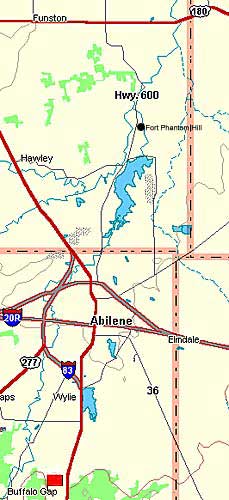

Fort Phantom Hill: Ten miles north of present day

Abilene

This fort was established on Nov. 14, 1851 as a unit in a chain of

forts from the Red River to the Rio Grande, to defend frontier settlers

and West-bound 49'ers. Officially called the "Post on Clear Fork

of the Brazos", its everyday name became "Phantom Hill",

either from prevalent mirages or sighting of ghostly Indian in moonlight

. .

Phantom Hill like most forts in northwest Texas was exceptional only

in hardships shortages and supplies. Fortunately for Phantom Hill's

short span, only one major Indian occurrence was recorded. A buffalo

hunt brought twenty-five hundred Comanches near, they scornfully observed

the construction of the fort. A message was sent to Major Sibley, promising

when the grass became good again they would be coming back down to whip

him.

From the book, Along Texas Old Forts Trail, by Rupert N. Richardson,

B.W. Aston, Ira Donathan Taylor:

On approaching the post from the north you will see the remaining

chimneys standing like sentinels on what looks like a formidable hill

overlooking the Clear Fork of the Brazos. As one nears, the hill it

disappears and becomes a gentle slope, barely perceptible when one

arrives; thus one of the stories of how the post got its name. A second

account has to do with a nervous sentry firing on what he thought

was an Indian on the hill. A following investigation failed to discover

the presence of any Indians, and one of the troopers suggested that

the man had seen a ghost. Whatever the case, Maj. Gen. Persifor F.

Smith, commanding the Fifth Military Department (Texas), in General

Orders Number 91 ordered a post established "at, or in the immediate

vicinity of, a point known as Phantom Hill" on the Clear Fork

of the Brazos. (Richardson 1963, 68).

Maj. J.J. Abercrombie was given the task and arrived on the scene

on November 14, 1851. His introduction to the region was not kind, as

exposure to a wet norther cost him one teamster and twenty horses, mules,

and oxen-all frozen to death. Not only was the environment hostile,

but Major Abercrombie soon discovered that the site had been chosen

from an earlier survey on the assumption that the needs for the construction

and maintenance of a post-wood and water-were available. He immediately

reported to his superiors that neither wood for construction nor water

suitable for men or animals was to be had. Unfortunately, General Smith

had left the field to escort an ill General Belknap to Fort Washita,

and could not be contacted for several weeks. There was no one who could

change the orders. Abercrombie had to make the best of a bad situation,

and construction of Fort Phantom Hill began.

The hardships of surviving that first winter are well described by

Lt. Clinton W. Lear in a series of letters to his wife in New Orleans.

Somewhat of a romantic, Lieutenant Lear was taken by the beauty of the

area with its abundant fish, deer, wild turkeys, and bear. He felt it

unfortunate that such a beautiful place had so little to offer a military

post. He said that he spent most of his time searching for timber-the

best stand for construction purposes was six miles away. The winter

of 1851-1852 was spent in tents, pitched in a grove of black jacks.

The most immediate problem-water-was solved when a spring was found

nearby, but it disappeared during the dry summer. A well of good water

was dug some four miles from the site. (Richardson 1963, 89-91).

With the coming of summer a permanent post was begun, when a good stone

quarry was located on the east bank of Elm Creek about two miles distant,

and with the arrival of a stone mason. A stone storehouse, creditable

stone quarters for the commanding officer, a hospital of rude logs,

and a half dozen or more quarters for officers built principally of

logs (jacal huts of upright poles interlaced with bough and daubed with

mud) were built.

Fort Phantom Hill was garrisoned by Companies B, C, E, F, and K of

the Fifth Infantry. The plans called for one hundred horses to mount

one company of infantry for scouting. The military failed to understand

at the time that putting an infantryman on a horse did not make a cavalry.

That problem, however, was not Abercrombie's as he was transferred out

on April 27, 1852, and was replaced by Ltc. Carlos A. Waite. On September

23, 1853, four companies were transferred out to be replaced by Company

I of the Second Dragoons, bringing post strength to 139 men. Maj. H.H. Sibley took command of the post then, but only stayed until March

of 1854, when he was replaced by Lt. N.C. Givens. Lieutenant Givens'

command was short-lived, as the troops finally shook the dust of Fort

Phantom Hill from their shoes when they marched out on April 6, 1854.

(Richardson 163, 92-95).

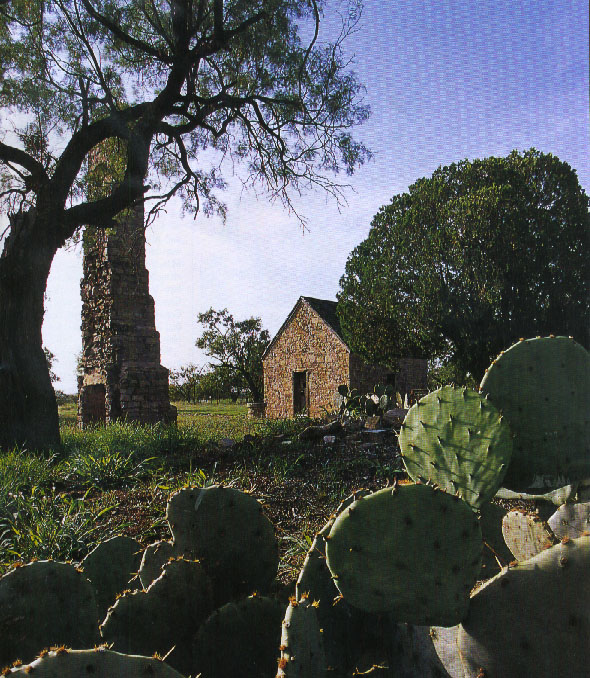

Photo of the restored guardhouse taken by Charles M. Robinson, III from the book, Frontier Forts of Texas.

Life at Fort Phantom Hill had been arduous for the men. The lack of

a post garden, which created a shortage of vegetables in the men's diet,

led to scurvy, intermittent fever, dysentery, colds, and pneumonia.

Nor were necessities provided by settlers in the area, as happened at

most posts, because there were no settlers, and no town had grown up

around the fort. The only break in the monotony of fort life was excursions

into the field, which meant extended marches across arid land with inadequate

supplies of food and water.

Shortages prevailed in all areas of the life of Fort Phantom Hill,

from uniforms to arms. Fortunately the men were not engaged in hostile

action, although it was reported that Indians did visit the post where

they made a general nuisance of themselves. The post did receive a major

scare when Buffalo Hump's tribe of 2,500 passed by the fort. The men

were placed in battle array as son as the Northern Comanche tribe was

spotted. Whether the Indians would have attacked the post is speculative,

for once they saw the preparations, they passed it by with scowls and

angry looks. One arrogant Northern Comanche did send Major Sibley a

message that "when the grass became good again he was coming down

and whip him." (Richardson 1963). The Indian never came.

One final story of interest regarding Fort Phantom Hill deals with

who burned the post. There are three versions of its destruction. One

says that is was burned by trooper Scullion and a slave who slipped

back the first night after abandonment because of their distaste for

the post. A second has the Indians destroying the post, while a third

says that it was destroyed by Confederate troops. All that is known

for sure is that by November 9, 1854 when Charles A. Crosby camped there

it had been burned. (Rister 1938, 9. Richardson 1963, 95).

The withdrawal of the military did not mean the end of occupants of

Fort Phantom hill. In 1858 a Mr. Burlington and his wife operated a

stage station for the Butterfield line until it was abandoned during

the Civil War. After the war Fort Phantom Hill became a subpost of Fort

Griffin. Accordingly, on June 5, 1871, Capt. Theodore Schwan and Company

G of the Eleventh Infantry were sent to Fort Phantom to protect the

traffic through the area, and to provide a detail of one noncommissioned

officer and six men to guard the mail station at Mountain Pass, the

first stop south of Phantom Hill. In 1874, a detachment from the fort

was engaged by a force of seventy-five Comanches and Kiowas. Following

a brief battle of one and a half hours the Indians broke off hostilities,

with six killed and several wounded. (Rister 1938, 11-12).

As hostiles moved further west and thousands of immigrants began to

settle in West Texas the troopers left Phantom, but in their place grew

a thriving frontier town of Phantom Hill, complete with hotel, saloons,

gambling halls, and various shops. When Jones County was created it

was hoped that Phantom would become the county seat, but it lost out

to Anson. It was not long before Phantom was once again abandoned. (Rister

1938).

Today the remains of the fort are located on private land. The owner,

Jerry Eckhart, is doing his best to restore some parts of the post and

to make it a pleasant stop for travelers. It is interesting to note

that Fort Phantom Hill was originally built on land that had been sold

on August 3, 1851, to A.C. Daws for fifty dollars and the only reason

that it did not create a problem was its isolation. The old powder magazine

to the west of the road still stands, as well as the post guard house.

A part of the stone commissary can still be seen on the east side of

the fort, and of course the chimneys still stand like sentries on the

prairie. A poem written by ranch poet Larry Chitenden fully catches

the spirit of Phantom in the first stanza which reads:

On the breezy Texas border, on the prairies far away

Where the antelope is grazing and the Spanish ponies play;

Where the tawny cattle wander through the golden incensed hours,

And the sunlight woos a landscape clothed in royal robes of flowers;

Where the Elm and Clear Fork mingle, as they journey to the sea,

And the night-wind sobs sad stories o'er a wild and lonely lea;

Where of old the dusky savage and the shaggy bison trod,

And the reverent plains are sleeping 'midst drowsy dreams of God;

Where the twilight loves to linger, e'er night's sable robes are cast

'Round grim-ruined, spectral chimneys, telling stories of the past,

There upon an airy mesa, close beside a whispering rill

There to-day you'll find the ruins of Old Fort Phantom Hill.

(Rister 1938, 18)

Communities and Related Links

|