|

||||||

|

|

Early July of 2006, I investigated the progress of the park and trails at Bird's Fort and can report it is exciting. The bridge and display above seem to be only part of a bigger plan that probably is being overseen by Texas Parks and Wildlife.

The following is an essay by Dallas historian Gerald Harris, who, along with a group of his colleagues, are spearheading an effort to establish a hiking/bicycle trail through the original site of Bird's Fort.

View from Bird's Fort Location

Photo courtesy of Gerald Harris

Why Fort Bird (therefore also Grapevine Springs) is Important to Dallas, by Gerald Harris:

Neely Bryan (as his friends and acquaintances called him) first visited his bluff overlooking the Trinity Three Forks in 1839 when there were a lot of Indians in the area. He went back to Van Buren, Ark where he is listed in the 1840 Crawford County Census. When he returned to his bluff in November 1841, it was with the intent of opening a post for trading with the Indians but found none so only then he started thinking about laying out a city, a process in which he had some form of contact in Van Buren.

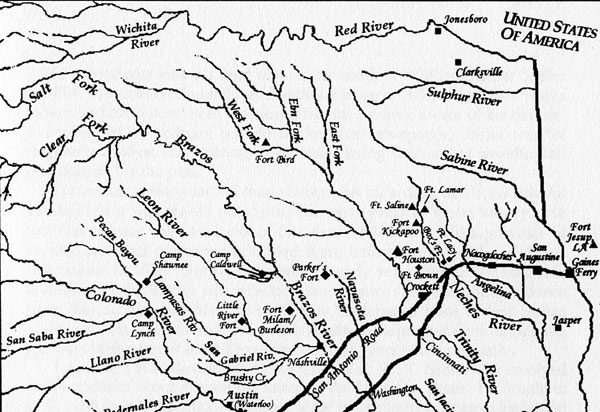

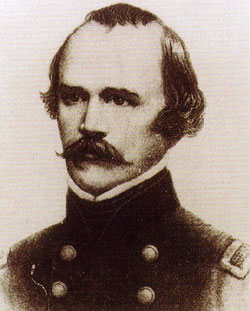

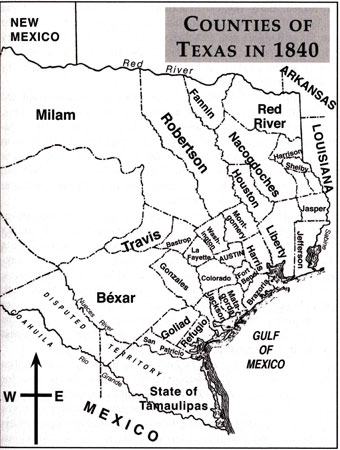

What happened to the Indians was Fort Bird. Prior to the Village Creek Battle on May 24, 1841 in what is now part of the boundary between Arlington and Fort Worth, the Village Creek Valley was home to the largest concentration of Native Americans in Texas. In two prior punitive expeditions in 1938, Texas Militia failed to locate the villages. In 1841, Gen. Edward H. Tarrant and his Militia captured a lone Indian who revealed the exact locations of the Village Creek settlements. The next day, the Militia galloped into the southernmost village with little opposition and burned 225 lodges because the warriors were out hunting. Captain John B Denton took some men and continued up the creek until they ran into opposition and Captain Denton was killed and the Texans were routed. Tarrant learned from prisoners that the villages along the creek were home to over 1,000 warriors so he quickly withdrew. In July 1841 Tarrant returned with 400 men but found the villages deserted. Regrettably, the Indians at Village Creek were peaceful Caddos, Cherokees (among whom both Houston and Bryan and lived), and Tonkawas. While they might not have been totally innocent, they were generally peaceful farmers and hunters and might have made great trading partners with Neely Bryan. The troublesome Comanches and Lipans were further west.

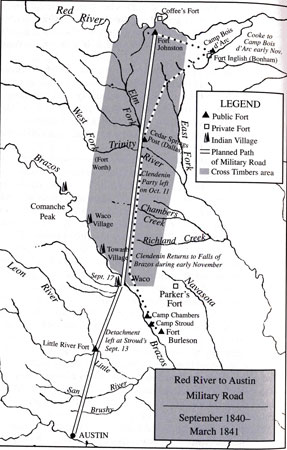

After the May battle, Tarrant ordered the construction and garrisoning of a fort near the site to protect the extreme northwest corner of the Texas frontier. A good defensive position was found with a crescent lake protecting the front (which faced the Village Creek area) and both sides leaving an open opportunity to retreat to Fort Inglish (Bonham), the nearest settlement toward the Red River. Maj. Jonathan Bird and a hundred volunteers of the Fourth Brigade of Texas Militia built and occupied the fort by September of 1841 thus preventing Neely Bryan from having any Indians to trade with; so, instead, he hired an experienced surveyor, J. P. Dumas, to lay out the town and he named it for his friend, Dallas. A promoter, Neely gave lots to early people who would promise to stay and build a town. In the spring of 1842, Neely went to Fort Bird and persuaded several families and some single men to move to his bluff. The group included his future wife, Margaret Beeman. In Feb. 1843, Neely and Margaret traveled four days each way to be married at Fort Inglish.

<Side note: We received this e-mail from a visitor to our site: I was reading the information on bird fort. Very informative but according to my 1901 Texas history book Sam Houstons wife Margaret last name was not Margaret Beeman it was Miss Margaret Moffett Lea of Alabama. And I do know he live among the Indians but will have to check that he was married to one. Just thought I would pass this information along. My information was found in a book called Texas History Stories published in 1901 by the johnson publishing company in Richmond VA. Mike>

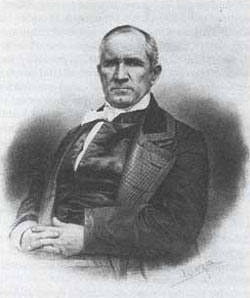

Under the Texas Constitution, the president served for 3 years and could not succeed himself. The 1st (36-38) and 3rd (42-44) Presidents of Texas were (was) Sam Houston who had lived among the Indians, had had an Indian wife, spoke several Indian dialects (as did Neely Bryan who was 17 years younger but born in eastern Tennessee within a hundred miles of where Houston was living with the Cherokees) was very pro-Indian in policy. Lamar, the 2nd (39-41) President was totally opposite believing that the only good Indian was a dead one did everything he could to shove all Indians out of Texas or to exterminate them. In his first term, Houston had dispatched James Pinckney Henderson to Europe to gain recognition for Texas from all foreign countries especially England and France. In his first term, on 3/1/37, Texas had petitioned the US President and Congress for Annexation; but on 7/9/38, Congress adjourned without action so on 10/12/38, Texas withdrew the petition.

In his final term, Houston's key concerns were Foreign Affairs, Indian Relations, War with Mexico (who had occupied San Antonio again), and Annexation to the USA. He sent Henderson and Van Zandt as representatives to the US government especially for the subject of annexation. Given the above circumstances, it is easy to understand why for months he had sent messages to Indian friends proclaiming a "Grand Council" at Fort Bird at the full moon in August 1843. Months in advance, Houston sent Indian Commissioner Joseph C Eldridge out to bring the Comanches to the Fort Bird Grand Council. Eldridge received rough treatment and the Comanches did not show up. Houston treated Eldridge roughly for having failed to bring them in; but in later years, Houston made up for it by getting Eldridge appointed assistant paymaster in the US Navy where he served with several commands including Commodore Oliver Perry in opening up Japan and in expeditions for laying the Atlantic telegraph cable.

When Houston arrived at Ft. Bird in the Trinity River bottoms, several tribes showed up but did not want to go near the garrisoned fort fearing a trap. Houston moved the negotiations and camping six miles to Grapevine Springs possibly also due to fewer mosquitoes, better water, and better breeze with more large shade trees for protection from the summer heat. While at Grapevine Springs, in addition to negotiating with the Indians, he was still having to deal with Foreign Affairs, War with Mexico, and Annexation to the USA. In fact, before the treaty was signed, he had to go back to the Texas capitol leaving his Indian Commissioners to finish the job.

After several weeks back at the capitol, Houston sent his Annexation representatives a policy statement basically telling the US it had one shot at getting Texas as a state, now or never. That one Texas/USA Policy paper is worth going to that website to read. England and France had jointly undertaken to guarantee the protection of Texas from Mexico and any other country if Texas would just promise to not be annexed to the USA. If this policy statement was not developed while at Grapevine Springs, it certainly could not have been far from his mind the whole time. After the Bird Fort Treaty of Peace and Friendship was signed at Fort Bird on Sept. 29, 1843, Houston started motions toward a Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Commerce which was signed at Tehuacana Creek on Oct. 9, 1844. Eight tribes signed both treaties-Keechi, Waco, Caddo, Anadarko, Ioni, Delaware, Cherokee, and Tawakoni. Two tribes signed only the Bird's Fort Treaty-Chicasaw and Biloxi. Three tribes signed only the Tehuacana Creek Treaty; Comanche, Shawnee, and Lipan. Full texts of both treaties are on the web site mentioned above. While similar in format and verbiage in several areas, the details of the 22 articles of the Tehuacana Creek Treaty are substantially different than the details of the 24 articles of the Bird's Fort Treaty. Main difference is focus on Commerce on the later treaty. Also on the web site are letters authorizing gifts to be given to the Indians (especially the Comanches) to get their attendance.

Now, just suppose, that Lamar had not wanted to exterminate the Indians or Militia had not been sent out for that purpose, or Tarrant had not run into that lone Indian, or the villages along the creek had not been attacked, and Fort Bird had not been built? If Neely Bryan had indeed been too busy as an trader to spend any time planning an town; or if Mexico had killed or captured Houston before annexation and replaced the government with one of its own; or annexation itself had not taken place; what would Dallas be like today? Would thousands of Indians be living in Mid cities? Would Spanish be the predominant language? Maybe yes; maybe no; but certainly it would be different.

Photo provided by Gerald Harris

Bird's Fort Treaty

Site of Bird's Fort

Arlington (Tarrant Co.)

FM 157, 1 mi N. of Trinity River near Arlington

In an effort to attract settlers to the region and to provide protection from Indian raids, Gen. Edward H. Tarrant of the Republic of Texas Militia authorized Jonathan Bird to establish a settlement and military post in the area. Bird's Fort, built near a crescent-shaped lake one mile east in 1841, was the first attempt at Anglo-American colonization in present Tarrant County. The settlers, from the Red River area, suffered from hunger and Indian problems and soon returned home or joined other settlements.

In August 1843, troops of the Jacob Snively Expedition disbanded at the abandoned fort, which consisted of a few log structures. Organized to capture Mexican gold wagons on the Santa Fe Trail in retaliation for raids on San Antonio, the outfit had been disarmed by United States forces.

About the same time, negotiations began at the fort between Republic of Texas officials Gen. Tarrant and Gen. George W. Terrell and the leaders of nine Indian tribes. The meetings ended on September 29, 1843, with the signing of the Bird's Fort Treaty. Terms of the agreement called for an end to existing conflicts and the establishment of a line separating Indian lands from territory open for colonization.

Sam Houston

Photo from the book, The Men Who Wear The Star, by Charles M. Robinson,

III

Negotiations began at the fort between Republic of Texas officials Gen. Tarrant and Gen. George W. Terrell and the leaders of nine Indian tribes. The meetings ended on September 29, 1843, with the signing of the Bird's Fort Treaty. Terms of the agreement called for an end to existing conflicts and the establishment of a line separating Indian lands from territory open for colonization. Houston proposed commissioning three trading houses, one at the forks of the Trinity, a second at Comanche Peak and a third at the Old Mission on the San Saba River. He sent out agents to inform the chiefs of the tribes that he requested their presence at a powwow in the fall of 1843, at Bird's Fort. They were told he would distribute presents and negotiate terms of peace.

One party of agents, under Joseph C. Eldridge, located a Comanche camp where they were received by the wives of Chief Pa-hah-yuca, who was away on a hunt. After a week (during which the camp was moved twice), the chief returned and gathered a council of a hundred warriors to consider Eldridge's proposal. During the council, Eldridge and his party were held captive, but they could hear the warriors angry rejection as they recalled the fateful Council House Fight of 1840. For over a day it seemed to the captives that they would soon be tortured and murdered. Fortunately, Eldridge had brought a token of good will, two captive Comanche children. Their return swung the mood of the warriors to conciliation and the chief sent Eldridge and his group back to Bird's Fort with an agreement for a future meeting, the exact time to be arranged. When Eldridge returned, Houston had already left Bird's Fort. He had met on the 29th of September and signed a treaty with representatives of all the major tribes except the Wichita and the Comanche.

The terms included the understanding that from the forks of the Trinity on a line to the southwest to Menard, the western side would be red man's hunting ground, while the east would be the white man's farm land. Beyond the border was "Where the West Begins." Only authorized delegations, such as teachers, blacksmiths, and licensed traders, could cross into Indian territory. Trading posts would be built along the line; property belonging to one side found on the other side would be restored to its proper owner through post officials.

These ceremonies were the high point in the history of the fort. Captain Bird and his men found the fort uninhabitable soon after it was built four years earlier. A band of Indians burned the grass around the fort causing a lack of game and forage. Though it was reoccupied time and again, the winters and the Indians always proved too severe and more than a few lives were lost. Captain Johnson built his fort to the south about ten miles soon after the treaty was signed. Often referred to as Johnson's Station, it succeeded where Bird's Fort had not, providing pioneers with end of the trail necessities to settle their new homes and thrived until Statehood and the construction of Fort Worth which became the new western outpost.

Communities and Related Links

Bird's Fort Web Site

Home | Table of Contents | Forts | Road Trip Maps | Blood Trail Maps | Links | PX and Library | Contact Us | Mail Bag | Search | Intro | Upcoming Events | Reader's Road Trips Fort Tours Systems - Founded by Rick Steed |