are taken directly from the book, Savage Frontier, by Stephen L. Moore.

66-Joseph Taylor

Some three miles southeast of present day Belton, Kickapoo's attacked the home of Joseph Taylor on the night of November 12th, 1835.

"Heroic Defense of the Taylor Family" was originally

published in James DeShields' 1912 book, Border Wars of Texas.

The family held off the Indians and managed to kill two of the attackers. At one point the mother threw a shovel of hot coals into the face of an Indian who was peering through a hole in the wall. Two months after the fight, their fourteen year old son Stephen Frazier joined Sterling Robertson's Ranger company. Rangers arrived the day after the attack, including George Chapman, who lived at the Taylor's home and later married one of the Taylor daughters. She later recalled:

My late husband came to us at the home of Mr. Childers. He had been to our house. The bodies of the two Indians were being eaten by the hogs.

The Rangers cut the heads off of the dead warriors and stuck them on poles as a warning to any other hostiles that should pass that way.

67-Riley Massacre

January 1836, Thomas and James Riley were attacked by a band of forty Caddos and Comanches. Thomas was killed and his brother was severely wounded but survived. Stephen L. Moore describes in his book, Savage Frontier, how the Riley depredation caused the formation of Sterling Clack Robinson's Ranger company in January, 1836.

This event happened along the upper tributaries of the Little River, a hunting grounds the Indians called "Teha Lanna" or "the Land of Beauty." The pioneers they attacked were brothers James and Thomas Riley, who were traveling with two loaded wagons and their wives, children, and another young man.

Near the mouth of Brushy Creek on the San Gabriel River, the Rileys met surveyor William Crain Sparks and his servant Jack. These three were returning from Sparks' camp near the Little River, where they had encountered Indians. Sparks and Jack Had set out from Tenoxtitlan with a man named Michael Reed and an ox wagon loaded with corn. As dusk fell on their camp on the Little River, Reed crossed the river to visit the camp of newly arrived emigrant John Welsh. During his absence, Indians attacked the camp of Sparks and Jack, who both hid in a thicket.

Sparks and Jack survived then set out after morning for Tenoxtitlan. En route, near where Brushy Creek met the San Gabriel, these two happened upon the Rileys. They advised the Rileys to turn back, but their warning was not heeded. Within another mile the Rileys encountered a band of about forty Caddos and Comanches. The Indians claimed to be friendly and stated that they were only following Sparks and his black man.

The Riley party decided to turn back at this point, but the Indians attacked them just as they reached the Brushy Creek bottom. One of the Indians leaped onto the lead wagon horse and cut loose the harness. Before he could strike, one of the Riley men shot him dead and thus started the general fight. Thomas Riley managed to kill two Indians before being mortally wounded himself. James Riley also killed two of his attackers but was severely wounded in four places before the remaining Indians fled.

The younger man accompanying the Rileys fled with the women and children during the engagement. They reached the settlements on the Brazos safely within two days. The seriously wounded James Riley laid his brother Thomas's body on a mattress and wrapped it before mounting a horse and heading for Yellow Prairie in present Burleson County. After reaching safety the next day, he returned with a party to bury his brother.

Riley survived with severe wounds that kept him confined for a long period of time. A petition was presented to the Congress of Texas in 1840 for the republic to provide aid to the crippled James Riley in supporting his wife and six children.

Empresario Sterling Clack Robertson organized a ranger company to defend the citizens of his colony. The unit's muster roll shows that they were mustered into service on January 17, 1836. The Riley death was reported in the January 23 issue of the Telegraph and Texas Register, noting that the Indians had taken eight of the Riley's horses. The paper reported that a company of twenty-five men had gone immediately in pursuit of the Indians. This number obviously increased as more men joined Robertson's company, for his muster roll, signed by Robertson as "Captain Rangers," shows a total of sixty-five men.

Among the members of the company was Elijah Sterling Clack Robertson, the fifteen-year old son of the captain. The company also included rangers who had recently served under Captains Daniel Friar and Eli Seale. Friar's reduced company remained in service throughout January, although at least eight of his men had enlisted in Robertson's new company.

Robertson's company had returned back to town by January 26, on which date empresario Robertson was conducting colony business. It is unknown exactly how long Robertson's ranger company remained in service, but it was disbanded by late February. Sterling Robertson was elected to the Convention of March 1 on February 1. Correspondence of Captain Robertson further places him at Milam as of February 7 and at the Falls of the Brazos as of February 18.

68-Hibbons Story

January 20th, 1836. Ten miles northwest of Austin. The following story is from the book, The Texas Rangers, by Walter Prescott Webb:

The Rangers were an irregular body; they were mounted; they furnished their own horses and arms; they had no surgeon, no flag, none of the paraphernalia of the regular service. They were distinct from the regular army and also from the militia…

Major Robert McAlpin Williamson

The crutch (pictured above) was needed because he wore a wooden leg

thus the nickname Three-legged Willie. He previously commanded a Ranger

company in 1835 in Col. Moore's battalion. He liked to tell a story

about laying an ambush for some Indians that had been trailing his company

for days. He ordered an extra large camp fire built that evening and

had the men wrap their blankets around logs so it would appear the whole

company was asleep. The Indians attacked their prey with knives and

by the time they realized they were striking wooden logs, they were

wiped out by Ranger gunfire. Photo from the UT Institute of Texan Cultures of San Antonio, No. 70-497.

The officers of this ranging corps were elected on the night of November 28. The captains were Isaac W. Burton, William H. Arrington, and John J. Tumlinson. R.M. Williamson and James Kerr were nominated for the office of major. Williamson was elected. Noah Smithwick served under Tumlinson and R.M. Williamson, and has left us some account of what these Rangers did. Texas had an army of five or six hundred men, and was preparing to invade Mexico. The Indians took advantage of the situation and began to raid the frontier and murder the citizens. 'So,' says Smithwick, 'the government provided for their protection as best it could with the means at its disposal, graciously permitting the citizens to protect themselves by organizing and equipping ranging companies.'Since Smithwick's account gives such an excellent idea of the nature of the Rangers' work in this early period, it is given in his own words. Click on picture below for his account.

Noah Smithwick

Photo from the University of Texas at Austin, Prints and Photographs Collection,

Center for American History CN Number 01542.

69-The Greatest Fight

February 25th, 8-1/2 miles off of the mouth of Brushy Creek off the Brazos. There was a party of ten led by surveyor Thomas A. Graves that was attacked by more than one hundred Indians. Two were killed including James Drake and two others wounded.

Graves led his men in a retreat to their raft on the Little River. Bernard Holtzclaw narrowly escaped injury when a bullet passed through his pantaloons.

Two days after the attack, Graves wrote a letter to Sterling Robertson from the Little River:

I suppose from appearances there could not have been less than one hundred. I had pitched my tent cloth in the open post oak timber within eight miles and a half of the mouth of Brushy Creek and having made [no] particular discovery of Indian sign previously, we laid down carelessly as we had done before; and on Friday morning a little before daylight they charged up within twenty paces and discharged 15 or 18 guns and killed two of the company and wounded two others.

70-Bastrop Indian Attack

May 14th, 1836, a band of ten to fifteen Comanches carrying a white flag approached men working in the Hornsby's field. John Williams and Howell Haggard were speared and shot down. The other men took cover and the Indians eventually decided against another attack and departed with a hundred head of cattle from the neighborhood.

71-Little River Settlers Attack

Orville Thomas Tyler (1810-1886) was among the

Childers party that was attacked by Indians on June 4, 1836.

Photo from DeShield's book, Border Wars of Texas.

June 4th, 1836, Cameron Texas, seventeen settlers under Captain Goldsby Childers were retreating to Nashville for protection from the warring Indians. Montgomery Shackleford describes the account:

"When they approached within two hundred yards, they divided, one half to the right, the other half to the left-passed us shooting at us-and pursued and killed Crouch and Davidson, who were some three hundred yards ahead of us. Before they could gain, those of us who were near the wagon made our way to some timber that was near. The Indians drove off our cattle and took one horse; the balance of the company escaped without further injury."

The Indians scalped Crouch and Davidson after killing them and began to fight over who would keep the scalps and booty. Childers took this opportunity to lead his party to safety under the cover of some oak trees. The Indians turned back and headed for the Little River houses where they found the remaining families. Daniel Monroe relates:

"They used guns, bows and arrows, and spears. Whilst defending themselves in their house against the Indians, William Smith was shot on the outside of the door through the leg by a rifle ball. They shot and killed deponent's horse whilst tied to the house-killed many cattle-drove the balance off-and plundered a wagon."

A few days later, Judge O. T. Tyler performed last rites at the gravesite on the prairie where the killings took place.

Deadly Summer of 1836 72-77

72-74 are directly from the book, Savage Frontier,

by Stephen L. Moore.

72-Conrad Rohrer

On June 7 Indians plundered the house of Nathaniel Moore, and on the next day, June 8, attacked the house of Thomas Moore. Veteran ranger Conrad Rohrer was outside Moore's house at this moment attempting to saddle his horse. Rohrer had served Sam Houston's army as a special wagon master and had been among Captain John Tumlinson's early rangers during the revolution. He was shot down dead in the yard.

73-Matthew Duty

In another depredation, Bastrop area citizen Matthew Duty was killed while riding out alone one night to look over his crops. He had barely gotten out of sight of town when shots were heard. His horse returned on the run, its saddle splattered with blood. When an armed party rode out to look for Duty, he was found murdered and scalped.

74-John Edwards

Also during the summer of 1836, Indians killed Texas pioneer John Edwards, who had been traveling in company with Bartholomew Manlove from Bastrop to Washington. Manlove rode for his life, but the Indians killed Edwards. He was repeatedly speared and then scalped. The Indians took his horse and rifle.

75-Menefee and Marlin

Laban and Jarrett Menefee and John Marlin fought four Indians near the Colorado River. One Indian was killed and all three men claimed credit. They examined the body and found two bullet holes no more than two inches apart. They went a little further and were attacked by more Indians in which they managed to kill two. They chased the remainder into a timber thicket, killing one more in the process.

76-Harris, Blakely and Another

Also at this place, Harris, Blakely and another man came down the river to slaughter a cow when they were attacked in a ravine. Blakely escaped but Harris and the other man were shot and dismembered and their entrails were strewn around the bushes. They cut off their arms and removed their hearts, which were apparently eaten by the Indians.

77-Joseph and Braman Reed

Joseph was attacked by forty or more Indians, reaching his own house before he died. His wife drug him to safety before he could be mutilated or scalped. His brother attacked the camp with some volunteers and managed to kill the chief before being killed. The others in his party were wounded which may explain why they scalped the Indian.

78-Sergeant Erath's Elm Creek Fight

George Erath

Photo from DeShield's book, Border Wars of Texas.

January 7th, 1837, Sergeant Erath had ten horsebacked Rangers (all they had was ten horses). Erath's men could hear the Indians coughing. They crept up the river bank until they had a good view. Erath recalled that all were:

"dressed, a number of them with hats on, and busy breaking brush and gathering wood to make fires. We dodged back to the low ground, but advanced toward them, it not yet being broad daylight. Our sight of them revealed the fact that we had to deal with the formidable kind, about a hundred strong. There was not time to retire or consult. Everyone had been quite willing to acquiesce in my actions and orders up to this time. To apprehensions expressed I had answered that we were employed by the government to protect the citizens, and let the result of our attempt be what it might, the Indians would at least be interfered with and delayed from going farther down the country toward the settlements."

They took a position under the river bank twenty five yards from the camp and on command began firing. Within a few minutes, David Clark and Frank Childers fell dead. The remainder broke into two groups, one retreated while the other covered them with fire.

Colorado Depredations

80-Colorado Depredations-Story One

February 1837, a party of forty Comanches came into Fayette County taking horses and captives. They killed the Honorable John G. Robison and his brother, Walter. The next day, the judge's son, Joel, a veteran of San Jacinto and famous for having captured Santa Anna, heard of the raiding and went out looking for his father and uncle. He said:

"I had scarcely gone a mile, when, in the open post oak woods I found my father's cart and oxen standing in the road. The groceries were also in the cart. But neither father nor uncle were there. I had now no doubt of their fate. The conviction that they were murdered shot into my heart like a thunder bolt. Riding on a few yards further, I discovered buzzards collecting near the road. My approach scared them away and revealed to my sight the body of my father, nude, scalped and mutilated. I dismounted and sat down by the body. After recovering a little from the shock, I looked around for uncle. I found his body, also stripped, scalped and mangled, about fifty yards from my father's remains."

81-Colorado Depredations-Story Two

February 1837, James Gotcher and his two sons were away from the house and cutting wood on the river bottom when Indians attacked their house, killing and scalping a young boy and capturing a little girl. Inside the house were two ladies, Nancy Gotcher and Mrs. Crawford, and several children. The Indians rushed the house, killed Mrs. Gotcher and took Mrs. Crawford and the children captive. The men, hearing the commotion, ran to the house and attempted to fight but were cut down though one of the sons managed to rip open the throat of one of the warriors with his teeth. Mrs. Crawford and the children suffered horribly for two years in captivity before being ransomed by a trader named Spalding at Holland Coffee's station. Spalding married the widow, took the children then settled in Bastrop County.

82-Lieutenant Wren's Ambush

Around March of 1837, Captain Andrew's Rangers were enjoying the evening on the Colorado River at Coleman's Fort, also called Fort Colorado or Houston. Noah Smithwick wrote:

"The older men were smoking and spinning yards, the younger ones dancing, while I tortured the catgut. The festivities were brought to a sudden close by a bright flame that suddenly shot up on a high knoll overlooking the present site of Austin from the opposite side of the river. Fixing our eyes steadily on the flame, we distinctly saw dark objects passing and repassing in front of it. Our scouts had seen no signs of Indians, still, we knew no white men would so recklessly expose themselves in an Indian country, and at once decided they were Indians."

The Rangers found and attacked the Indian band, killing several and capturing all their horses and equipment but lost a good man in the process, Ranger Philip Martin.

83-Seguin's Cavalry

Captain Seguin moved from Camp Vigilance and established Camp Houston in late March, 1837. Captain Seguin and six of his men were searching for wild horses when on the morning of March 21st they had a run-in with seven Tonkawa Indians near Cibolo Creek. Seguin wrote:

"In the encounter we killed two of them, took two of their horses and wounded another Indian, who escaped with the balance, without any loss on our side. From appearances I have good reason to believe that they had been in among the American settlements and have no doubt committed depredations there as they had American horses with them, no arrows left in the quivers, and from other certain signs on those whom we killed I drew this conclusion."

84-Lieutenant Leandro Arreolo

Seguin had one hundred thirty men and only ninety horses and mules combined. On April 17th, a party of Tonkawas made an early morning raid on the camp, stealing thirty-two of the horses. A party of sixteen under Lieutenant Leandro Arreolo were immediately ordered to pursue them. Seguin wrote:

"They did so and overtook them at a place called Las Cuevas, about 36 miles from our camp. They had a small skirmish with them without either party being injured, retook the horse and arrived in camp with them about 12 o'clock the same day. There were about one hundred Indians."

85-Indians Steal Coleman Fort's Remuda

In April of 1837 at Fort Coleman, Lieutenant Nicholas Wren and a handful of men took the company's remuda up the creek to graze. A band of Indians swept down at a full run, yelling and whistling, stampeding the herd. A portion of the horses ran toward the fort and Ranger Smithwick opened the gate. Ranger Felix McCluskey had just mounted his horse at the fort and took out after the Indians and the rest of the herd. He was joined by Smithwick who later wrote:

"Old Isaac Castner, who had left the service and was then living at Hornsby's, had been up to the fort and was jogging along leisurely on his return. He had crossed the creek and gained the open prairie when he heard the clattering of hoofs coming in his rear. He turned in his saddle and took one look behind. The frightened animals pursued by McCluskey and myself were bearing right down on him. We had lost our hats in the wild race, and our hair flying in the wind gave us much the appearance of Indians. Uncle Isaac, who, as previously stated, weighed about 200 pounds, laid whip to his horse, which was a good animal, and led off across the prairie to Hornsby's Station, about a mile distance, the horses following in his wake and we trying to get in ahead of them. McCluskey's sense of fun took in the situation. "Be Jasus," said he, "look at him run!" and the reckless creature could not refrain from giving a war whoop to help the old man along.

Hearing the racket, the men at Hornsby's fort ran out, and seeing the chase, threw the gate open. Breathless from fright and exhaustion, Castner ran in, gasping, "Injuns.""

On the 28th of April, the Indians raided Fort Smith's remuda on the Little River, escaping with an even larger portion of Captain Daniel Monroe's Rangers horses but Lieutenant Wren was singled out to be reprimanded by President Houston for allowing his horses to graze outside the fort without mounted guards. An early valuable lesson not forgotten by later Rangers.

86/87-Post Oak Springs Massacre

May 6, 1837, a band of Indians entered the Brazos settlements killing a man named Neal, right on the edge of Nashville and then headed northwest toward the Little River Fort where they encountered and killed a five man Ranger party near Post Oak Springs.

88-Slaying of Ranger James Coryell

May 10th, 1837, a body of about two hundred Indians made a murder raid through the Brazos settlements including the Post Oak Springs Massacre. Ranger James Coryell and a few other men went down the road to Perry Creek to cut a bee tree. They were sitting around eating honey when about a dozen Caddo Indians attacked them. Coryell stood and received his mortal wounds. His companions retreated to the fort as the Indians began scalping him.

89-Clapp's Blockhouse

Captain Elisha Clapp

Painted by great-granddaughter, Wilfred Clapp

Captain Elisha Clapp was captain of the mounted Rangers, whose fortified home became the headquarters for his Rangers. On September 16th, 1836, he received orders from Sam Houston that read as follows:

"You will range from any point on the Brazos to Mr. Hall's Trading House on the Trinity. For your orders, I refer you to copies of those given to Captain Michael Costley of the N. W. Frontier, therewith enclosed for your information. The general principles of them you will find applicable to your command as well as to all officers employed on the frontier. You will detail eight men from your command for the service and place at the disposition of Dan Parker Esq., as the local situation of the frontier may require."

90-Trinity River Fort

The following excerpt is from the book, Savage Frontier, by Stephen L. Moore:

Captain Clapp's rangers, in the meantime, were ordered to secure the upper crossing of the Trinity River with a new blockhouse. The fort was advantageously located on Texas's main east-west road, El Camino Real, at the Robbins' Ferry crossing of the Trinity (at present State Highway 21 on the western border of Houston County). This fort became known as the Trinity River Fort.

Many of the above fort descriptions are from the book, Texas Forts, by Wayne Lease.

Home | Table of Contents | Forts | Road Trip Maps | Blood Trail Maps | Links | PX and Library | Contact Us | Mail Bag | Search | Intro | Upcoming Events | Reader's Road Trips Fort Tours Systems - Founded by Rick Steed |