|

||||

|

|

||||

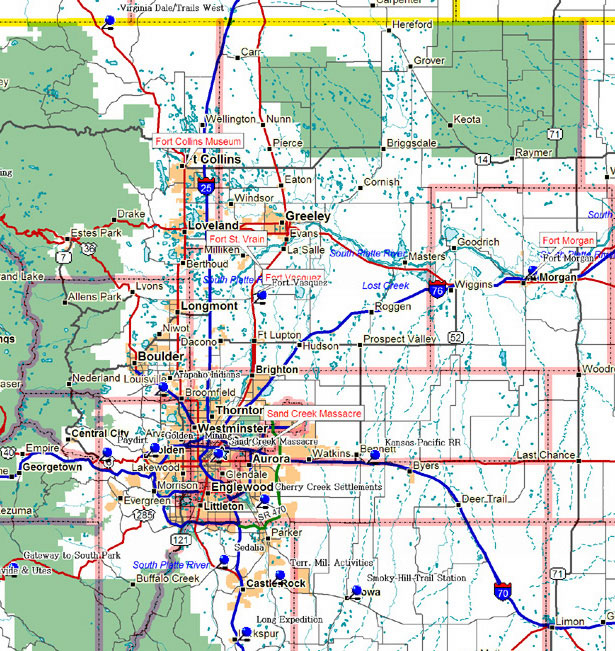

Arapaho IndiansMarker Topic: Arapaho Indians Arapaho Place NamesThe Arapahos called Longs Peak and Mount Meeker, the northernmost mountains before you, the "Two Guides." The Estes Park basin was the "Circle." Trail Ridge they identified as the "Child's Trail," because when traveling it children often had to get off their horses and walk. Big Thompson River was "Pipe River," a place where the Arapahos carved their stone pipes. Grand Lake was "Big Lake," the site of a battle between the Arapahos and Utes. Chief Left Hand (c. 1825-1864)Chief Left Hand (Niwot) was a voice for peace during the turbulent early years of the Colorado gold rush. Fluent in English, he welcomed the first gold seekers - who were trespassers on Arapaho lands - and permitted them to stay here in the Boulder Valley. On November 29, 1864, Left Hand was killed, along with 150 other Cheyennes and Arapahos, at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado by U.S. volunteer troops. His name lives on in the Peak to Peak country with Left Hand Canyon, located 15 miles north of this point; Niwot Mountain in the Indian Peaks Range directly west of here; and the town of Niwot. BoulderBritish traveler Isabella Bird was not much impressed with Boulder City when she passed through it in 1873. "A collection of frame houses on the burning plain," she described it. Founded by prospectors in February 1859, boulder was a typical gold camp - here today, perhaps gone tomorrow. It escaped extinction by the discovery of silver in the late 1860s and by the Colorado territorial legislature's decision to make boulder the home of the University of Colorado. With economic diversification and students and educators drawn form around the world, Boulder boomed and never looked back. Today, it is a famed educational and research center, and a major attraction for rock climbers and - despite Isabella Bird's bleak assessment - tourists. Cherry Creek SettlementsMarker Topic: Cherry Creek Settlements Cherry Creek SettlementsMany of Colorado's earliest settlements hugged the banks of upper Cherry Creek. These included the "mile houses," built around 1860 to supply travelers on the Smoky Hill Trail (and numbered according to their distance from the trail's terminus in Denver). Another early settlement, Russellville, attracted Colorado's first wave of gold rushers in 1858. Yet that camp lay deserted by 1860, its denizens all drawn west by rich gold strikes in the Rocky Mountains; and the mile houses became obsolete after 1870, when the Smoky Hill Trail was supplanted by the Kansas Pacific Railroad. Still, the upper Cherry Creek neighborhood remained pretty well populated, home to scattered ranches, farms, timber camps, and communities such as Franktown and Parker (the former Twenty-mile House). And during the twentieth century, Denver's suburbs grew back upstream along the creek - back to the place where, in a sense, modern Colorado began. Cherry Creek DamThe Arapahos and Cheyennes warned white settlers in the 1860s not to build along Cherry Creek. When the creek flooded ten times by 1900, the settlers understood why. The first of those deluges, in 1864, nearly swept five-year-old Denver away, and each subsequent flood brought louder demands for relief. The city began dredging out a flood-control channel in 1908, but in 1912 the creek overflowed again, inflicting another half-million dollars' worth of pain. And in 1933 Castlewood Dam (twenty-three miles upstream from here) gave way, unleashing a massive cascade of water upon Denver. Permanent flood protection finally arrived in 1950 with the completion of 2.5-mile-long Cherry Creek Dam. The $14.5 million structure more than paid for itself in 1965, averting a flood that might have caused $130 million in damage. And the reservoir it created has ranked ever since as one of Colorado's prime water-sports destinations. Twelve-Mile HouseThink of 12-Mile House as a nineteenth-century truck stop. Strategically positioned at the junction of the Cherokee and Smoky Hill Trails, it provided wagon trainers and stagecoach travelers with meals, supplies, repairs, fresh horses, overnight lodging, and other goods and services as necessary. Proprietor John Melvin built it in 1865 and soon tacked on ten guest rooms, which briefly qualified 12-Mile House as the region's largest hotel. It was unquestionably the largest of the "mile houses" that lined the Smoky Hill Trail at roughly four-mile intervals. With its tavern, post office, and half-mile racetrack, it evolved into a rollicking recreation center for local ranchers and farmers; special holiday celebrations drew day-trippers from as far away as Denver. In 1880 business finally slowed to a trickle, and the Melvins closed 12-Mile House and went into ranching. TrailsThree roads will be traveled next summer. The Arkansas by those from the south and southwest, the Smoky Hill by the foolhardy and insane, and the Platte by the great mass of migration. In the mid-nineteenth century, two busy frontier trails followed this part of Cherry Creek. One, the Cherokee Trail, was forged in 1849 by a party traveling from Arkansas to the California gold fields. This road paralleled the Arkansas River west, turned north along Fountain and Cherry Creeks, and eventually veered west again in present-day Wyoming. It remained busy into the 1870s. The other trail, the Smoky Hill, carried many of Colorado's first gold-rushers in 1859. This dry, desolate route passed through Cheyenne and Arapaho territory, roughly following today's U.S. 40 and Colorado 86, and became known as the Starvation Trail after the grisly demise of one unfortunate party. As a result, travelers generally avoided the Smoky Hill until 1865, when stagecoach lines began running service over the route. In 1870 Colorado's railroad era began, and the trails quickly fell silent, their twenty-year heyday over. Indians of Colorado's High Plains Kiowa and Comanche Indians migrated to these prairies in the 1700s, followed by Cheyennes and Arapahos in the early 1800s. The region's infinite grasslands, thick bison herds, and brisk fur trade made for prosperous, if not entirely harmonious, living; the allied Cheyennes and Arapahos warred frequently against the Comanches and Kiowas (who gradually moved south of here) until 1840, when the tribes agreed to a historic peace. In 1851 the United States granted most of eastern Colorado to the Cheyennes and Arapahos, but when gold rushers began stampeding through here after 1859, strife erupted anew, this time between whites and Indians Though they fought for their homeland, the Indians were badly outgunned and outnumbered; by 1869 they had been banished from Colorado's plains forever. Fort MorganMarker Topic: Fort Morgan Fort VasquezMarker Topic: Fort Vasquez As trappers and explorers, Louis Vasquez and Andrew Sublette helped build the lucrative fur trade. But by 1835, when they raised Fort Vasquez midway between Fort Laramie and Bent's Old Fort along Trapper's Trail and went into business for themselves, the fur industry was nearly played out. Three nearby forts competed for dwindling trade, and the tow veteran mountain men, unable to turn a profit, sold the post in 1841 for just $800. Failing to collect even that sum, the new owners went bankrupt and abandoned the place in 1842. In later years a series of tenants - calvary units, stagecoach operators, and mail riders - occupied the structure for the short periods, but after the 1860s the only visitors to Fort Vasquez were curious homesteaders and tourists. "We soon came to the ruins of an old Fort, where we halted for a few moments. This is made of mud or "Dobey," the enclosure is about 100 feet square. The walls about 12 feet high. Upon two corners stand the round guard house running about five feet higher. Around the walls are "port Holes" and so made as to shoot from them in any direction. The old walls are now crumbling away." In the 1930s the New Deal's Works Progress Administration rebuilt the crumbling outer walls of Fort Vasquez. Three decades later, the Colorado Historical Society launched an archaeological study to reconstruct daily life inside the complex. Painstaking excavations revealed roughly a dozen rooms around a large interior plaza. Visiting traders kept their pack animals in wooden stalls along the east wall, cooked and dine in a communal kitchen, warmed themselves beside brick fireplaces, and conducted business in large trading rooms. Storage chambers, a smithy, and the two proprietors' living quarters completed the fort. The rubble of the old fort yielded a wealth of buttons and beads, the currency of the fur trade - long-lost funds from forgotten transactions. Gateway to South ParkMarker Topic: Gateway to South Park Gateway to South ParkMountainous chains and peaks in every variety of perspective, every hue of vista, fringe the view... the whole Western world is, in a sense, but an expansion of these mountains. As an important route from the east into Colorado's Rocky Mountains, Kenosha Pass has long served as a gateway to good fortune (and its share of hard luck). Through this portal the Utes gained access to the giant game herds of South Park. And, in the early nineteenth century, fur trappers came here in search of pelts. The gold strikes of the 1860s flung the door wide open; miners poured through by the thousands, bound for Fairplay and other diggings. As the rough trail from Denver widened into a wagon road, then joined by a railroad, Kenosha Pass became one of the Rockies' main ports of entry, funneling traffic to Leadville, Breckenridge, Aspen, and beyond. From this summit, with the mountains parading across the horizon, travelers must have envisioned their destinies stretching out before them, as if they had reached the threshold of opportunity. South Park RanchingThe whole of the plains and the parks in the mountains of Colorado are the finest of pastoral lands... Stock fattens and thrives on them the year round. Over time, South Park's grasses proved more valuable than its gold mines. The bison and other game that for centuries had thrived in these pastures gave way after 1860 to sheep and cattle - some 60,000 head by 1885. Local ranchers found ready markets at nearby mining camps, and after 1879 they shipped their stock east on the Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad. Nearly 150 outfits operated here, though the larger ones were usually more prosperous - Samuel Hartsel's ranch alone occupied 12,000 acres. The harsh winters of the late 1880s thinned the herds, and ensuing years brought fluctuating prices, the railroad's demise, and government grazing regulations. In the late twentieth century, thirsty Front Range cities began buying up South Park's water draining the area of this precious resource. Yet, ranching holds on. It still remains an important part of the basin's economy - a lasting piece of the area's heritage. Dake Charcoal KilnsLeadville's silver kings would not have reigned without the labors of humble Dake. This short-lived community, founded two miles northeast of here in 1883, produced charcoal to fuel the smelters of Denver and Leadville. Nearly all three hundred residents were thus employed - most in chopping down trees, others in tending the twenty-seven kilns that cooked the timber to produce charcoal. The sooty fuel had a lowly reputation, but since the preferred alternative, coke, was expensive and difficult to keep in supply, Dake never wanted for customers. The charcoal operation churned out fuel by the ton, almost completely stripping Kenosha Pass of trees in the process. But when the silver kings fell, so did Dake; the Panic of 1893 shuttered the smelters, and by the end of that year the charcoal town lay abandoned. Founded in 1859, Breckenridge experienced its share of boom and bust - including the discovery of Colorado's largest gold nugget in 1887, the end of dredge mining in 1942, and its success as a ski resort and year-round destination. Come walk its National Register Historic District (strict building codes have preserved many Victorian-era buildings) or visit the Summit County Historical Society museum or one of its regional properties. Golden - MiningMarker Topic: Golden - Mining GoldenOne story goes that Golden takes its name not from the metal but from failed prospector Thomas Golden, whose fruitless quest for riches ended here in 1858. Incorporated in 1860, this fast-growing mining supply center competed fiercely with Denver to become the primary gateway to the Rockies. In addition to housing the territorial capital from 1862 until 1867, Golden anchored a far-flung transportation network; the Colorado Central Railroad brought huge shipments of ore here from the gold camps, and the city grew into a bustling hub of train yards, smelters, brickworks, and factories (including the now now-famous Coors brewery). Although Denver ultimately won the competition for regional dominance, Golden lived up to its name. And it triumphed in a larger sense, retaining its distinct character and independence even as its old adversary sprawled to its doorstep. W.A.H. Loveland & the RailroadIn addition to helping found Golden, W.A.H. Loveland was the town's most daring strategist in its contest against Denver. He launched the Colorado Central Railroad in 1870, intending to squeeze Denver out of the freight business and thus establish Golden as Colorado's commercial capital. It was a long shot, but Loveland nearly pulled it off by side-stepping creditors, defying legal injunctions, and even once having a judge kidnapped to keep the railroad out of receivership. Loveland's Denver rivals and their powerful ally, New York financier Jay Gould, couldn't help but be impressed; he nearly beat them at their own game, and only their superior wealth and numbers enabled them to prevail. Though Loveland's master plan for Golden failed, few Colorado cities have ever enjoyed a more determined advocate. MiningIn addition to serving high-country gold and silver camps, Golden developed mines of its own - coal and clay operations - and though the output hardly glittered, it gilded the city's economy for decades. Two coal-digging enterprises opened near here in the 1870s, primarily to fuel Golden's locomotives and smelters. Richer still were the local clay deposit, which ran under the heart of town and yielded tons of material for tiles, dishware, and pottery - and, above all, bricks. Stamped "Golden" to certify their high-quality origin, these durable slabs built dozens of prominent Colorado buildings, among them the Governor's Mansion in Denver. The clay's high firing point made it particularly useful for industrial purposes (such as smokestacks and furnaces) and, after World War II, defense-related applications. Still heavy producers, Golden's clay pits have outlived the mountains' gold veins by more than a century. Colorado School of MinesThe giant white "M" on the hillside west of town stands for "Mines" - as in Colorado School of Mines, one of the nation's top engineering universities. The roots of the oldest state-supported institution of higher learning date back to 1869, when an Episcopal bishop founded a small school of metallurgy in Golden. Recognizing the value of such an academy for Colorado's mining industry (and for their town), local leaders pushed for state funding, and in 1874 the Territorial School of Mines gained its charter, with W.A.H. Loveland, George West, Edward Berthoud, and other notables on the inaugural Board of Trustees. The curriculum originally focused on gold and silver assaying but expanded over the years to include petroleum exploration, environmental engineering, even interplanetary mining. One thing that hasn't changed is the venerable "M," proudly maintained by Mines students since 1908. Camp George WestCamp George West honors one of Golden's founding settlers. West (1826-1906) tirelessly promoted the town in his Colorado Transcript (the state's longest-running weekly paper) and fought to establish the Colorado School of Mines here. He also served a term as Colorado's adjutant general, during which he recommended that a troop troop-training facility be established at the foot of South Table Mountain. The suggestion led in 1903 to the founding of the State Rifle Range. Renamed for West in 1934, the complex over the years has served National Guardsmen, Army reservists, state law-enforcement personnel, and civil defense units; during World War II it stored munitions and housed German prisoners of war. Though it donated half its land to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in 1981, Camp George West continues to serve a variety of state and federal agencies. Kansas Pacific RailroadMarker Topic: Kansas Pacific Railroad/Ten Miles in a Day August 15, 1870, was perhaps the greatest single day of railroad building in history. The Kansas Pacific tracks had surged to within fifty miles of Denver; a second construction team, advancing eastward from the city, stood just over ten miles distant. At dawn on this notable day an American flag and a keg of whiskey were placed halfway between the two crews, and the rhythmic calls of the gandy dancers commenced. By three in the afternoon the workers had bridged the gap; they laid ten miles of track in ten hours, a feat not matched before or since. Moreover, the Kansas Pacific made it possible to ride coast to coast without ever leaving the rails - the Union Pacific still lacked a bridge over the Missouri River and required passengers to be ferried across at Omaha. Long ExpeditionMarker Topic: Long Expedition Long Expedition, 1820In 1820, Major Stephen H. Long trekked to the Rocky Mountains seeking the headwaters of the Platte, Arkansas, and Red rivers. When his 22-man party passed through area on July 9, the men marveled at the lush mountain scenery and spectacular landforms of the area. On July 12, the expedition paused near present-day Colorado Springs long enough for botanist Edwin James to scale Pikes Peak - declared "unclimbable" by Zebulon Pike only fourteen years before. Long never found the headwaters he sought, but the many species of plant life he collected busied scientists for years and his description of the Great Plains as a "Great American Desert" forever fixed itself upon the American mind. A Delightful Discovery"We are delighted with our first entrance of what we may now call the Arkansas country - cool water from the mountain, numberless beaver dams and lodges. Naturalists find new inhabitants, the botanist is at loss which new plant he will first take in hand - the geologist grand subjects for speculation - the geographer and topographer all have subjects for observation." Mountain Men/Trapper's TrailYour journey along I-25 between present Pueblo and Greeley follows a centuries-old trail. Native peoples, Spanish and French explorers, American trappers - all used it at various times. By the 1840s most westerners knew it as the "Trappers' Trail," named for the storied mountain men who trapped in this region from the 1820s and moved frequently between Bent's Old Fort on the Arkansas River to fur posts on the South Platte. A Breed ApartThey wandered the uncharted Rocky Mountains, they went in harm's way, and they captured the imagination of Americans, then and now. But the mountain men were neither so free nor so independent as their legend insists. They toiled at the end of a long economic chain that stretched from the icy beaver ponds of the Rockies to the uncertain fashion markets of New York and London. Then in the 1840s, the supply of beaver ran out, and hat fashion changed from fur to silk. Suddenly, the day of the mountain men was done. Kit Carson became a guide, Jim Baker a rancher, and Thomas Fitzpatrick an Indian agent. Others were unable to fit in, forever of the move, always on the fringe of society, misfits to the end. PaydirtMarker Topic: Paydirt PaydirtUntil 1859 gold existed mainly in rumor in Colorado - but it was a persistent rumor, dating back to the 1500s. Rumor became reality for thousands of doubters when, in a series of significant strikes beginning with George Jackson's discovery near present-day Idaho Springs in January, miners began to find bona fide lodes - not just a sackfuls of dust, but vast fortunes. Though not the first strike, John Gregory's find near present-day Central City in May brought thousands of miners up Clear Creek Canyon who had begun to dismiss the rumor as a hoax. The Jackson and Gregory discoveries, among others, marked the beginning of the real gold rush, bringing tens of thousands of settlers to Colorado. John Gregory was not among them, however; unsettled by fame and fortune, he sold his claim in 1862 for $21,000 and vanished from history. His lode eventually produced $200 million worth of gold. SmeltingFinding Colorado's gold was one thing; extracting it profitably was another problem entirely. Most of it was locked up in maddeningly complex ores, and there existed no efficient, cost-effective means of distilling out the paydirt. Not, that is, until 1867, when a professor named Nathaniel P. Hill perfected smelting. Adapting a Welsh mining process, Hill used high heat and pressure to draw out the precious metals. His innovation threw open the West's mineral vaults and launched the era of industrial-scale, hard-rock mining; it also established Colorado as America's nineteenth-century ore-processing center. Mines throughout the West shipped their output here - first to Hill's Boston and Colorado Smelter (which opened at Black Hawk in 1868), later to massive refining complexes in Denver, Leadville, and Pueblo. Hill eventually became Colorado's third U.S. senator - and smelting emerged as one of the state's most important industries. Colorado Central RailroadAs you drive along this stretch of U.S. 6, you are often traveling on the former bed of the Colorado Central Railroad, the first line to build tracks into Colorado's Rocky Mountains. Its route from Golden to Black Hawk opened in 1872, providing what was then Colorado's richest gold district with rapid, cheap, high-capacity freight service. By decade's end the CCRR stretched beyond Silver Plume (25 miles west of here) and eastward to prairie ranches and farms, integrating the disparate parts of Colorado's young economy. It also carried day-trippers from Denver to view the scenic wonders of the canyon, to picnics in the mountains, and to the dance pavilion at Beaver Brook (two miles east of here). The line stayed busy until the 1920s, when dwindling mine yields and increased auto traffic sent railroading into decline. The last train to Black Hawk ran in 1941. Clara BrownUnlike most of Colorado's gold-rush pioneers, Clara Brown had already reaped her bonanza - freedom, which she purchased from her Kentucky slavemaster for $120 in 1856. She reached Central City in 1860 at fifty-plus years of age, set up shop as a laundress, saved enough to invest in some mining claims, and quickly became a prosperous woman. But she shared her wealth freely, spending much of it to build churches and schools, aid the destitute, and help ex-slaves establish new lives in Colorado. More dedicated to philanthropy than to business, she gave away most of her fortune; bad luck and economic downturns claimed the remainder, leaving Clara Brown broke and living on a pension. The former slave died penniless in 1885. But few Coloradans bequeathed a richer legacy. Chinese in ColoradoBetween two and three hundred Chinese immigrants settled near Central City in the 1870s, forming the state's second-largest Chinese community (behind Denver). Most were former railroad construction workers who moved here in search of better prospects. But then, prospects for Chinese in the West were always limited by language barriers, discriminatory laws, and outright racism. Chinese mine workers in Central City earned lower wages than European immigrants did, and their only opportunities to mine for themselves were on leased claims that others had given up for dead. Yet they made those claims pay. This pattern repeated itself throughout the state: Chinese made the most of less-than-ideal circumstances, carving out livings as laborers, miners, and entrepreneurs - and doing much of the hard work involved in building Colorado. Though most of the early Chinese settlers eventually left, the descendants of those who remained welcomed new Chinese and other Asian immigrants to the state, particularly in the late twentieth century. Chin Lin Sou"To his memory is due much respect, for he was a true pioneer." Few Coloradans bridged the gap between Chinese and American culture as successfully as Chin Lin Sou. A native of southeastern China, he came to Colorado via California, arriving here in 1870 to supervise construction crews for the Denver Pacific Railroad. After migrating to Central City to manage Chinese mine laborers, Chin began operating mines of his own (on claims leased from white owners), and he soon acquired interests in other mountain towns and in Denver. His success created many opportunities for the Chinese community, but Chin also reached across racial boundaries to forge friendships and ties with white businessmen. Although a federal law stripped him (and all Chinese) of U.S. citizenship in 1882, Chin remained an esteemed Colorado resident until his death in 1894. Marchers carried both the Chinese and U.S. flags in his funeral procession. Other AttractionsA major gold discovery in Central City/Black Hawk in May 1859 forever changed the future of Colorado. Today, this National Historic Landmark District offers visitors ample opportunity to explore the region's past. The Gilpin County Historical Society operates three museums in Central City: the Gilpin History Museum, the Thomas House, and the Coeur d'Alene Mine Shaft House. The Central City Opera House, opened in 1878, still plays host to a summer season of operatic performances. Visit the Harvey House and the Teller House, historic homes on the National Historic Registry, for a glimpse into the lives of the city's well-heeled residents. Just northeast of Black Hawk, in Golden Gate Canton State Park, Frazer's Barn and the Bootleggers' Cabin offer glimpses into the frontier past of Gilpin County. In Black Hawk, the Lace House offers and example of the Victorian architecture popular among that town's residents in the nineteenth century. Central City/Black Hawk also offers limited stakes gambling and other casino-oriented entertainment for visitors. To the South of Clear Creek Canyon, Idaho Springs, the site of George A. Jackson's January 1859 gold strike, a thriving gold camp, and now a National Historic District, saw its population jump to 12,000 during the 1860s. It was also a smelting center and by 1903 thirty-one treatment plants dotted the area. After the 1870s, visitors came to soak in the mineral hot springs whose water also was bottled and sold across the country. Today, the Argo Gold Mill, Mine and Museum, the Edgar Mine, the Heritage Center Museum, and the Underhill Museum interpret Idaho Springs mining and frontier history for visitors. Sand Creek MassacreMarker Topic: Sand Creek Massacre Sand Creek Massacre/Civil War MonumentThe controversy surrounding this Civil War Monument has become a symbol of Coloradans' struggle to understand and take responsibility for our past. On November 29, 1864, Colorado's First and Third Cavalry, commanded by Colonel John Chivington, attacked Chief Black Kettle's peaceful camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians on the banks of Sand Creek, about 180 miles southeast of here. In the surprise attack, soldiers killed more than 150 of the village's 500 inhabitants. Most of the victims were elderly men, women, and children. Though some civilians and military personnel immediately denounced the attack as a massacre, others claimed the village was a legitimate target. This Civil War Monument, paid for by funds from the State and the Pioneers' Association, was erected on July 24, 1909, to honor all Colorado soldiers who had fought in battles of the Civil War in Colorado and elsewhere. By designating Sand Creek a battle, the monument's designers mischaracterized the actual events. Protests led by some Sand Creek descendants and others throughout the twentieth century have since led to the widespread recognition of the tragedy as the Sand Creek Massacre. SedaliaMarker Topic: Sedalia History of SedaliaPioneer rancher John Craig built his "Round Corral" about a quarter mile from here in 1859 next to a well-traveled road along Plum Creek. Other settlers followed, and when the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad pushed through here in 1871, most of these neighbors moved slightly north to the present townsite. Originally called Plum, then officially renamed Sedalia in 1882 (after the postmaster's Missouri hometown), it became an important logging hub - timber from the forests to the west built much of Denver and Colorado Springs. Dairy farms, a coal mine, and a cigar factory also prospered here, but these enterprises declined along with railroading during the mid-twentieth century. Although a 1965 flood damaged the town, the stability of area farms and ranches helped Sedalia withstand the currents of change and prosper into the twenty-first century. Sedalia and the RailroadThe mighty Denver & Rio Grande Railroad was in its struggling infancy when it put a station here in 1871, just a few months after the first tracks left Denver. The D&RG's first Denver-bound freight train - several carloads of timber - originated here, and Sedalia evolved into one of the line's early freight centers, as well as a key source of building material for the rapidly expanding railroad. In 1881 Sedalia gained a second line, the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe, and by 1900 it had five, creating a constant bustle on the trackside cargo docks. The constant comings and goings of the locomotives helped drive Sedalia's prosperity until about World War II, when rail shipping began to give way to trucking. But trains still rumble through here, daily reminders of Sedalia's early history. Frenchman Marquis Victor arrived in Sedalia in 1874. By 1876, he was able to purchase "...the finest brick house in the community..." His home often doubled as a dance hall and meeting space for fraternal organizations as well as public gatherings. George Manhart's store was a Sedalia institution offering a wide array of merchandise as well as a place to gather for local news and gossip. By 1890 the store (now a substantial brick building) was heated by steam, lighted by its own electrical plant, and eventually boasted the town's first phone booth. In 1887, the Atchinson, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad constructed its own right-of-way from Denver to Pueblo with its tracks virtually paralleling the D&RG's. At two locations the tracks actually crossed each other on overhead bridges. Volunteer FireNineteenth-century Coloradans dreaded fire more than any other natural disaster; one stray spark could (and often did) destroy an entire town. But most rural communities couldn't afford to pay full-time firefighters, relying instead on volunteer efforts. These evolved from spur-of-the-moment "bucket brigades" (where citizens lined up and passed pails of water from hand to hand) into quasi-professional organizations with permanent rosters and full supplies of axes, ladders, pumps, and hoses. The volunteer departments made a huge difference: In addition to sparing their communities from devastating blazes, they served as social and civic hubs, often competing in firefighting exhibitions against outfits from rival towns. But a good hose company was more than a point of pride; it meant real security. Volunteer fire departments still protect much of rural Colorado, where fire remains a prominent hazard. Pike National ForestBy 1890, after two decades of intensive logging, the forests west of Sedalia had been stripped of marketable timber. Lest they vanish altogether, President Benjamin Harrison included the remaining stands in three timber preserves, which in 1907 were combined into the 1.1 million-acre Pike National Forest. Federal oversight of logging, grazing, and mining drew strong resistance at first, but the outcry subsided as the benefits of resource management - including firefighting, soil conservation, and watershed protection - became apparent. In the 1930s, Civilian Conservation Corps workers helped build erosion control dams, picnic areas, and the scenic Rampart Range Road (Colorado 67). Ensuing decades brought ever-increasing crowds of outdoor recreationists to the National Forest to camp, view wildlife, fish in the South Platte River, or just to find some solitude. Over the last half of the twentieth century, the Pike has consistently ranked among the nation's ten most heavily visited national forests. Smoky Hill Trail StationMarker Topic: Smoky Hill Trail Station Frontier CommunicationKiowa was originally named after its postmaster, Henry Wendling. Such identifications were common among Colorado's frontier hamlets,, where the post office often was the town. Widely dispersed settlers would congregate at these stations (usually housed in a ranch of general store) to stay in touch with each other and the outside world. As communities grew, residents kept informed via the local newspaper, which recorded hometown births, deaths, calving, paintings, fence-mendings, and well-diggings along with state and national events. Kiowa's most notable publication was the Divide Review, which owner Floyd Lemon produced single-handedly from 1920 to 1960 without missing an edition. All these modes of correspondence - along with the telephone, which went into service here just after 1900 - eased the loneliness and isolation of rural life and helped create a sense of community among distant neighbors. Trail Under SiegeIndians of Colorado's High Plains Kiowa and Comanche Indians migrated to these prairies in the 1700s, followed by Cheyennes and Arapahos in the early 1800s. the region's vast grasslands, thick bison herds, and brisk fur trade made for prosperous, if not entirely harmonious living; the allied Cheyennes and Arapahos warred frequently against the Comanches and Kiowas (who gradually moved south of here) until 1840, when the tribes agreed to historic peace. In 1851 the United States granted most of eastern Colorado to the Cheyennes and Arapahos, but when gold rushers began stampeding through here after 1859, strife erupted anew, this time between whites and Indians. One tragic episode (the 1864 Hungate Massacre) occurred about fourteen miles northwest of Kiowa. Though they fought for their homeland, the Indians were badly outgunned and outnumbered; by 1869 they had been banished from Colorado's plains forever. Smoky Hill TrailDenver-bound travelers could save distance and time on the Smoky Hill Trail - but only if willing to risk death by Indian attack. The trail bisected the Cheyennes' and Arapahos' treaty-granted homeland, and the tribes kept it under siege almost continuously in the late 1860s. One branch earned notoriety as the "Starvation Trail" after an 1859 gold rush met a disastrous end, but the Smoky Hill became a main highway in 1865 when the Butterfield Overland Dispatch began running stagecoaches over it. With fortified stage stops every few miles (including one right here), the route was reasonably well defended, but passengers never rested easy; the war cry might go up at any moment. Enough people took their chances, though, to keep the Smoky Hill Trail busy until the 1870 opening of the Kansas Pacific Railroad. Regional MapIn 1858, about five miles south of present-day Franktown, William Green Russell and his party discovered gold. Russellville soon grew up at the site of the find. A hotbed of military activity during the Civil War, little evidence of this early mining camp remains today. Long a landmark on the Trappers' Trail, Castle Rock was named by a gold seeker in 1858. In 1820, Stephen H. Long led an expedition that traveled through present-day Douglas County. While in Palmer Lake, this expedition made the first recording of what would become Colorado's state flower, the Rocky Mountain Columbine. Territorial Military ActivitiesMarker Topic: Territorial Military Activities Territorial Military ActivitiesFranktown and Russellville both had small stockades in the early 1860s to protect this region from Confederate raiders, who hoped to tip the balance of the Civil War by gaining control of Colorado's gold fields. Manned by area residents (John Frank Gardner "commanded" the Franktown garrison), these local defenses supported Colorado's federal volunteer troops, who frequently patrolled the Jimmy Camp Trail. A group of volunteer cavalry camped near Russellville in 1863 while searching for Southern guerrillas, and six Texans (the infamous "Reynolds gang") were executed there the following year. Territorial troops fought their most significant battle at Glorieta Pass in northern New Mexico, where the First Colorado Regiment helped turn back a sizable Confederate force in March 1862. Though far removed from the Civil War's main theaters, Colorado still had a hand in winning it. History of FranktownFranktown takes its name from James Frank Gardner, a would-be gold miner who built a squatter's cabin four miles north of here in 1859. A popular rest stop on the busy Jimmy Camp Trail (which followed Cherry Creek into Denver), "Frank's Town" was designated the seat of Douglas County in 1861; the settlement moved to its current location two years later. Though railroads made the trail obsolete after 1870, and the county offices moved to Castle Rock in 1874, Franktown remained a ranching and farming hub, held together by its church, school, grange, and handful of businesses. It never incorporated, and during the twentieth century no more than a hundred people called it home, but that's how the locals liked it. Even as suburban sprawl surrounded it in the 1990s, Franktown resisted efforts to develop, maintaining a distinctly rural identity. The GrangeFranktown's strong agricultural roots made it a natural fit for the grange, a cooperative farmers' movement that swept rural America in the mid-1870s. Several dozen chapters formed in Colorado, including the Fonder Grange (founded near here in 1875) and its successor, Pikes Peak Grange No. 163 (established in Franktown in 1908). Both belonged to the statewide grange organization, which set up credit unions, insurance programs, and other services, and to the national grange association, which pursued long-range political goals. But it was the local chapters that really affected farmers' lives. The dances, holiday picnics, and town meetings they sponsored helped sparsely populated communities forge a sense of identity. Still active today, Pikes Peak Grange No. 163 occupies its original hall, which stands just north of here and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Timber IndustryFrontier travelers often rejoiced upon reaching the timbered ridge just south of Franktown; it was the first woodland they encountered after hundreds of miles on the prairies. Early settlers in Colorado appreciated the forest, too-as a source of building material. Known as "the Pinery," it provided fast-growing Denver and other towns with most of their lumber during the 1860s. Several sawmills buzzed nonstop in and around Franktown, barely able to keep up with the demand. In the early 1870s, the Pinery supplied railroad ties to the Kansas Pacific and Denver & Rio Grande, both of which were laying tracks within twenty-five miles of here. Those routes eventually opened larger forests to exploitation and helped bring down this region's timber industry. By 1880, Franktown's sawmills had gone silent, but they had already left their mark: Pinery lumber built much of early Colorado. Castlewood DamFrom the day it opened, Castlewood Dam was a catastrophe waiting to happen. Built in 1890, about five miles south of here on Cherry Creek, the barrier stored enough water to irrigate 30,000 acres of farmland-or would have, if it hadn't leaked so badly. The seeping began the year the dam was completed and was serious enough that a hundred-foot section crumbled in 1897. Although its builders vouched for the structure's integrity, the dam continued to leak sporadically for decades. Finally, on August 3, 1933, the inevitable happened: Castlewood collapsed, sending a billion-gallon torrent toward Denver. Only two people drowned, thanks to a switchboard operator's life-saving calls, but the flood devastated farms in this area and tore out six bridges in Denver, thirty miles downstream. The dam's remains can still be visited in nearby Castlewood Canyon State Park. RussellvilleFor a few exciting months, Russellville felt like Colorado's gold-rush capital. The town rose five miles southeast of here in late 1858, after William Green Russell discovered a few gleaming specks in his pan at Russellville Gulch. His find brought a horde of prospectors-an advance wave of the Pikes Peak gold rush. With its busy placer diggings and clusters of tents, Russellville brimmed over with promise; but its nuggets, although pure, were too scarce to make fortunes. In the spring of 1859 the real gold rush began in the Central Rockies, about seventy-five miles northwest of here, and Russellville's boom abruptly busted. Nearly deserted, the settlement survived for a time as a passenger way station, but by 1880 this hopeful gateway to the gold fields had become a ghost town. Virginia Dale/Trails WestMarker Topic: Virginia Dale/Trails West Virginia DaleAt midnight we drew up at Virginia Dale Station... Nature, with her artistic pencil, has here been most extravagant with her limnings. Even in the dim starlight, its beauties were most striking and apparent. The dark evergreens dotted the hillsides, and occasionally a giant pine towered upward far above its dwarfy companions, like a sentinel on the outposts of a sleeping encampment. Once a rowdy stop on the Overland Stage, Virginia Dale lies in a picturesque valley of gentle meadows and high, rocky cliffs. Jack Slade" I turned quickly and looked into the muzzle of two revolvers. I had met Slade before, but now we were properly introduced."- 1880s reminiscence, Frank G. Bartholf, Larimer County commissioner Trouble seemed to follow Jack Slade everywhere. He committed his first murder in Illinois at age thirteen, allegedly killed a drinking buddy in Wyoming, and was said to have sliced off a man's ears in eastern Colorado before pumping him full of lead. But he had one legitimate talent - he ran an efficient stagecoach operation - and as long as the line functioned smoothly and the mail arrived on time, Slade's employers could overlook his bullying and boozing. He came to Virginia Dale in 1862 as the Overland Stage Line's division agent; inevitably, though, trouble found him here, too. Suspected of robbing $60,000 from one of his own stages, Slade was fired and sent packing to Montana, where he immediately made new enemies. He died in 1864 at the end of a vigilante's noose. Trails West/The Cherokee Trail"We set out from this place [the Cache la Poudre] without road, trail, or guide through the plains and hills. We succeeded well, from 15 to 20 miles a day, for some time until we got within some 40 or 50 miles of the North Fork of the Platte, when the hills became worse and we had to detain more times hunting out the route and working it." Fourteen California-bound prospectors passed right through here in 1849, roughly following present-day U.S. 287. But rather than continuing north to join the Oregon Trail (the continent's main east-west thoroughfare), these impatient travelers forged a new route across the desert flats of southern Wyoming, parallel to today's I-80. They eventually picked up the Oregon Trail at Fort Bridger, having shaved 150 miles off the journey. Their road (dubbed the Cherokee Trail, after the gold party's Indian members) lacked sufficient water and forage for plodding wagon trains, and thus it drew meager emigrant traffic. But its time-saving trajectory met the needs of U.S. postal officials, who adapted the old Cherokee road to create a new frontier mail route. Renamed the Overland Trail, it emerged in the 1860s as one of the nation's main westward conduits. The Overland TrailUnlike the Oregon, Santa Fe, and Mormon trails, the Overland Trail was a carefully planned and maintained highway - in essence, a government road. Congress designated it the West's official mail route in 1861 and awarded the contract to the Central Overland California & Pikes Peak Express, which sold it to Ben Holladay in 1862. With stations every ten to fifteen miles offering protection and provisions, the 1,900-mile route was less vulnerable to Indian attack than the more established Oregon Trail, and its South Platte River approach provided excellent access to fast-growing Denver. When fights between the U.S. Army and northern Plains tribes grew bloody in the mid-1860s, pioneer traffic shifted from the Oregon Trail to the better-defended Overland Trail. From then until the Union Pacific Railroad's 1869 debut, the way west came right through Virginia Dale. |

||||

|

||||