|

Coronado and his conquistadors arrived from Spain in the middle

1500s on stallions in their search for gold. Thus mounted, conquering

a continent void of horses was embarrassingly easy. The one bugaboo

confronting a cavalry on stallions was to lose control when meeting

an opposing force that included mares in heat, and that, of course,

was just not possible in America.

The Spanish, like other European and Asian nations,

had long been victimized by horsebacked barbarians. They didn't intend

for this to reoccur in America, so decades passed before reluctant

authorities nervously granted permission to the colonists in Santa

Fe to teach their Pueblo-Hopi slaves the equestrian skills necessary

to ride herd on the breeding stock. Apparently some of these new vacqueros

deserted, taking horses, bridles and saddles to Apache camps. Spanish

records reported the first mounted Apache attacks in 1650, eventually

resulting in a Pueblo-Hopi uprising and the Spaniards' decade-long

abandonment of their New Mexican rancheros.

In the early 1700s, knowledge of the horse had spread

to Indians throughout America. The Comanches were among many tribes who

roamed into the Taos/Santa Fe area in search of horses. They revered

the horse and when first encountered they thought it was a wonderful,

large dog. Like Romans, the tribe related mythologically to the wolf

and were kind and playful, packlike. Comanches'

exceptional skills at horse riding, stealing and breeding eventually

enabled them to expand their herds until they dominated the Southern

Plains. They became the role models to the other thirty or so tribes

that adopted the nomadic horsebacked life of the raid and the hunt.

Their fighting

abilities on horseback soon earned them fearful respect throughout

the southwest. In one of their earliest raids they stole a herd of

over fifteen hundred. Their herds swelled to tens then hundreds of

thousands. Soon no respectable chief would have less than a few thousand

horses, and it wasn't that uncommon for any warrior to own over a thousand.

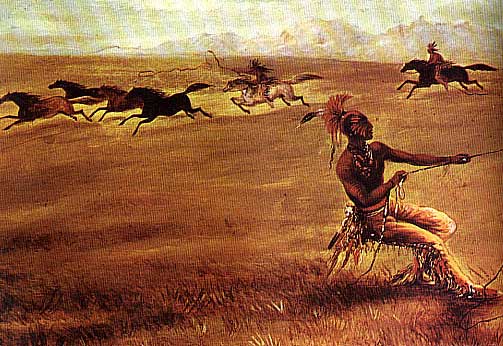

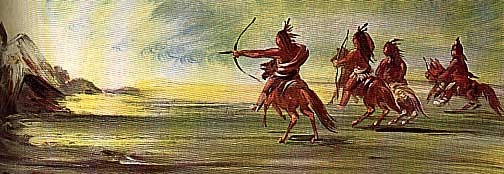

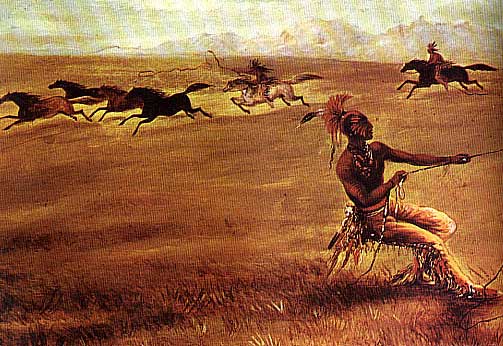

Painting by Alfred Jacob Miller

Subject was Sioux warrior demonstrating Comanche riding technique.

As possession of horses became a signifier of status, Comanche men loathed walking anywhere. When a warrior

desired to go somewhere, a wife brought his horse right to his teepee's

entrance. Boys were placed on horseback before they could walk, and

they could catch and saddle their own ponies by the time they were five.

Colonel Dodge observed, some years after his 1833 encounter with a large band of Comanche in the Wichita Mountains, that "the Comanche were not only the best horse thieves, but the best horse breeders in America." The band treated Dodge and his dragoons in an aloof and indifferent manner but they showed an acute interest in the army's heavy horses. They preferred paints and emphasized strains that would produce better traveling, hunting or war ponies. The Comanche didn't steal Dodge's horses though the heavy strain would surely breed in distance and comfort. They learned through a century of dealing with foreign nations that new generals and their armies would soon return with horses and weapons as tribute for an alliance.

Comanches parents were exceptionally kind and loving to their children.

So tenderhearted in fact that grandfathers or uncles assumed the responsibility

for the young boy's rigorous martial training. Some legends proclaim

that the most promising young warriors attended leadership school.

A woman served as commandant at a camp established for this purpose

and prominent war chiefs visited, lecturing the boys on weapons, communications

and tactics. Texas Ranger Noah Smithwick was appointed Texas Comanche

agent and spent a considerable amount of time living with the tribe

in the late 1830s. He noted the boys were constantly engaged in contests

that developed their riding, hunting and fighting skills. Simulating a hunt, young warriors

would sometimes pursue a young buffalo bull.

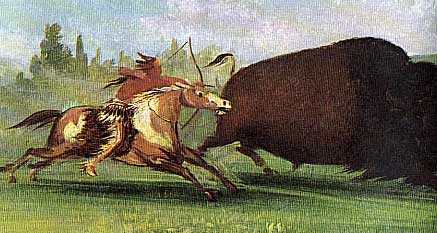

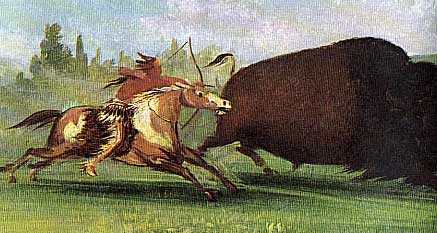

The following description is from the book Los Comanches, The Horse People, 1751-1845, by Stanley Noyes.

"The hunters would begin by shooting arrows

into the animal's hump. When it became infuriated and charged one

of them, another would gallop beside it and jerk an arrow from its

hump. At the fresh pain the bull would turn and attack its new tormentor.

It was then that a well-trained horse was essential. Smithwick recorded

seeing old bulls whirl so quickly that it was 'all the Indian's

pony could do to get out of the way.' But then another warrior

would race in and snatch an arrow, and the bull would turn on him.

The hunters would keep this up until the animal was exhausted, when

they would dispatch it and retrieve their arrows."

Young warriors also played a variety of games involving

racing, dismounting and retrieving each other but roping skills were

most valuable when it came to capturing horses.

Just as horses trained for the hunt knew to turn away

at the sound of a bow twang to avoid possible goring, war ponies were

trained to respond to the lightest touch of the knee or foot. The

warriors tied a rope around the horse's neck with a loop on the opposite

end which held his ankle. On approaching the enemy, the Comanche could

lean over the side of his horse at a full run, firing from underneath

the horse's neck while using the animal's body as a shield. These

skills gave the Comanche a tremendous advantage on the battlefield,

forcing their opponents to take a defensive position and dismount

in order to fire accurately. Contrary to the movies, only the Comanche

tribe attacked on horseback in battle.

Buffalo Hunt by Horseback

The average mounted Comanche warrior could circle a

modern-day football field at a full run while accurately shooting

twenty arrows at targets on the opposite side of the field, and this

was done in the time it took to reload a gun. They usually attacked

in concurrent circles of five to eight warriors. The circles were

coordinated through a complicated communication system involving oral

commands as well as hand and mirror signals. They swarmed their enemy,

alternating between arrows, lances and short arms (guns, swords, and

tomahawks) depending on the range.

The Comanche needed markets to sell stolen horses and captives. In early 1720 when they found they were unwelcome at the trade

fair at Taos, they took this opportunity to show the New Mexicans

their version of a hard bargain. They grabbed a number of local citizens,

and in plain view of their former trading partners began torturing

and killing. Every cry drove home their bargaining points until their "shopping" privileges were reestablished. The tribe recognized

the value of terror and took every opportunity to exhibit cruelty,

establishing fear in the hearts of their opponents.

As the power and influence of the Comanche rapidly increased, they were not content

to take away the Apaches brief control of the Plains horse trade. The Comanches doggedly pursued their enemy, eventually resulting in

the 1750s attack on the Spanish mission at San Saba, which had become

a sanctuary to the Lipan Apache.

The massacre at their little outlying mission

caused the Spanish to retaliate with a punitive force of five hundred.

The army marched to the Red River where they found the Old

Spanish Fort defended by more than a thousand Comanche and Wichita

warriors, as well as French soldiers. The Spanish troops were easily

routed, abandoning much of their armor and weapons, including two

cannons, in their panicked retreat down the Grand Prairie toward their

barracks in San Antonio. The Spanish realized they had waited too

long to conquer the Plains and resigned to farming and tending their

herds under armed guards in their South Texas colonies.

Through the next century, the Comanches effectively

owned the hunting grounds, fields and people abutting their buffalo

range. Their serfs were expected to provide them with gifts and supplies,

including manpower in time of war.

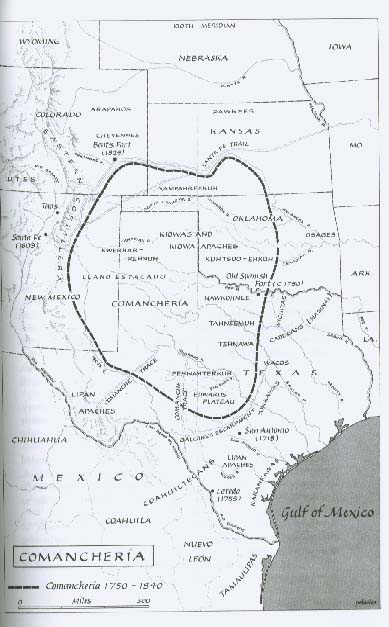

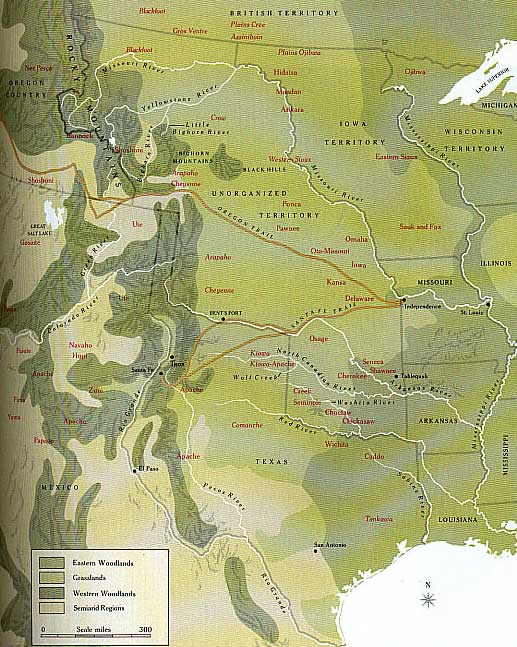

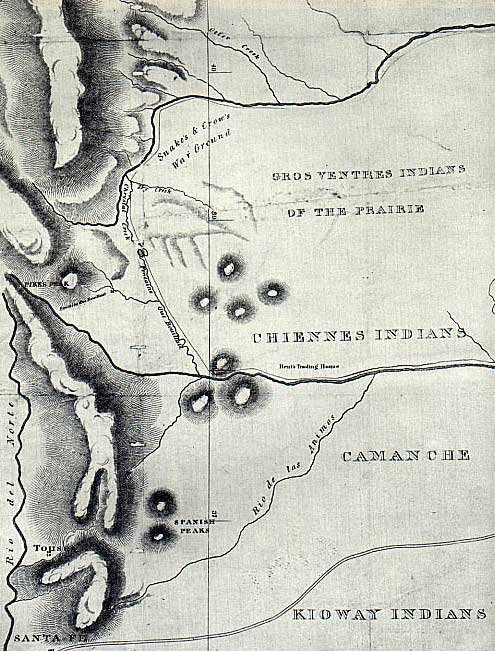

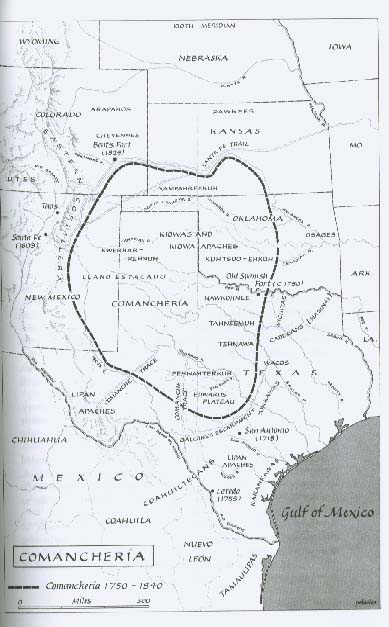

By 1725, Most of those lands east of the Southern Rockies that the Spaniards had called Apacheria had become Comancheria, the domain of the Comanches. The terrible, buffalo-horned warriors on horseback had seized an enormous new empire. This territory was comprised of all the lands between the Spanish frontier and the Arkansas River, lying between the Grand Cordillera and the Cross Timbers of Texas. Its core covered six hundred miles from north to south, four hundred miles from east to west, lying entirely on the southern portions of the Great Plains from the ninety-eighth meridian to the foothills of the Rockies.

…The infrequent rivers-The Arkansas, Cimarron, Canadian, Washita, Red, Pease, Brazos, Colorado, Pecos and their canyons, and the more frequent springs in the arroyos, made fertile oasis. They gave life to great cottonwood trees, and their sandy banks were covered with wild plums and mustang grapevines. To the east, downstream, appeared thickening strands of pecans and walnuts, interspersed with ash, elm, chinaberry, hackberry, bois d'arc or Osage orange, willows, and oaks. Redbud and haws and persimmon bushes sprouted. The land was not barren anywhere; even in the driest portions, clumps of mesquite struggled to suck sustenance from the soil.

The proof of richness was the teeming wildlife, the greatest concentration of animals on the North American continent.

Coronado found the Llano Estacado swarming with buffalo, in “numbers impossible to estimate,” as he wrote to his king. The Spanish, disillusioned at not finding the Seven Cities of Cibola on the plains, named the native herbivores cibolos. Some Spaniards guessed that individual herds numbered in the millions. There were also hundreds of thousands of pronghorn antelope, bear, cats and great elk in the canyons. There were peccaries and hares and rabbits and, soon, wild horses, with wolves and coyotes to prey upon them. The high plateaus of Texas lacked the variety of animals in Africa, but because the great predators were fewer, these grasslands held more game.

Picture of Comanche with Wild Horses

In this vast territory, Comanches found everything they required for their way of life. The grazing beasts provided meat, horns and hides. The river banks offered wood, forage and fruits, nuts and berries, food and raw materials. The bears gave up fat, fur, and sinews. The canyon brakes made superb, protected camp sites.

The winter blizzards were passing things. Here, the sun shone in all seasons. The deep winter months were seldom hungry ones, as so often in the north, for the bison massed on the southern ranges in cold weather. The Comanches had found, and seized, a natural hunter’s paradise for horse Amerindians. Compared to most Amerindian peoples, they were now highly secure upon their new territories. Their vast striking range, new and fearsome reputation, made all other tribes give Comancheria a wide berth. Buffalo-hungry Caddoans in the east and starving Apaches and Tonkawas in the south rarely dared to venture onto the Comanche range.

The above story is from the book, Comanches, The Destruction of a People, by T.R. Fehrenbach.

In the late 1700s, increased westward migration across

the Mississippi and a show of strength by the Spanish military in

Santa Fe compelled the Comanches to make treaties first with the

governor of Santa Fe and then with the Kiowas. These alliances provided

the Comanche with a dependable market to the west and a strong buffer

to the north. Their powerful hold on the Southern Plains was even

stronger a century and a half later when Texas became a Republic

and white settlements began to sprout up along the middle Colorado

and Brazos rivers.

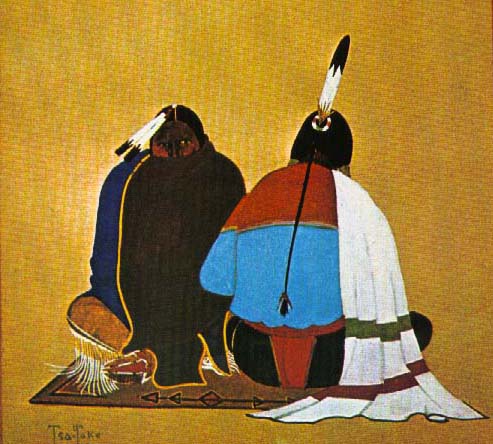

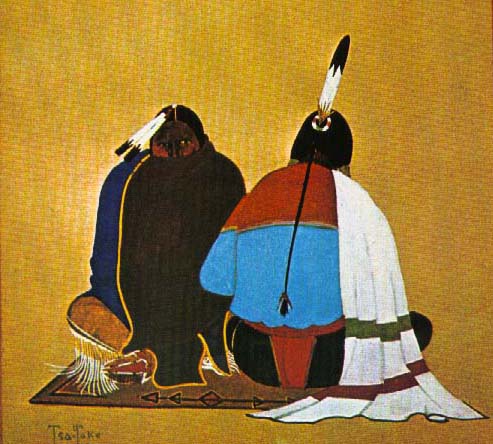

Kiowa/Comanche Painting by Monroe Tsa-Tok

Kiowa/Comanche Painting by Monroe Tsa-Tok

Their alliance with the Kiowas resulted from a meeting in 1806 described by Stanley Noyes, Los Comanches, The Horse People 1751-1845.

In 1806, the Comanches participated in an event

of great consequence to them. The event is recorded in a story passed

down from one generation to the next among the Kiowas; their tradition

has it that two separate parties of Comanches and Kiowas, enemies

at that time, arrived at the house of a New Mexican, possibly a

comanchero, who was on good terms with both peoples. This nuevomexicano

was able to arrange a parley between the hostile groups of warriors.

During the talk, a Comanche chief, Pareiya (Afraid-of-Water), invited

a Kiowa chief, Gui-k'-ati (Wolf-Lying-Down), to return with him

to his camp and spend the summer there. During that time they could

talk about peace between the two peoples. Wolf-Lying-Down, the second

most important Kiowa in the tribe, accepted the invitation. But

he told his braves to return to the trader's house when the leaves

turned yellow. If he were not there, the Kiowas were to avenge his

murder.

The party of Kiowas left. Wolf-Lying-Down rode off

with Afraid-of-Water and his warriors. They traveled south of Pareiya's

camp on the Brazos River, where the Kiowa spent the summer among

the Comanches. The People entertained him as a guest. That fall

Wolf-Lying-Down met his warriors, as agreed upon, at the trader's

house, and there was peace between the tribes.

Comanches Drying Meat

There were certain aspects of the Kiowa that the Comanches surely envied and admired. The Comanches came to the Southern Plains as roaming

hunters, whereas the Kiowa had been there for over a thousand years,

and they developed a rich culture that yielded an accurate calendar, making

them wealthy farmers. To their credit, at least in the Comanches' eyes,

they abandoned their ancestral corn fields for the nomadic life of

the hunt and the raid. They had developed pictorial writing, which

enabled them to accurately record and pass down accounts of successful battles,

treachery of their enemies and perhaps most appreciated by the Comanche,

stories of revenge achieved through insidiously elaborate tortures

and murders.

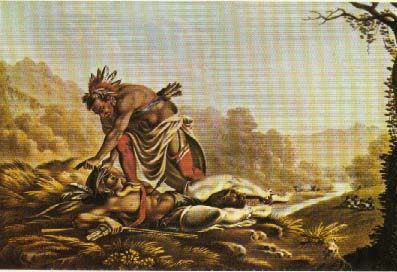

Torture and Mutilation

The following story is from the book, Comanches, The Destruction of a People, by T.R. Fehrenbach.

The protracted rape, humiliation, and murder of female captives began on the homeward journey, leaving a bloody trail behind the war party. This began when the warriors believed they had put enough distance behind them for security, and they could make a camp and light fires. There was no taboo against tormenting women, but this rarely went beyond sexual assault, though Amerindians were known to impale women on rough-cut stakes, or cut their heel tendons and leave them in the wilderness. Purely sexual sadism seems to have been almost unknown, because there was little sexual frustration to feed it. More often than not, the captive female brought back to camp had more to fear from the jealousy of the Nermernuh women, who heaped abuse and even physical punishment on them.

If there were male prisoners, the normal practice was to try to bring them back for the pleasure of the women. When this was impractical, they were killed on the trail. Since bravery was the supreme virtue among Amerindians, torture was the supreme test. The tormentors got the same psychic satisfaction from breaking a victim's spirit while they destroyed his nerves and body as they derived from mutilating the dead. However, because valor was so respected in this war culture, the tortured captive who died bravely gained honor even in the eyes of enemies, a nicety most European minds failed to grasp. The victim who was defiant to the last even won a sort of triumph: he made bad magic for his killers. There is one documented case of a nameless white man on the plains who laughed in the faces of his Nermernuh captors with complete coolness as they graphically threatened his genitals with fire and steel. Abashed, a war chief ordered him released unharmed, as having a magic too powerful to challenge.

A Spanish-recorded description of the mass torture of a number of captured Tonkawas is enough to show why the subject of torture was always close to the minds of whites on the Amerindian frontier. In this case, the Nermernuh warriors staked out their victims, and began applying fire to each captive's hands and feet until the nerves had been destroyed in each extremity. Then, they amputated the ruined extremities and began the fire torture again against the sensitive, bleeding flesh. All of the victims were scalped alive, so that they would know the full extent of their degradation. Finally, tiring of the business, the Nermernuh tore out the Tonkawas' tongues to silence their cries, and heaped the writhing victims' scrota and bellies with blazing coals. The Nermernuh then went to sleep around the torture fire.

Even worse fates could befall warriors brought back alive to Nermernuh encampments. Here, especially once the victim's screams established that his medicine was broken, the work was left to the women. Most observers reported that the women were far more patient and vicious tormentors than the males. It may have been the exercise of vengeance against their lot in life, but at any rate, the females destroyed the captive by the most drawn-out and hideous means they could devise. They cut off his fingers and peeled his eyes; they stretched his tongue and charred his soles, and they invariably devoted fiendish attention to his penis and testicles. The torture went on for hours, even days, so long as the body survived.

Meanwhile, if the war party had come back with glory and with captives and booty-and without losses-the whole band erupted in frenzied celebration. Warriors recounted their deeds to the thump of drums and the admiring whoops of women. Great men honored others and themselves. Coups were claimed, and reputations established-or destroyed. The returned warriors then danced themselves into exhaustion while their bloody trophies hung drying on the scalp poles.

If the war party came back reporting disaster or with any dead, the hysteria was reversed. Lamentation swelled through the night, and might go on for days. Bereaved families mourned for months; women cut their breasts and severed fingers in despair. Councils and puhakut sought medicine for revenge. And thus the cycle would go on, war and reprisal without end.

From the book, Los Comanches, The Horse People 1751-1845, by Stanley Noyes:

Comanches put the prisoner to work digging a hole, telling him they needed it for a religious ceremony. When the captive, using a knife and his hands, had completed digging a pit about five feet deep, they bound him with rope, placed him in it, filled the hole with dirt, packing it around his body and exposed head. They then scalped him and cut off his ears, nose, lips, and eyelids. Leaving him bleeding, they rode away, counting on the sun and insects to finish their work for them. Later, back at their encampment, they told the story as an excellent joke, one which gained them a certain celebrity throughout the tribe.

...Back in Spain, the Peninsular War, 1808-14, was partly a guerrilla campaign fought by the Spanish people against the troops of Napoleon. It is called the "War of Independence" there. Although a British and Portuguese army finally drove the French from Spain, the Spanish people in the interim fought courageously-and suffered. Francisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes created a vivid record of their suffering in his series of etchings, Los Desastres de la Guerra. Of these, number 39 offers the naked, mutilated bodies of three men bound to a tree. Their genitals have been cut off. The severed head of one is impaled on a branch, while his arms hang on another. This kind of sight would not have been unfamiliar to the Comanches. Clinton Smith told of seeing the Ietan women of his band occupied on a battlefield by cutting off the arms and legs of the naked enemy dead and hanging them from trees.

Another Goya etching, number 37, is entitled Esto es Peor, or "This is Worse." It depicts another corpse of a naked man, his arm lopped off by the shoulder, seated on a dead tree. On close observation, the viewer sees a sharpened branch entering between his buttocks and protruding from his back, a little below the neck. French soldiers in the background busy themselves with the dead or with killing others. If this image of war as practiced by nineteenth-century Europeans had circulated during a council of Comanche chiefs and warriors around 1820, they would have recognized it as an instance of the kind of war they themselves could bring to their worst enemies. It was the kind of war they would bring, in a couple of decades, to the Anglo-Texans, after they had come to hate them as much as they presently did the Apaches and the Osages.

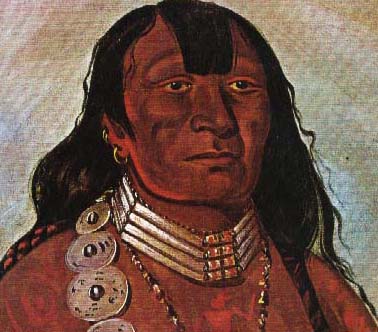

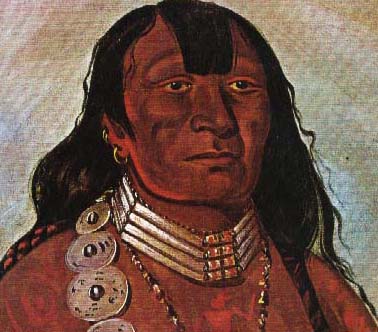

Two Hatchet, Kiowa

Kiowas raided at a greater distance than

any other tribe and probably impressed the Comanche with tales of

Central America's monkeys and parrots. The Kiowa maintained a rigid

warrior society; the most honored entered the brotherhood of the Ten

Bravest. Members wore a long, red sash which they anchored to the

ground with an arrow when fighting became intense. This signified

they would remain until death, encouraging their warriors to renew

their efforts.

In the same spirit as the Kiowas' Ten Bravest, a Comanche motto proclaimed "The brave die young."

Possibly the single remark most revealing of Comanche fervor was

one made by chiefs to Governor de Anza of New Mexico in late 1786

or early 1787, after their treaty and alliance with the Spaniards.

Learning that delegations of Lipan Apaches had been visiting New Mexico

to sue for peace, they begged de Anza not to grant a treaty to this

mutual foe; otherwise, they pleaded, they would have no enemies to

fight and, as a result, would become effeminate.

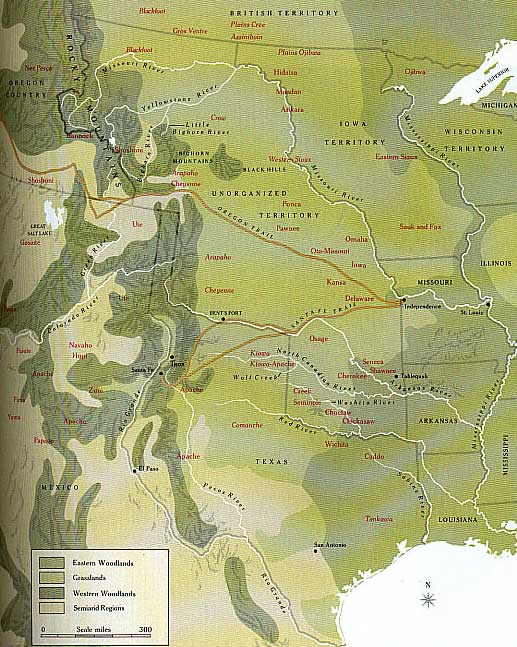

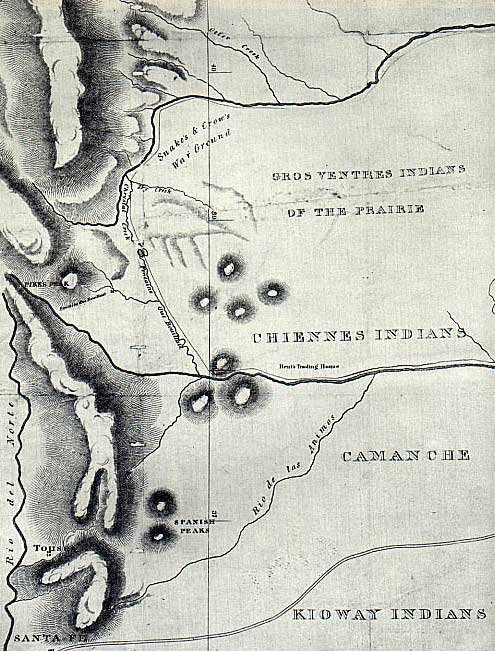

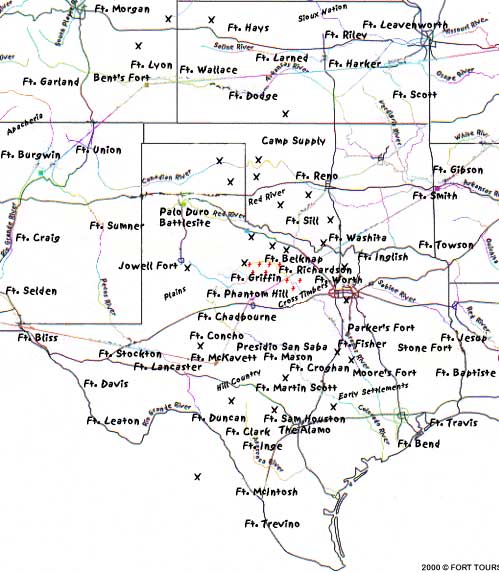

Plains Tribes, 1840 Map

Mounting Comanche battlefield losses, as well as deaths

due to cholera and small pox, once again compelled a new strategic

alliance. This time it was with the Cheyenne and Arapaho, who were

more than agreeable since all shared common enemies including Osage,

Utes and the displaced civilized tribes from the eastern seaboard.

Little Mountain painted by George Catlin in 1834

To establish this alliance, the proud and aloof Comanche chiefs allowed their

gregarious Kiowa allies to host the Great Peace

held at Bent's Fort. The highlight of the event was Master of Ceremony

Little Mountain's presentation of several thousand Comanche/Kiowa

horses. This deed greatly strengthened their former enemies and

was an indication of Comanche confidence in their own superiority.

1840 Plains Tribes Map

The following description of the Great Peace is from the book, Los Comanches,

The Horse People, 1751-1845 by Stanley Noyes:

...the Comanche and Kiowa warriors had been in a

vicious war with the Cheyenne. The Great Peace was called at Bent's

Fort. The allies gave ordinary Cheyenne men and women four to

six horses apiece but reserved the most and the best for the chiefs.

Satank gave the most, about two hundred-fifty head of horses.

The allies gave so many ponies that the Cheyenne and Arapaho didn't

have enough ropes. The next night the Cheyenne threw a feast and

gave the allies brass kettles, blankets, cloth, beads and guns.

Trading agreements were made that lasted as long as the tribes

kept their freedom.

The United States began their effort to establish relations with the Comanche in 1832 when President Jackson sent Sam Houston to San Antonio to invite Comanche leaders to council with the United States at Fort Gibson near modern Muskogee, Oklahoma. Houston urged the Comanches to meet several times through the next year and they readily agreed to the benefits of making peace with the Osage, but they were reluctant to enter the Cross Timbers because it was impossible to maneuver their horses through the terrain. The Comanche wanted all the room they could get because many Osage warriors topped seven feet in height and were considered the fastest runners in North America. Comanches bobbed the tails of their ponies in anticipation of an Osage battle because of the warriors' ability to chase them down and stab them in the back or knock down their horses within a fifty yard sprint.

In 1833, Osage Chief Clermont

led three hundred of his warriors east of the Cross Timbers in the

vicinity of Fort Gibson across the plains to the Wichita Mountains.

They struck a Kiowa camp near present day Fort Sill, killing one hundred

and thirty women, children, and old men; placing some of their heads

in cooking pots to be found by the returning Kiowa hunting party.

Colonel Dodge and his dragoons came to the Wichita Mountains in 1834 to establish peace between the Kiowa/Comanches and U. S. allies and trading partners, the Osage. Kiowa negotiators represented Comanche interest at councils at Fort

Gibson and the resulting treaty lasted over a decade.

The nature of the Comanche was widely commented on by

their opponents during the centuries of warfare. Texas Indian Superintendent

Robert S. Neighbors said in the 1850s "the Comanches had a gay

cast of mind and from the liberality with which they dispose of their

effects" on ceremonial occasions, "it would induce the belief

that they acquire property merely for the purpose of giving it to

others." Decades earlier in New Orleans, the Marques de Rubi

similarly stated that the Comanches and other Indians of the north

were, "because of generosity and gallantry," the "least

unworthy" of the native nations to be the enemies of the Spaniards.

Stephen F. Austin

(Photo from the book, The Men Who Wear The Star, by Charles M. Robinson,

III)

In Los Comanches, The Horse People, 1751-1845 Stanley Noyes makes several references to famous Texans'

opinions of the Comanche:

If the presence of Americans on the eastern frontier

of northern New Spain made Spanish officials increasingly uneasy,

the evidence suggests that the Comanches, on the other hand, held

a largely favorable attitude toward the newcomers. In 1822, for

example, Stephen Austin, "the father of Texas," was traveling

between San Antonio and Mexico City. In Mexican Texas, near the

Nueces River, a war party of fifty Comanches captured him and a

companion. But when the Comanches learned the two men were Americans,

they returned nearly all of their belongings and released them.

That same month, in a letter, Austin interpreted the incident by

noting that the Comanches' "partiality for Americans [was]

explained by their illicit trading relations with certain Americans,"

who were probably operating mainly in the vicinity of Natchitoches.

Also indicative of the People's attitude toward americanos was the

fact that three years later, when Comanches were raiding San Antonio,

they left Austin's little colony alone.

David G. Burnet

In 1824, the Cincinnati Literary Gazette began printing

a series written by future Texas President David G. Burnet about

the Comanche Indians. Young Burnet was not that impressed with the

Comanches he had seen in Texas. He acknowledged the speed of their

ponies and their rider's knowledge of the geography which served

to inspire the warriors with an artificial fearlessness that endowed

them, yet Burnet wrote "all one really had to do was oppose

Comanche warriors with decision and energy and they would crouch

like the spaniel or fly like the stricken fawn." One wonders

if these words haunted him later when each mile advanced into Texas

frontier cost seventeen white lives. Burnet held the Comanche women responsible

for "the largest portion of the nation's barbarity." He

went on to state flatly that they were "infinitely more cruel

and ferocious than the men." Certainly if a sense of injustice, as well as long-endured overwork

and frustration, make for anger and cruelty, most of the women of

the tribe had plenty of motivation to even accounts with the world

in the form of a helpless enemy, especially when that enemy was

a man. They took a "peculiar delight," wrote Burnet, "in torturing the adult male prisoners."

It was Burnet's Texas experiences in 1818 & 1819 that he wrote

about in 1824.

The Sentinel, painted by Frederic Remington in 1908

Local tribes led by Choctaw Tom raided the Colorado

settlements as far south as Bastrop. Whether the Comanche were

drawn in to help their subjugates or simply angered by the new

settlers, Comanche and Kiowa warriors attacked Parker's Fort in

the summer of 1836, beginning their fateful four-decade war with

the Texans.

The following is from the book, The Men Who Wear

the Star, by Charles M. Robinson, III:

In July, 1835, a company of men under Capt. Robert

M. Coleman attacked a Tawakoni village in what is now Limestone

County, east of Waco. Though surprised, the Indians outnumbered

the whites, forcing them to retreat to Parker's

Fort, seat of the Parker clan, some forty miles east of Waco.

Coleman sent for help and was reinforced by three companies under

Col. John H. Moore. The Indians retreated. Moore's Rangers combed

the countryside as far as the present site of Dallas before returning

home. These various skirmishes, insignificant on their own, would

have far-reaching repercussions, not only with the local tribes

but with the powerful Comanches of the Plains.

Congress of Republic of Texas agreed to appoint Noah

Smithwick as commissioner to try and work out an agreement with the

Comanches but they specified that there could be no "fee simple"

right of soil to be acknowledged. The Comanches maintained they would

hold all the country north of the Guadalupe Mountains and would kill

any surveyors that came into their area. Smithwick recalls that he

and Houston eventually "fixed up" a treaty with the five

chiefs but he claimed he didn't recall the terms but emphasized that what

peace it bought only allowed the settlers to resume fighting amongst

themselves. By early 1838 settlers moved into Comanche country and

surveying parties began to probe further west of the settlements.

On August 10th, two hundred Comanches unsuccessfully attacked Colonel

Henry Karnes and twenty-one of his men. On October 20th, another war

party struck surveyors within five miles of San Antonio, killing two

of them and eight residents of the local settlement.

Sketch by painter Henry Arthur McArdle

from the book, Savage Frontier II, by Stephen L. Moore

Following the Council House Fight and several additional

Ranger victories, the exhausted Comanche agreed

to terms with Houston under the Bird's Fort Treaty.

Texas had established trading houses at Waco, Presidio San Saba and

Comanche Peak in 1842. Pragmatic Comanches appreciated the value of

trade over expensive revenge. By 1845, roads west of the Cross Timbers

from Fort Gibson, Fort Smith and the Red River were crowded with wagons

as several thousand settlers per week passed onto the Plains. In the

spring of 1846, the United States Commissioners met with the Comanche

chiefs and negotiated a new treaty to succeed the one of 1835, but

by the Fall gifts promised by the U. S. failed to arrive and hostilities

resumed. The eventuality of the United States' victory was never in

doubt, but the ambitions of the young warriors postponed the inevitable

for nearly thirty years.

Kiowa Warrior

The Civil War gave young Comanche and Kiowa warriors

their last opportunity to inflict vicious punishment on the white

settlements. The victorious Union struggled for years in an effort

to negotiate a peace with the Plains tribes. At one point, the cunning

Kiowa were given the Texas Panhandle and though the 1868 Medicine

Lodge Treaty canceled that deal, the chiefs were given a full

hearing, including Satanta's famous oratory, and such advantageous terms

that for years the tribe continued their raiding practically unmolested

until the 1871 Warren Wagon Train Massacre.

In the first year of the Red River War, 1874, Thomas

Battey, a Quaker school teacher, displayed a gadget called a stereoscope,

with which his Kiowa and Comanche charges could view photographs. First

he showed them mountain landscapes from Colorado familiar to even the young

boys and girls. Then, he showed city scenes including

buildings and trains, which startled the Kiowa chiefs who had not believed

the stories told by their peers who had visited the United States

over the previous decades. Chief Sun Boy cried

"You think they're all lies now? You still think all chiefs who've

been to Washington are fools?"… "Look-see what a mighty,

powerful people they are! We're fools! We don't know anything! We're

just like wolves running wild on the plains!"

Communities and Related Links

|

|

|

Adobe Walls I

|

Adobe Walls II

|

|

Antelope Hills

|

Battle of Little Wichita

(Kiowa)

|

|

Blanco Canyon

|

Lone Wolf's Revenge Raid

(Kiowa)

|

|

Nocona's Raid

|

North Fork of the Red

|

|

Palo Duro Canyon

|

Pease River

|

|

Rush Springs

|

|

|

|

|

Kiowa/Comanche Painting by Monroe Tsa-Tok

Kiowa/Comanche Painting by Monroe Tsa-Tok