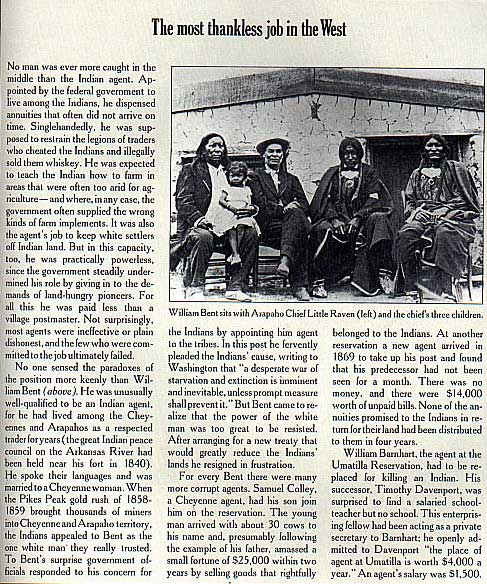

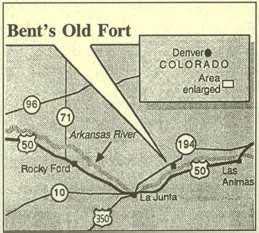

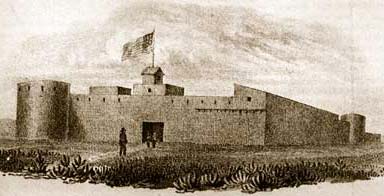

Decades before the nineteenth century, explorers, adventurers, hunters and trackers trekked across the Great Plains, the Rockies and beyond. Countless numbers married into various tribes and with the aid of their new in-laws, prospered at their endeavors. Some opened trading forts. Perhaps most famous was William Bent, who joined the Cheyennes, married the chief’s daughter and established his famous fort near the Santa Fe Trail.

The Comanches negotiated a peace with the Cheyenne in 1840 at a council held near the fort. Western migration had reached the Plains. Texas Rangers had badly weakened the Southern Comanche and the Northern bands found the displaced United States tribes a formidable foe who badly wanted to expand upon the Plains. All parties knew the powerful forces of the United States along with their land hungry settlers were coming. Six years later, the United States Army occupied Bent’s Fort. In the book, The Old West, The Indians, Benjamin Capps describes the Great Peace: The Comanches did not want to wage a two-front war. It had not taken the lords of the south plains long to make a decision; they told their friends the Kiowas to attempt a peace feeler toward the leaders of the Cheyenne-Arapaho alliance. The Comanches would let the Kiowas handle most of the ceremonies; they themselves would send only enough emissaries and gifts to make clear their agreement to the proceedings. In the Kiowa Nation one division, called the Kiowa-Apache, was noted for being friendly and peaceable. They sent up a delegation to an Arapaho camp headed by Chief Bull and told Bull that the southern tribes were prepared to consider peace. In the course of the meeting a raiding party of Cheyennes also stopped at the camp. They would not smoke with the Kiowas; as simple warriors they had not the authority to make this formal symbol of peaceful commitment. But they quit their raid and immediately turned back to carry the word to the Cheyenne chiefs. Within a matter of days the Cheyenne people had agreed and arranged a preliminary conference on the Arkansas River and some seventy miles east of Bent's Fort.

To this site came the Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs, led by High Backed Wolf, that old Cheyenne fighter and diplomat, who had consulted the most important warriors of his tribe and had been given authority to conclude peace. Two days later representatives of the southern alliance arrived: Kiowa Chiefs Little Mountain. Sitting Bear, Eagle Feather and others. All the leaders from both sides sat down in a line, and Eagle Feather, acting for the southern tribes, passed a lighted pipe. Each man solemnly took a puff. The ceremony meant that their hearts and minds were at one, and that their intentions were not in conflict. The next item of business concerned a mysterious bundle wrapped in a Navaho blanket. It had been brought to the conference by the Kiowas and, as tactfully as possible, Chief Eagle Feather revealed that it contained the scalps of the Bow String warriors. He offered to give them back to the Cheyennes. High Backed Wolf considered the matter, then said: "Friend, these things if shown and talked about will only make bad feeling. Do not let us see them or hear of them." The leaders from the south had also brought with them a youngster, a chief's son. Now, in gratitude for the initiative of the other side, the Cheyennes offered blankets as presents and threw them on the ground around the boy until all that could be seen of him was his head sticking up in the middle of the pile of gifts. Afterward they all feasted and planned a larger council for the final peacemaking. Kiowa Little Mountain asked the other side to choose a site for the big meeting, specifying that it must be a wide place for large camps and many horses. The Cheyennes chose a place upstream on this river, about six miles below Bent's Fort, where they frequently traded. The leaders of both sides left he preliminary conference with confidence that a good peace could be made. During the next two weeks messengers rode over the south and central plains informing the various bands of the time and place for the big council. The four major tribes involved spoke five distinct languages. Communication would be difficult, but not at all impossible. In the first place many of the tribesmen were multilingual. Nearly every leader spoke more than one language. From captives and from intermarriage in more peaceful times they had developed an abundance of competent interpreters. They had, in addition, the sign language in which all the plains tribes were proficient. With a few hundred signs, many varying in meaning according to context, and through ingenious combinations of these signs, an Indian could express thousands of thoughts from the simple device of pointing to himself for "I" or "me" to the complicated expression of the verb "to be." The latter idea was shown by the right hand clenched upright in front of the chest, then moved down a few inches, almost as if one were stamping a document, the motion firm and steady; it meant "to be" or "to remain" or "to sit." Undoubtedly those who spoke in signs learned to be especially attentive and sensitive to the intent and meaning of the persons before them. The main council gathered at the wide bottomland of the river; and any remaining tensions in the great encampment disappeared after the southern chiefs feasted in the special lodge. The chiefs smoked together, made speeches praising one another's worthiness and bravery, and feasted. The Cheyennes observed protocol in providing meat-no bear for the Kiowas, for it was taboo to them; no dog for the Comanches, for to them eating a dog was like eating one's own grandmother. The climax of the chief's meeting came when Kiowa Little Mountain rose to issue a long-awaited invitation: "Now, my friends, tomorrow morning I want you all, even the women and children, to cross over to our camp and sit in a long row. Let all come on foot; they will all return on horseback." The following day the northern Indians splashed across the stream and sat in long rows, expectant, with the men in front, then the women, then the children. The giveaway was an important institution. It was a form of conspicuous consumption showing the wealth of the giver and his careless disdain for property. But is also flowed out of real generosity and the desire to show goodwill. Most important, it showed insight into human psychology. People sometimes have differences that cannot be settled by rational dialogue or argument, but if one side presents a valuable and needed gift the differences may be wiped out as if by magic. To make the giving a solemn and orderly ceremony the Southerners presented small sticks as counters to those who sat in the long rows. The first to pass along was the slender Kiowa War Chief Sitting Bear, his left arm holding a great bundle of sticks, his black hair and long drooping mustache sparkling with grease. Four times in early manhood he had danced the exhausting sun dance for the good fortune of his tribe. Since then he had remained in the eyes of his people a man of grace and dignity, and now he had also become their most trusted war leader. He passed out his armload of sticks, then went to the bushes and broke off more to pass out; in all he gave two hundred fifty horses out of his own herd. During the distribution of the sticks the Kiowas and Comanches sent their boys and their Mexican slaves out into the hills to drive the horses into the flats where the camps stood. They drove in horses of every description and color, some flighty, some docile, and the beasts made a crowded melee among the tipis and cottonwood, the herders shouting to control them. The northern Indian flocked toward the donors who had given them sticks and had their particular gifts pointed out to them. Everyone old enough to ride got a least one mount; some got six or more. High Backed Wolf then invited all the southern people to come to his side of the river the following day. Over there, inside the big camp circle, the Cheyennes brought out exotic foods traded at the fort for the occasion: steaming kettles of rice and pots of dried cooked apples, how stews of meat and bone marrow, the gravy thickened with ground corn meal-and to sweeten the food, New Orleans molasses. When they had eaten, High Backed Wolf cried out to his people to bring presents. They brought brass kettles, beads, blankets, calico, guns. High Backed Wolf cautioned his guests that his warriors like to fire a gun into the air before giving it away. For a time the camp was in an uproar as the Cheyenne men fired the noisy muzzle-loaders; then they presented the guns, still warm and smoking, to the visitors. Thus they made peace. Some of the bands remained at the site several days to wade the river back and forth, to make new friends, to gamble and to continue with the round of other sports and games. The old griefs and hatreds were wiped out. Parties rode upstream to trade at the adobe fort. The Bents were pleased at the new customers, but refused to provide whiskey while so many former enemies were present. The four tribes never broke the peace made at the Arrowpoint, but their agreement amounted more to a nonaggression pact than to any organized coalition against the forces that threatened them all. The following October, having settled their problem of a two-front war, the Comanches staged the biggest raid they ever made into Texas. They pressed their attack through the white settlements all the way to Linnville on the Gulf Coast, and some frightened whites even put out to sea in boats to escape them. The raid was significant as a symbol of what lay in store; it seemed to be successful, and many horses and much plunder were gathered. But as the marauders retreated west the whites gathered their forces in pursuit, and the Texas militia struck a smashing blow at the invaders in the Battle of Plum Creek. It would always be a moot point as to who was the victor, but the clear lesson was that the Comanches could not teach the Texans a lesson. The peace of 1840 between the Indians of the south and central plains was a very humane accommodation to the immediate situation, yet the Indians of each tribe would face more in the future than they faced on this day. The fate of Sitting Bear, a noble savage if ever one existed, epitomized what was happening. In one of the most brave and defiant acts ever done by a man, he would die as a prisoner of the U.S. Cavalry thirty-one years later, literally forcing his captors to shoot him down. In his death he mutely testified to the inability of the Indians to guide the long sweep of Western history, but here on the Arrowpoint he had already made history of a kind. See him in the summer sun walking on the river sand before the rows of Indians, ceremonious, graceful, a demigod with lice. He had slain them generously, and now he gave them two hundred fifty precious horses. The harsh anti-Indian policies of President Mirabeau B. Lamar and Mexican efforts to weaken the Republic of Texas stirred Indian hostilities. Hatred increased after the Council House Fight in San Antonio, Therefore the Great Peace was made, setting the stage for the Battle of Plum Creek. Bent's Fort

|

||||

|

||||