The Old Stage Coach of the Plains, painted by

Frederic S. Remington, can be seen at the

Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

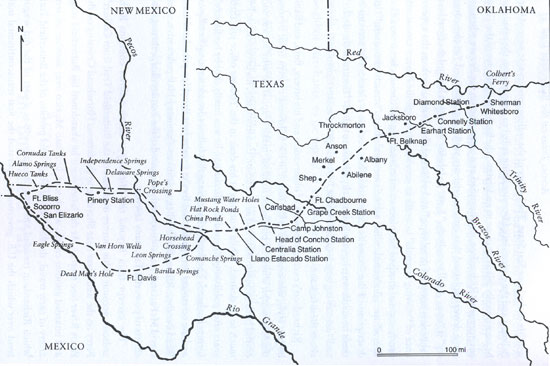

Ty Cashion reports in his A Texas Frontier, in 1857 the postmaster general entertained several bids to deliver mail and carry passengers between Saint Louis and San Francisco. He awarded the coveted prize to the Southern Overland Mail, headed by an upstate New York firm under John Butterfield. Well grounded in finance and communications, Butterfield had been the driving force in consolidating his interests with those of Henry Wells and William G. Fargo to form the American Express Company. His acquaintances included newly elected President James Buchanan, whose political leanings toward the South no doubt influenced the selection of a route favorable to that bloc. The path of the stage road was of paramount importance; most politicians believed that it would presage a Pacific railway.

Many perceived a potential windfall in locating along the route. When Grayson County businessmen learned that the stag would be crossing the Red River a the tiny community of Preston, they built a new road, inducing the stage line to shift its course through the more populous town of Sherman. From there to Belknap, each county followed Grayson's lead, continuing the road, making improvements, and even building bridges.

Albert D. Richardson gives a first-hand account of his 1859 Butterfield Stage ride.

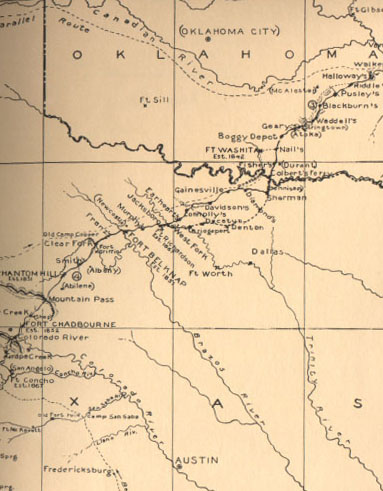

For his stageline, Butterfield's utilization of Captain R.B. Marcy's Southern Route, used to escort gold seekers safely into Indian Territory,

greatly encouraged settlement along the line. Stage stations had to

be built approximately every twenty miles. Buildings were needed to

house his employees and provide dining rooms for stage riders, and corrals

were necessary to hold the livestock. Adequate supplies and water had

to be available. It was an enormous investment for this adventurous

businessman which promised handsome profits and apparently provided

quite a bit of fun.

Butterfield Stage Line,

A Famous Bet

The following excerpt, from the book, Ninety-Four Years In Jack County 1854-1948,

by Ida Lasater Huckabay, describes Butterfield's race against the Great Eastern steamer.

In 1857, the largest steamer in the world, Great Eastern, which was

built in London, was set afloat. It was built by the Eastern Navigating

Company to maintain an ocean route to the East, Australia, and around

Cape Good Hope. It could carry 1,000 passengers, 5,000 tons of merchandise

and 15,000 tons of coal. The propelling power comprised of both sail

and screw. It was 679 feet long, eighty feet amidship with tonnage

of more than 20,000. Being too large for the commerce of that day,

it was never a success. But in 1859, the Great Eastern was the sea

hound of the ocean, the boat talked and boasted of when ships were

mentioned.

The commander of the big liner was Captain Harrison, well known in

the commercial circles in New York. John Butterfield was a popular

New Yorker with an acquaintance from coast to coast. In midsummer

of 1859, John Butterfield and Captain Harrison met at a dinner in

New York City.

John Butterfield was justly proud of his overland stage and never

tired of entertaining the men of the East with the wonders of the

glorious West, his stupendous line of almost 3,000 miles, and the

speed of the horses and mules. Butterfield led the conversation around

to his line and the Texas mules. He elaborated on the mules-there

was nothing to equal them. Captain Harrison pompously smoked and listened,

but mule talk and mule speed grew tiresome to the captain of a 20,000

ton steamer, and after moments of endurance, the captain ventured

that his vessel could go all around South America and beat the mules

to San Francisco. Butterfield was quick with, "I'll bet you can't."

"What will you bet?" asked the captain between puffs of

smoke.

"One hundred thousand dollars," cried Butterfield with

a bang on his fist on the table.

The guests burst into laughter and a storm of questions. With much

hilarity and joking they demanded that the wager stand. Captain Harrison

was more than willing. There was nothing afloat to equal his Great

Eastern and surely there was nothing afoot. Butterfield was likewise

sincere and assured. He would stake his own fortune on his Texas mules.

He requested three months for preparation. This was agreed upon as

official permission was needed from the steam company.

It is said Butterfield spent $ 50,000 in new equipment and practically

all of three months in preparation. New coaches were purchased to

be held in readiness at many points along the route. The drivers selected

were experienced teamsters, and only the fastest span of mules and

teams of horses were held at the change stations.

The Great Eastern, in perfect running order with a selected crew,

its alert captain and passengers, and cargo, steamed out of New York

harbor and turned south. The captain had marked the shortest course.

The vessel was to take the rough and calm seas alike, not a knot was

to be lost. Every man was trained; everyone felt a personal interest

in the boat. The great liner could spread 7,000 yards of sail and

her eight engines could turn out 11,000 horse power. On and on she

sailed, around Cape Horn, up the Pacific, and on the last leg of her

journey

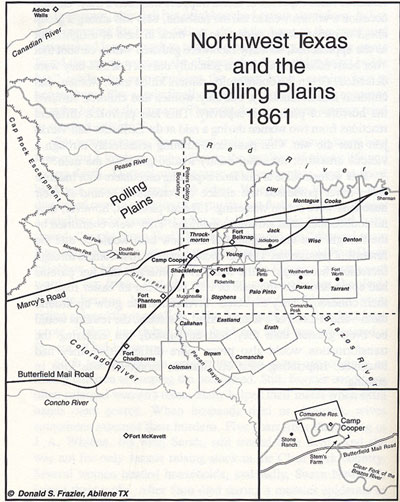

Map from the book, Texas, The Dark Corner of the Confederacy,

by B.P. Gallaway

Over the prairies and desert sped the Texas mules. There was more interest and excitement in the overland run. The steamer ran along on the water, but on land there were bursts of cheers every ten or twenty miles. As the first faint cloud of dust told that the stage was coming, the population began its ovation. It increased as the stage grew nearer and the little change stations became one wild melee of noise, dust, sweating and plunging horse flesh. Each little station stood in readiness with a fresh driver and fresh teams. Before the horses had scarcely stopped, they were unfastened from the traces; others plunging were held in check just long enough to be fastened. The driver threw the mail from one boot of a stage to another. If it was at the station where coaches were changed there was only a slacking of speed.

The excitement reached its climax as the stage started its dash from

each station. Yells and cheers followed the rocking stage as long

as it was visible in the cloud of dust. The mules seemed to have almost

a sportive attitude. On other trips they might have had to be urged,

on the Butterfield race they were held in check. The stage swayed

and bumped but miraculously it kept itself righted. The frontier had

never known such excitement; it far exceeded Indian raids. Side bets

and side interest almost equaled that of the participants; the gaming

thrilled from coast to coast with the race.

Twenty days of travel, of changing horses and mules, wild driving

through the vastness by teamsters who thought only of the safety of

the mails and the station next to be reached. Twenty days and the

last relay dashed into the San Francisco station. The ovation there

was led by John Butterfield. Thirty-six hours later the Great Eastern

docked. John Butterfield and his mules had won.

Comment from a visitor to our site:

I was doing a little looking around for Butterfield info to send a friend. Ran across your page,

http://www.forttours.com/pages/butter.asp which by the way, I love reading your site. Its in that light that I offer the following criticism.

I had never heard the story of the race vs the steamship. Did a little more reading on it and can’t find it anywhere else except yours other’s references to the 80 years in Jack County book. It doesn’t look like the Great Eastern was even in service until 1860.

Nothing in any of the histories for it mention a race to San Francisco or that it even sailed to San Francisco, ever.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Great_Eastern

She was finally launched —after many technical difficulties— on January 31, 1858. She was 692 feet (211 m) long, 83 feet (25 m) wide, with a draft of 20 ft (6.1 m) unloaded and 30 ft (9.1 m) fully laden, and displaced 32,000 tons fully loaded. In comparison, SS Persia, launched in 1856, was 390 feet (119 m) long with a 45 foot (14 m) beam. She was at first named the SS Leviathan, but her high building and launching costs ruined the Eastern Steam Navigation Company and so she lay unfinished for a year before being sold to the Great Eastern Ship Company and finally renamed SS Great Eastern. It was decided she would be more profitable on the Southampton–New York run, and outfitted accordingly. Her eleven-day maiden voyage began on June 17, 1860, with 35 paying passengers, 8 company "dead heads" and 418 crew.

Timeline of the Ship

http://www.julesverne.ca/greateastern.html

Of course, one shouldn’t view those sites either as ultimate resources,

but I can’t find anything about the Great Eastern or any other steamship racing the Butterfield.

I love good stories, but I love good true stories better. . . .

Keep up the good work. Thanks for sharing you time and interest with the rest of us. Brandon Polk

|