Some of the Indians who withdrew from the Lyman fight had found

another target a few miles away, as they headed south toward Palo

Duro Canyon.

Billy Dixon

In the early dawn of September 12, 1874, a group of six white

men riding northeast approached the Washita River on their way

to Camp Supply with dispatches from Col. Miles. Two nights previously

Miles, from his camp on McClellan Creek, five miles north of present-day

McLean, Texas, had sent two noted Army scouts, Billy Dixon and

Amos Chapman, with four enlisted men, Sgt. Woodhall and Privates

Rath, Harrington, and Smith, to report on the continued absence

of the wagon train of supplies under Lyman's guard.

The six men were riding hard to find a place to hide for the

day, as they were traveling at night to avoid Indians on the warpath

in the Panhandle. Suddenly the small group found themselves surrounded

by approximately 125 mounted Kiowa and Comanches warriors.

There was no shelter anywhere, not even a patch of weeds, as

the whole prairie had been burned off a few days before by Indians

retreating from Lt. Baldwin. The couriers' horses were tired from

all-night riding; so a mounted conflict was out. The worst danger

would be in becoming separated so that the Indians could pick

them off one by one. They must dismount and make a stand for their

lives, though it looked futile.

Pvt. Smith, while taking charge of their six horses, was shot

down in the first minutes of the fight. The horses stampeded,

taking with them canteens, haversacks, blankets and coats. Thirty

minutes later every member of the small company had been struck,

one mortally and three others severely wounded.

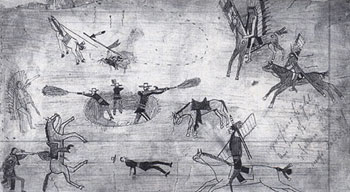

With odds of 25 to 1 in their favor,the Indians were sure of

victory; so, instead of killing the trapped men and moving on,

they indulged in a game of cat and mouse. Circling their victims

on horseback and firing on a dead run, they prolonged the early

stages of the fight. After a while they desisted and rode away

a short distance to watch.

With this first breathing spell, the five remaining men began

looking around for cover. A mesquite flat several hundred yards

away was the best place, but they realized they would never make

it that far alive. Amos Chapman was down with the bone of his

left knee shattered, Smith was apparently dead on the prairie,

and Billy Dixon had received one wound, a bullet in the calf of

his leg which did not disable him.

It was Dixon who spotted a slight depression several yards away,

a buffalo wallow (where the animals had pawed and rolled around

to escape the summer heat). It was about 10 feet in diameter and

shallow, but it was their only hope for any kind of protection.

One by one the desperate men made a run for the buffalo wallow,

with arrows and bullets whizzing all around, until by noon all

except Smith and Chapman were safely there. As each one dived

into the depression, he started digging furiously with his butcher

knife and his hands to throw up the dirt higher around the perimeter

of the circle, and at the same time to deepen the hole in which

they must crouch. The digging went fast because of the sandy loam,

but was, of necessity, interspersed with firing at the Indians

in order to keep them at a distance. Dixon, a former buffalo hunter,

was renowned for his accuracy with a rifle (Battle of Adobe Walls),

and Indians fell with regularity.

Chapman, too, was a crack shot,but was unable to run for the

wallow because of his wounded knee. His exposed position on the

prairie inhibited his firing to some extent. Dixon , as recorded

in his book, tried several times to run to Chapman but was forced

back each time by a volley of bullets. At last, early in the afternoon,

Dixon said, he made it to Chapman and, using all his ebbing strength,

carried him back through a rain of gunfire to the wallow.

Smith's body still lay face down on the parched ground, but they

decided not to risk lives to bring him in. His gun, lying in the

open some distance from his body, was never captured by an Indian.

If one approached it, he was immediately show down from the wallow.

The Indians, proud of their horsemanship, "circled round

us or dashed past, yelling and cutting all kinds of capers."

They knew Chapman well, since he had lived with the Indians and

had married an Indian woman. He was the "squaw man"

who had warned Harnahan at Adobe Walls of the impending Indian

attack. Frequently the warriors called out to him as they rode

past, "Amos, Amos, we got you now." Occasionally a small

group charged straight at the wallow, spears poised, but each

time the leader was brought down.

The afternoon wore on, and the hot September sun bore down on

the man in the buffalo wallow. Every man was suffering from thirst,

since their water supply had been lost with the horses and, according

to Dixon, "In the stress and excitement of such an encounter,

even a man who is not wounded grows painfully thirsty, and his

tongue and lips are soon as dry as a whetstone." Having overcome

their earlier anxiety and turmoil, they were not "perfectly

cool," each man sitting upright in the wallow to conceal

their crippled condition from the Indians.

They had shot nearly all of their cartridges away and the Indians,

venturing closer at every opening, would soon discover their plight

and overwhelm them in a great howl of victory. Realizing the fate

of live captives in the hands of the Indians, their only thought

in the apparently hopeless situation was to fight to their last

breath. That their steady aim was effective was attested to by

the increasing number of dead horses scattered in a ring of death

around them.

By mid afternoon the parched men were so weak from loss of blood

that they could scarcely move. Their thirst was all-consuming,

but still they sat erect, answering bullet for bullet, but hopefully

watching dark clouds approaching from the north.

Just as it seemed that all was lost, that same rainstorm which

had just drenched Lyman's battlefield less than 10n miles across

the Washita now swept over this one. Lightning and thunder dramatized

their salvation, and torrents of cool rain fell upon them. The

rain gathered quickly in their 6-foot square hole, and the men

gratefully slaked their thirst on the muddy water, colored by

blood from their wounds.

Typical of Panhandle weather was the sudden change which followed.

From sweltering heat, the afternoon changed to a sharp cold as

the strong wind shifted to the north. The Indians, who disliked

cold and rain, retreated out of range, drew their blankets tightly

around them, and sat huddled on their ponies. Cold water deepened

in the wallow, and the five hungry, wounded men shivered and ached

as they took stock of their situation.

Ammunition was their immediate concern. Private Rath, taking

advantage of the Indians inattention, ran to Smith's side on the

flat to salvage his rifle, revolver, and ammunition belt. To his

surprise he found Smith still alive. With Dixon's help he managed

to bring the private into their makeshift fortress, where they

realized that a bullet through his lungs had made a mortal wound.

Nevertheless, Smith was propped in an upright position to conceal

how bad his condition was.

At sundown the Indians, cold and wet, disappeared. Dixon and

Rath gathered tumbleweeds brought in by the stiff wind, crushed

them, and made a bed of sorts in the wallow to shield the men

from the damp ground.

In the long, dreadful night of September 12, 1874, Smith, who

in his agony had begged his companions to kill him, quietly died.

The survivors lifted his body outside on the mesquite grass stubble.

Private Rath left the wallow in the dark of night to seek help,

but couldn't find Miles' trail' so he returned in two hours.

The next morning, September 13, was clear and warm without an

Indian in sight. Dixon volunteered to go for help and left the

tattered and crippled group almost defenseless in the wallow.

Within a mile he struck Miles' back trail and soon spotted a large

military outfit in the distance. He attracted its attention by

firing his gun twice. The column turned out to be Maj. Price with

four companies of the Eighth Cavalry from New Mexico, about 225

men in all. Undoubtedly, Price's appearance in the vicinity had

frightened the Indians away from the buffalo wallow as well as

from Lyman's wagons.

Price followed Dixon back to the wallow, but did little to relive

the miserable men, according to Dixon. His surgeon made a brief

examination; the five surviving men needed an ambulance, and Price

had none. Some of Price's soldiers tossed them buffalo meat which

they ate raw, and the major sent a courier to Miles with the news.

Then he moved on. The hapless five men endured another day of

uncertainty and pain in the wallow. Price later explained that

he was in need of supplies himself and was hunting his wagons

at the time Dixon contacted him. His independent command ended

four days later when Price's force was assigned to Col. Miles'

command.

It was midnight of that day, September 18, 1874, before aid came

from Miles and the wounded men received proper medical attention

and food. (That same night Lyman's wagon train across the Washita

was rescued by troops from Camp Supply and also joined Miles the

next day).

At that time George Smith's body was wrapped in an army blanket

and buried in the buffalo wallow, where it has remained since.

The wounded men were sent to Camp Supply for treatment. Amos Chapman's

leg was amputated above the knee. The others recovered and continued

with the Army.