|

In 1862, the Union Army was forced to deal with an uprising of the

Sioux in Minnesota and a similar situation involving the Apache and

Navajo in New Mexico. The responsibility for the latter fell upon the

old trailblazer, Kit Carson. As war wound down, Carson was sent to the

Southern Plains in search of raiders responsible for raiding along the

Santa Fe Trail in Kansas and Colorado. He found the offending warriors

but was nearly wiped out in the fight that followed. He was saved by

his cannon in what could well be the only situation history in the Indian

wars where artillery was the deciding factor.

Hwy. Marker-Battle of Adobe Walls: State Highway

15/FM 278,

five miles north of Stinnett.

On November 25, 1864; Largest Indian battle in Civil

War, 15 miles east, at ruins of Bent's old fort, on the Canadian. 3,000

Comanches and Kiowas, allies of the South, met 372 Federals under Col.

Kit Carson, famous scout and mountain man. Though Carson made a brilliant

defense-called greatest fight of his career-the Indians won.

Some of the same Indians lost in 1874 Battle of Adobe

Walls, though they outnumbered 700 to 29 the buffalo hunters whose victory

helped open the Panhandle to settlement.

The following story is from the book, Carbine & Lance, The Story

of Old Fort Sill, by Colonel W.S. Nye; Copyright © 1937 by the

University of Oklahoma Press. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

It was high time for another treaty. The Federals were not interested

in what was happening in Texas, but the outrages in Kansas and Colorado

aroused them to a war of reprisal. There was nobody on hand to make

a treaty; the military people were in charge in the West, and they

thought that the Indians ought to be disciplined rather than rewarded

for their forays. In Kansas the war schemes did not mature, as the

available troops were diverted in a vain attempt to catch the Confederate

raiders Quantrell and Shelby. In Colorado the government sent Colonel

J.M. Chivington, with the First Colorado Volunteer Cavalry, against

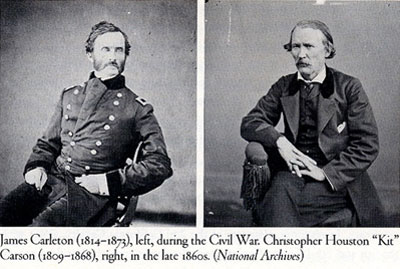

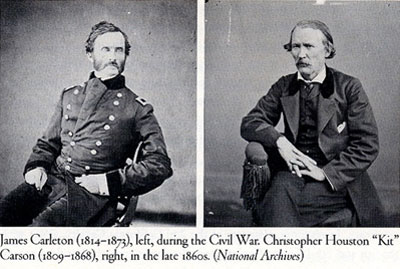

the Cheyennes. In New Mexico General J.H. Carleton sent Colonel Christopher

(Kit) Carson to attack the Kiowas and Comanches.

Carson's force consisted of three hundred volunteer cavalrymen and

a hundred Utes and Jicarilla Apaches. It was planned to strike the

hostiles in their winter camp, which was thought to be in Palo Duro

Canyon. Carson left Cimarron, New Mexico, on November 3, 1864. With

snow on the ground two feet deep, it was difficult for Carson to persuade

his Indian allies to make the march. When the weather is cold the

wild Indian loves nothing so much as the warmth of his lodge fire.

On November 24 the troops found the Kiowas and Comanches camped along

what is now called Kit Carson Creek in the Panhandle of Texas, near

Bent's old post of Adobe Walls. They attacked the upper part of the

village, killing several ancient braves, who, blind from the prevalent

trachoma, could not escape. Then they set to work destroying the camp.

To-hauson, great chief of the Kiowas-at that time an old man-galloped

downstream to warn the rest of the tribe. When he arrived, on his

steaming and blood-flecked horse, the women and children set up an

awful uproar of frightened wails. The warriors tied up their horses'

tails and galloped out to protect the camp. While they were riding

upstream the women and children fled in the opposite direction. The

white captive, Millie Durgan, was concealed in the brush but later

was rescued by her foster mother.

Hundreds of warriors arriving from the adjacent camps forced Carson

to abandon his attack and retreat. If he had not been covered by the

fire of Lieutenant Pettis' platoon of mountain howitzers he would

have been cut to pieces.

Kit Carson, "Crack Shot of the West."Photo from the book, Encyclopedia of American Indian Wars by Jerry Keenan.

The following story is from the book, Comanches, The Destruction

of a People, by T.R. Fehrenbach.

The respite given the Plains tribes by the Civil war was not enough

to allow them to rebuild their numbers. In the closing months of that

conflict, the United States military commands in the West were moving

swiftly to regain the initiative and effect a bloody retribution.

While the Colorado militia was mopping up the Amerindian villages

without regard to guilt or innocence in the wars, Colonel Kit Carson

of the New Mexico Territorials had crushed the Navajos. By the fall

of 1864, Carson's superior, the district commander General James H.

Carleton, was ready to turn the army's attention to the Comanches

and Kiowas, who all year had raised havoc along the Santa Fe Trail.

Angry bands of southern warriors threatened to cut completely this

route of communications with Missouri and the East. During 1864, virtually

every wagon train proceeding down the Canadian River to New Mexico

was attacked. Even large and powerful parties lost horses and oxen

to raiding Amerindians. Small groups, whether military or civilian,

had been massacred. In October, therefore, Carleton received orders

to restore full communications and to "punish the savages"

responsible for the depredations. He authorized Colonel Carson to

sweep through the valley of the Canadian with a strong force of New

Mexico and California territorials.

It was known that large numbers of Comanches and Kiowas were wintering

on the rich bison plains of the Texas Panhandle, and it was believed

that these Indians would not be prepared to fight a winter campaign.

Carson marched out of Cimarron, New Mexico, in early November with

more than three hundred mounted troops and seventy-two Ute and Jicarilla

Apache scouts and auxiliaries. The Utes were promised scalps and plunder,

and some warriors brought along their women. Carson was well supplied:

he had a well-stocked train of twenty-seven wagons and six thousand

rounds of ammunition. He was also furnished with two excellent little

twelve-pounder mountain howitzers, fitted on special traveling carriages.

The column followed Ute Creek to where it pours into the Canadian,

then rode east into the high Texas Plains along the broad, flat river

bottoms. The scouts went far ahead. At night, Carson camped among

tall cottonwoods in the gulches or cañadas. The weather was

already bitter, with snow flakes appearing. For days he saw no Indians.

Then, at sundown on November 24th, the scouts reported an encampment

about a day's march to the east, near the old, abandoned Bent and

St. Vrain trading post on a small tributary of the Canadian. This

place was known as Adobe Walls, from its still standing sun-dried

brick structures. Carson at once marched toward the Indians, pushing

his column through the frosty night for fifteen miles, allowing no

fires or smoking during rest breaks.

He was in sight of the Indian camp at daybreak. Lieutenant George

Pettis of the California volunteers, the officer in charge of the

two-gun battery, thought he saw gray-white Sibley tents in the distance.

Carson informed him that these were the sun-bleached tipis of Plains

Indians. The Utes reported a camp or village of 176 lodges. Without

scouting farther down the river valley, Carson detached his baggage

train with a guard of seventy-five men, and with a squadron of some

250 cavalry attacked across the two-mile-wide valley toward the village.

This was open country, surrounded by low hills or ridges, and covered

with dry grasses that rose horse-high in many places.

The Ute and Jicarilla auxiliaries left the column and tried to steal

the enemies' horse herd. The camp, which was Kiowa Apache, was alerted

before the cavalry reached it. The warriors formed a skirmish line

to cover the flight of their women and children, who abandoned the

tipis and ran for the ridges behind the river. The Plains-culture

Athapaskans, who were "Apache" only in dialect, often created

a confusion in accounts, which sometimes called them Kiowas, sometimes

merely Apaches. This led some whites to believe that there were still

Apaches on the Texas plains, and that they sometimes fought alongside

Nermernuh-the last unthinkable. The Kiowa Apaches formed an integral

part of the Kiowa tribal circle, and on this day one of the great

war chiefs of the Kiowas, Dohasan (To-hau-sen, Little Mountain, also

often called Sierrito), was in their lodges. Dohasan organized the

defense, while also sending for help from Comanche and Kiowa lodges

downstream. He rallied the warriors, and his swirling, shooting horsemen

slowed the white attack and assured the escape of the women. Carson's

cavalry killed one warrior who wore a coat of mail, but when they

reached the tipis they were deserted.

Dohasan exhibited great bravery. His horse was shot from under him,

but he was rescued and rallied his warriors. The cavalry pushed on

against the retreating Kiowa Apaches for about four miles, finally

reaching the crumbling Adobe Walls buildings. Here, more and more

Indians seemed to be appearing. The whites dismounted, and sheltering

their horses behind the trading post, began skirmishing on foot. Carson

came up to Adobe Walls with the battery, and now both the old mountain

man and the inexperienced Pettis saw another camp of some five hundred

lodges rising less than a mile way, along the river.

This was a Comanche encampment, and hundreds of warriors were streaming

from it across the prairie. Pettis counted "twelve or fourteen

hundred." The Indians formed a long line across the ridges, painting

their faces while their chiefs harangued them. The Kiowas, who were

also arriving in large numbers, roared he battle songs of their warrior

societies. Pettis feared that the horde would charge the white squadron

at any moment.

Carson ordered him to throw a few shells at the crowd of Indians.

The howitzers were unlimbered, wheeled around, and fired in rapid

succession. The shells, screaming over the warriors' heads and bursting

just beyond them, seemed to startle the Indians badly. Yelling, the

host moved precipitously out of range.

Carson told his troops that the battle was over. He ordered the horses

watered in Bent's Creek. The surgeon looked after several wounded

men while the others ate cold rations. However, the tall grass was

swarming with distance Comanches and Kiowas. Within the hour, a thousand

warriors surrounded the trading post, circling and firing from under

the horses' bellies. Surprisingly, most of the warriors appeared to

be equipped with good firearms. However, the twin cannon broke up

their attacks, and the exploding shells knocked down both men and

horses at a great distance. The enemy swirled about for several hours,

not daring to press too close, while the howitzers killed many on

the ridges. But Carson was becoming apprehensive. He had never seen

so many Indians. Pettis was sure that there were at least three thousand,

and small parties could be seen still arriving. The expedition had

marched unwittingly into a vast winter concentration of the tribes

on the southern bison range. Carson, with a split command, was worried

about his trains. His rear detachment, without cannon, would almost

certainly be overwhelmed if the enemy discovered it. He now made a

cautious but quite sensible decision: to break out of Adobe Walls

and regroup with his supply column, which had his food and ammunition.

The cavalry mounted and retreated behind the fires of the battery,

which stayed constantly in action. The Indians fired the grass, but

this helped, because the smoke concealed Carson's retiring column.

About sundown, the whites arrived back in the deserted Kiowa Apache

camp, where Pettis noted that the Ute women had mutilated the corpses

of several dead Indians. Carson ordered the lodges fired; then, under

the cover of darkness, he moved out rapidly to the west. The enemy

did not attack. Three hours later, he rejoined his wagons.

The next dawn, the Indians still held back. Some of the territorial

officers insisted that the expedition take up the attack, but Carson

ordered a withdrawal. The odds were much too great; Carson, who later

wrote that he had never seen Indians who fought with such dash and

courage until they were shaken by his artillery, did not make the

error of despising horse Indians. He had so far lost only a few dead,

and a handful of wounded, while his guns had inflicted serious losses,

killing and wounding perhaps two hundred Indians. He could claim a

victory, and did this when the column arrived back in new Mexico.

Carson's official report stated that he had "taught these Indians

a severe lesson," to be "more cautious about how they engage

a force of civilized troops."

Privately, he thought himself lucky to have extricated his command.

In fact, the howitzers and his own caution had probably saved him

from Custer's fate on the Little Big Horn. The Kiowas and Comanches

told some Comancheros who were in the Indian camps at the time that

except for the "guns that shot twice," the twin battery,

they would have killed every white man in the valley of the Canadian.

Carson himself said as much to Lieutenant Pettis.

Carson was angered by the presence of Comancheros with the Kiowas

and Comanches, which explained the source of the Indians' guns and

ammunition. He "had no doubt," he stated, "that the

very balls with which my men were killed and wounded were sold by

these Mexicans not ten days before." He wanted the New Mexicans

barred from trading with the wild tribes while the army was at war

with them. This was the beginning of what was to become a historic

hatred between the soldiers and the Comancheros.

Overall, the expedition had been less than completely successful,

and the white withdrawal left the Indians in full control of the territory.

Carson urged that the campaign be renewed, but with at least a thousand

troops, who, he thought, would destroy the Indian concentrations in

winter. The military authorities were planning extensive, determined

operations from Kansas to New Mexico when the sudden collapse of the

Confederacy changed everything again. The Comanches and other Plains

peoples were now to be granted their second stay within the decade.

The following story is from the book, Carbine & Lance, The Story

of Old Fort Sill by Colonel W.S. Nye.

On the Indian side To-hauson and Stumbling Bear were the heroes.

To-hauson had a horse shot under him. Stumbling Bear made so many

reckless charges that his small daughter's shawl, which he wore for

good luck, was pierced by a dozen bullets. Stumbling Bear was not

wounded. The battle ended with the troops retiring, closely followed

by the Indians, who set fire to the brown grass and harassed the soldiers

by shooting and charging from the cover of the smoke.

Colonel Chivington's campaign against the Cheyennes was more successful

than that of Carson. But it culminated in an affair so disgraceful

that it brought upon Chivington the condemnation of the entire country.

Black Kettle, a Cheyenne chief, had brought his village to Fort Lyon,

Colorado, in compliance with orders of the agent that all well-disposed

Indians should come in for roll call. While camped near the fort,

with an American flag flying over his tepee, Black Kettle was attacked

by Chivington. One hundred and twenty Indians were slaughtered. Women

and children were butchered in cruel and inhuman ways. A wave of horror

swept over the United States when the details of this attack became

known. The feelings of the Indians may well be imagined.

As a result of the Chivington massacre at Sand Creek, the hostility

of the Cheyennes and Arapahoes increased toward the whites, until

finally, in 1868, General Sheridan was forced to drive them to a reservation,

the eventual result of Sheridan's campaign being the establishment

of Fort Sill…

This last version is from the book, The West Texas Frontier, by Joseph Carroll McConnell.

During May of 1874, several buffalo hunters from Kansas and elsewhere, reached the Panhandle of Texas to pursue their chosen profession. The weather was delightful and the buffaloes were moving northward. To accommodate the hunters, two stores, a blacksmith shop, and a saloon were established not a great distance from the original Adobe Walls, built by the Bents many years before. This new location, also known as Adobe Walls was about one mile from the mouth of Bent Creek, and in a northerly direction from the present town of Miami.

Only about eight people lived at the post. But June 26, 1874, twenty-eight buffalo hunters, and one woman spent the night at this particular place. Some slept outside, and others within the temporary buildings. About two o'clock in the morning, Sheppard and Mike Welch, who were sleeping in Hanrahan's saloon, were awakened by an alarming sound. At first they thought, perhaps it was a gun, but soon discovered that a cottonwood ridge-pole, sustaining the dirt roof, was partly broken. In a short time, fifteen men were awake and helping repair the roof. By the time it was fixed, the eastern skies begun to present the first signs of day. Several of the buffalo hunters started to retire, but others preferred getting an early start, so they remained on their feet.

Although Jack Janes and Blue Billy had been murdered by Indians on the Salt Fork of Red River during the preceding day, it seems a majority of the buffalo hunters were unaware of impending danger.

But at least a small part of these frontiersmen had evidently received news during the preceding day that Indians intended to attack the Adobe Walls.

The warriors' hostility was most extreme because they fully realized the buffalo hunters were rapidly exterminating their main, and in fact, almost only source of supplies, the wild bison of the plains.

Billy Ogg went down to the creek, about one-fourth mile away, for the horses. A moment or two later, that well-known buffalo hunter, guide, and Indin scout, Billy Dixon, and others in the dim light, noticed a large body of objects advancing toward the Adobe Walls. A second later, he and they discovered these objects were Indians, who soon began to separate to make an attack. The breaking of the pole, perhaps, prevented the warriors from finding many of the buffalo hunters sound asleep and unprepared. Dixon ran for his gun and fired, and then hurried to Hanrahan's store, but found it closed. He hollowed to those inside to open the door. Bullets by this time were hailing all around. It seemed ages before the door opened. But finally Billy Dixon was admitted. About this time, Billy Ogg, who had gone after the horses, fell exhausted, near the door. He was hardly on the inside befor the Indians had the house surrounded. Two Shadler brothers, keeping in a wagon, were killed and scalped before realizing the Indians were around. About seven hundred feathered Comanches, Kiowas, Cheyennes, and other Indians, under the command of Quanah Parker, Lone Wolf, and other-noted chiefs were waging a most gruesome and bitter Indian war, as picturesque and spectacular as was ever fought in the Great West. Some of the buffalo hunters were undressed, but had no time to hunt clothes. In a short time the citizens organized, and about eleven men fortified in Myer and Leonard's store. About seven men and one woman, the wife of one of the buffalo hunters, found shelter in Rath and Wright's store. The others were in Hanrahan's saloon. During the first half-hour of fighting, the Indians struck the doors with the butts of their guns; but when they saw so many of their number dead on the ground, these tactics of war were abandoned. Many of the Indians dismounted and charged afoot. But when the feathered warriors began to fall, that particular mode of warfare was also abandoned. But again and again, the warriors charged.

The Indians had a bugler, and some of the men, who understood signals, stated that the horn was blown with as much accuracy as could be expected from an ordinary U.S. Army oficer. This bugler, however, was killed late in the evening.

About noon, the scouts in Hanrahan's saloon began to run short of ammunition. So Billy Dixon and Hanrahan ran to Rath's where there were stored thousands of rounds of ammunition, used in the long range buffalo guns. When Rath's store was reached, everything was found in good shape.

By two o'clock, the Indians had lost so heavily, they fell back and were firing at intervals from the hills. By this time, the red men had divided. A part were to the east, and the remainder to the west. But Indian warriors were riding more or less constantly from one group to the other. So the "Crack-shot" buffalo hunters turned their attention to them, and began to tumble these riders from their steeds. As a, consequence, in a short time, the savages were riding in a much wider circle.

About four o'clock p.m. and after the storm had passed, Burmuda Carlysle, ventured out to pick up some Indian trinkets. As he was not, fired upon, he went out a second time. In a short time, others followed, and it was then ascertained by all that Billy Tyler, at Leonard and Myer's store, had been killed at the beginning of the engagements.

The second day, only a few Indians were seen on a bluff across the valley. When the buffalo hunters fired, these Indians ran away but returned the fire before they left. All horses were killed and carried off.

Late in the evening of the second day George Bellfield arrived. When he saw a black flag flying, thought, at first, it was a joke. Shortly afterwards James and Bob Carter arrived. And late in the afternoon Henry Leath volunteered to go to Dodge City for help.

The third day, a party of about fifteen Indians again appeared on the bluff to the east of Adobe Walls. When Billy Dixon took deliberate aim at these warriors with his buffalo gun, the red men dashed out of sight. A few seconds later two Indians on foot appeared, and apparently took a wounded Indian away.

According to reports, the Indians' medicine men told them that on this occasion the savages would be practically invulnerable to bullets. But needless to say, they soon found the wrath of the gods against them.

There was a pet crow at the Adobe Walls at that time, and during the thickest of fighting from time to time, this mysterious bird flew from one building to another, Perhaps the presence of this peculiar bird was interpreted by the Indians as a sign the medicine en made a mistake.

Note: Author personally interviewed: Mrs. Billy Dixon. Mrs. Dixon wrote the book entitled, "The Life of Billy Dixon". Also interviewed A.M. Lasater, who several times heard Billy Dixon relate his experience; and others.

Further Ref.: An able account of this conflict written by R.C. Crane and published in the Fort Worth Star Telegram for Nov. 30th, 1934.

|